BEYOND THE NUMBERS

After decades of sharp increases in income inequality and dramatic tax cuts at the top, the case for reversing course and raising taxes at the top is overwhelming. That’s especially true given the sacrifices that policymakers will likely ask of Americans of modest means to help reduce long-term deficits. Below are three good first steps:

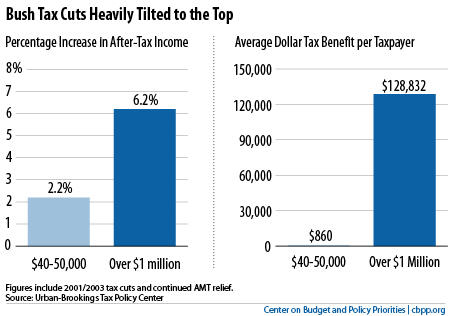

- Sunset the high-end Bush tax cuts. President Bush’s tax cuts are an obvious place to start. They were unaffordable from the start and are heavily tilted toward the nation’s richest people (see first graph).

Image

Letting the Bush tax cuts aimed exclusively at people making over $250,000 expire as scheduled at year-end — thus returning the top marginal rates to those during the Clinton years — would save about $968 billion over ten years. That would pose little risk to the economy, which did quite well under the Clinton rates. As the economic expansion continues and unemployment drops, we should phase out the rest of the Bush tax cuts as well. - Implement the Buffett Rule. The tax code should not be so easy to manipulate that millionaires can pay a smaller share of their income in federal taxes than middle-class people. But today’s tax code is: 21 percent of millionaires — about 50,000 people — pay a lower tax rate than 3 million people making between $50,000 and $100,000, according to the White House National Economic Council.

The Buffet Rule would ensure that people earning $1 million or more a year pay at least middle-class tax rates. By itself, it would raise only a small share of the extra revenue the country needs. But it would mark an important step in making the tax code fairer.

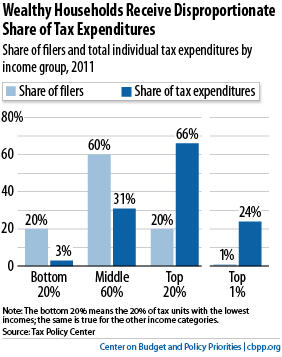

- Reform tax expenditures. Tax expenditures (tax credits, deductions, and other preferences) are expensive, costing $1.1 trillion in 2011. They’re also tilted towards the top of the income scale. The top 20 percent of tax filers received 66 percent of the benefits of tax expenditures that year (the top 1 percent alone received 24 percent of the benefits), while the bottom 20 percent of filers received only 3 percent of the benefits, according to the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center (see graph).Image

Moreover, many tax expenditures are “upside down”: they give the biggest benefits to high-income people, who are least likely to need a financial incentive to do whatever the tax incentive is designed to promote, like buy a home or save for retirement.

The home mortgage interest deduction is a prime example: high-income people in the 35 percent tax bracket save 35 cents in taxes for every dollar they pay in mortgage interest, while middle-income people in the 15 percent bracket save just 15 cents.

In addition to turning these tax expenditures right-side up, policymakers should reform one of the most top-heavy tax breaks: the current preferential tax rates for investment income, which are much lower than the rates for wage income.

In reforming tax expenditures, policymakers must use the resulting additional revenue to reduce deficits — not to regressively lower tax rates, as House Budget Committee Chairman Ryan’s plan would. As I said at the start of this series, all tax discussions need to keep our long-term deficit problem in mind.