BEYOND THE NUMBERS

This latest post in our breakdown of the Top Ten Facts About Social Security explains that benefit levels are modest, as are the changes needed to ensure the program’s long-term solvency.

Fact #4: Social Security benefits are modest.

Social Security benefits are much more modest than many people realize; the average Social Security retirement benefit in June 2015 was $1,335 a month, or a bit over $16,000 a year. (The average disabled worker and aged widow received slightly less.)

For someone who worked all of his or her adult life at average earnings and retires at age 65 in 2015, Social Security benefits replace about 40 percent of past earnings. This “replacement rate” will slip to about 36 percent for a medium earner retiring at 65 in the future, chiefly because the full retirement age, which has already risen to 66, will climb to 67 over the 2017-2022 period.

Moreover, most retirees enroll in Medicare’s Supplementary Medical Insurance (also known as Medicare Part B) and have Part B premiums deducted from their Social Security checks. As health care costs continue to outpace general inflation, those premiums will take a bigger bite out of their checks.

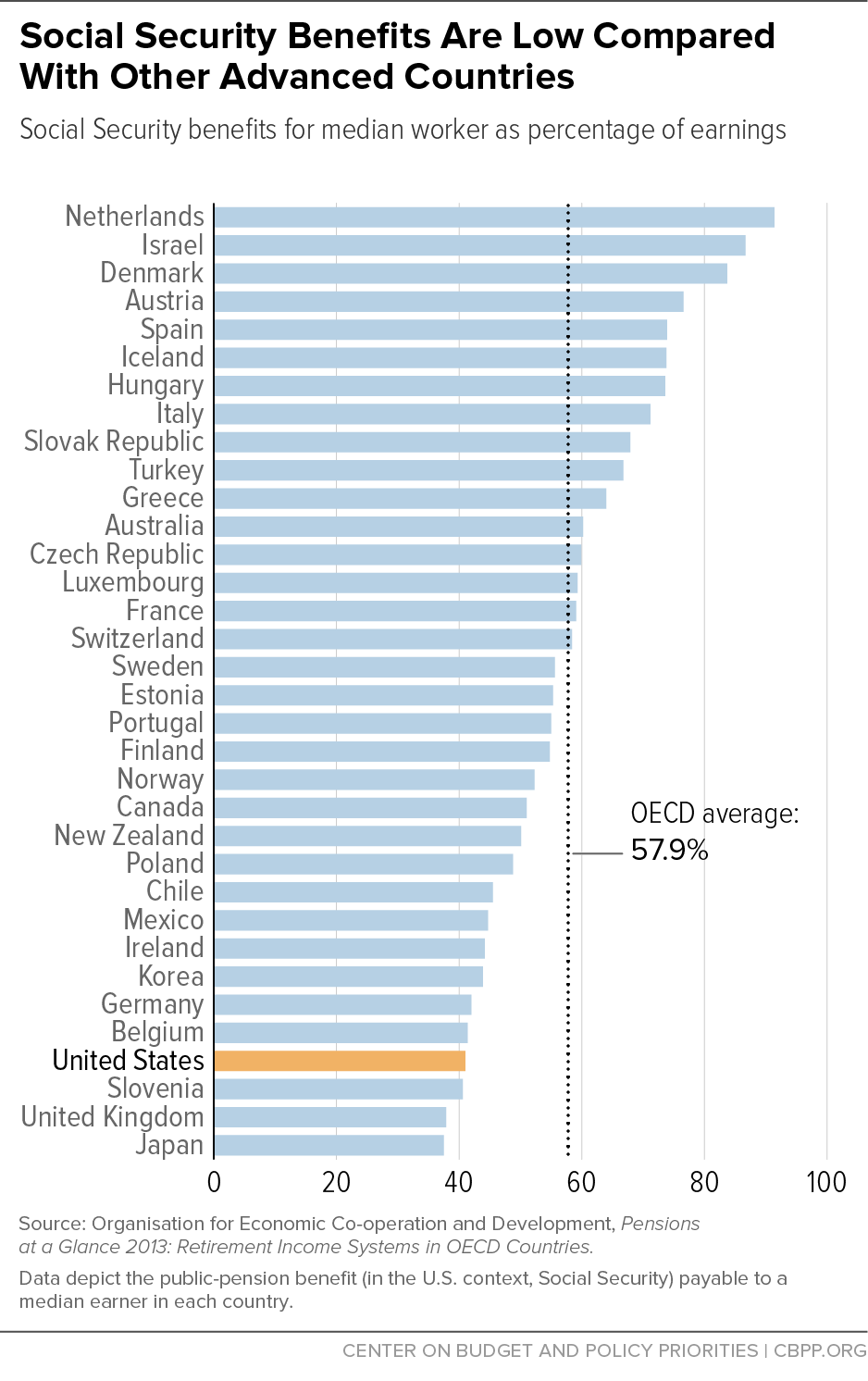

Social Security benefits are modest by international standards, too. The United States ranks 31st among 34 developed countries in the percentage of a median worker’s earnings that the public-pension system replaces.

Fact #10: Relatively modest changes would place Social Security on a sound financial footing for 75 years and beyond.

Since the mid-1980s, Social Security has collected more in taxes and other income each year than it pays out in benefits and has amassed combined trust funds of $2.8 trillion, invested in interest-bearing Treasury securities. But Social Security’s costs will grow in coming years as the large baby boom generation (those born between 1946 and 1964) moves into its retirement years.

By modestly shifting revenues between the program’s Disability Insurance (DI) and Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust funds, policymakers can enable Social Security to pay full benefits until 2034, the new trustees’ report shows. Reallocation is a traditional and noncontroversial step that’d free policymakers to focus on strengthening overall Social Security solvency for the long term. (Viewed separately, the DI trust fund faces exhaustion in 2016 and the much larger OASI fund in 2035.)

After 2034, even if policymakers took no further action, Social Security could still pay three-fourths of scheduled benefits, relying on Social Security taxes as they are collected. Alarmists who claim that Social Security won’t be around when today’s young workers retire either misunderstand or misrepresent the projections.

A mix of gradual tax increases and modest benefit reductions — carefully crafted to shield the neediest recipients and give ample notice to all participants — could put Social Security on a sound financial footing indefinitely. By enacting these changes, policymakers could reassure future generations that they, too, will be able to count on this popular and successful program.