BEYOND THE NUMBERS

When House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan unveils his budget plan this week, he almost certainly will again propose to convert Medicare into a “premium support” system, where beneficiaries would receive a voucher to buy private coverage or traditional Medicare. He may also repeat the frequent claim that the Medicare drug benefit’s lower-than-expected spending reflects efficiencies produced by competition among private insurers — and thus supports his proposal. So, while we showed in a 2012 report why this claim is incorrect, it’s worth doing so once again.

The Medicare Part D drug benefit, which private insurers deliver, did indeed cost much less over its first five years (2006-2010) than the Medicare trustees and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) originally expected. But, as a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis states, there “is compelling evidence that factors other than competition offer the best explanations for the lower-than-expected spending trend” in Part D.

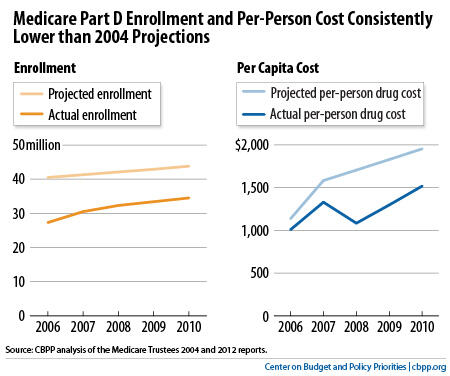

The biggest factor is lower-than-expected enrollment. The Medicare trustees found that actual average enrollment between 2006 and 2010 was 10.6 million — or 25 percent — lower than they had estimated when Congress enacted Part D (see chart).

This had a large impact on costs. Lower enrollment accounted for 51 percent of the difference between the trustees’ original cost projection and Part D’s actual costs over the first five years.

CBO data tell a similar story. Actual Part D enrollment for the period 2006-2010 was, on average, about 7.1 million (18 percent) less than CBO had expected. This lower enrollment accounted for 57 percent of the difference between CBO’s projected costs for Part D and the program’s actual costs between 2006 and 2010.

Part D costs per beneficiary were also lower than projected, but this mostly reflects a slowdown in per-capita prescription spending throughout the U.S. health care system. Actual Part D costs per beneficiary in 2010 were 22 percent lower than the Medicare trustees originally projected and 16 percent lower than CBO had estimated. But overall prescription drug spending per capita in 2010, as measured in the National Health Expenditures estimates, was 35 percent lower than the actuaries at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) projected when Congress enacted the drug benefit.

Drug spending growth declined unexpectedly — both in Medicare and throughout the U.S. health care system — because major drugs went off-patent, fewer costly new blockbuster drugs came to market, and use of lower-cost generic drugs increased substantially, according to the CMS Office of the Actuary (which helps prepare the Medicare trustees' reports and conducts the estimates of National Health Expenditures).

In fact, private plans actually raised Part D costs by doing a comparatively poor job of negotiating price discounts from drug manufacturers. When Congress created Part D, it assumed that private insurers would negotiate larger discounts than the ones Medicaid requires for the drugs it covers, but the opposite happened. The Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General found that the discounts negotiated by private Part D plans reduced the costs of the most widely used brand-name drugs by only 19 percent; in comparison, the rebates that Medicaid requires cut costs for those drugs by 45 percent.

CBO estimates that requiring drug companies to give Medicare the same discounts for drugs provided to low-income Part D beneficiaries that the Medicaid program receives, as the Administration has proposed, would reduce Medicare’s costs by $137 billion over ten years.