BEYOND THE NUMBERS

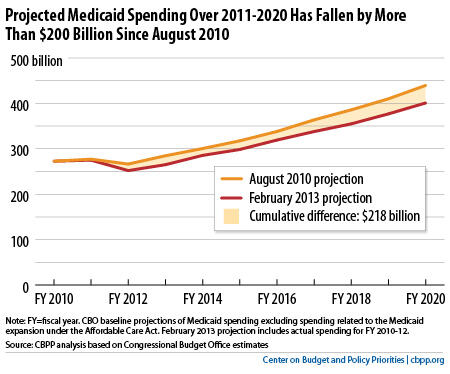

We’ve already noted that the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has reduced its projection of cumulative Medicare spending over the 2011-2020 period by more than $500 billion based on a comparison of CBO’s latest estimates with those of August 2010. The story’s basically the same for Medicaid: CBO similarly has reduced its estimate of projected federal spending on the program over the same years by about $218 billion, or 6.4 percent.

The chart below compares CBO’s projection of Medicaid spending from August 2010 with the projection that CBO released in February. We exclude spending related to the Medicaid expansion under health reform (including the effects of the Supreme Court decision upholding the Affordable Care Act) and focus on projected spending in the underlying Medicaid program.

The timing’s important because it was in late 2010 — and based on CBO’s August 2010 projections — when Fiscal Commission co-chairs Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson issued their original budget proposal, which called for slightly less than $60 billion in Medicaid savings through 2020. The original Simpson-Bowles proposal is often considered an appropriate starting point in evaluating whether other deficit-reduction proposals should be viewed as responsible approaches to the deficit problem.

CBO lowered its projections of Medicaid spending due to lower expected costs per beneficiary. It also now expects some lower-than-anticipated enrollment; for example, it now assumes fewer individuals will enroll in the Supplemental Security Income program and automatically become eligible for Medicaid.

Despite these positive trends, House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan almost certainly will again propose this week to convert the Medicaid program into a block grant. Rep. Ryan has claimed that a block grant is necessary because Medicaid is inefficient and its costs are out of control.

In fact, Medicaid is a lean program — it costs Medicaid substantially less than private insurance to cover people of similar health status. This is due primarily to Medicaid’s lower payment rates to providers and lower administrative costs. Moreover, the Office of the Actuary at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services projects that Medicaid spending per beneficiary (excluding the effects of the Medicaid expansion) will grow no more rapidly through 2021 than spending per beneficiary with private insurance.

We need to continue to increase the efficiency of the overall U.S. health care system, which in turn will improve our long-term fiscal outlook by further slowing the growth in Medicare and Medicaid. But like with Medicare, CBO’s latest projections show large declines in projected Medicaid spending. Medicaid’s modest spending growth thus does not justify radically restructuring the program by converting Medicaid to a block grant or establishing a per capita cap or instituting other deep Medicaid cuts that shift costs to states, beneficiaries, and health care providers.