BEYOND THE NUMBERS

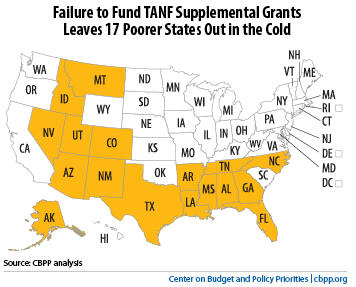

The bill that Congress passed last week to extend the payroll tax cut and federal emergency unemployment insurance also extended the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant through September 2012. But, in a continued unraveling of the deal that Congress made with the states in the 1996 welfare reform law, Congress provided no funding for the TANF Supplemental Grants, which 17 mostly poor states received every year between 1996 and 2011 (see map).

These grants were part of the original 1996 welfare reform agreement. Congress created them to address the fact that, under TANF’s funding structure, poor states receive less than half as much federal funding per poor child as other states.

Congress’s commitment to funding the Supplemental Grants started to slip last year when it funded them for only about two-thirds of the year; they ran out last July 1. When some members of the conference committee negotiating the payroll tax/unemployment insurance agreement sought to include funding for the grants in the bill, key Republican negotiators refused. (The committee included members from six of the 17 Supplemental Grant states: five represented by Republicans [Arizona, Georgia, Idaho, North Carolina, and Texas] and one represented by a Democrat [Montana]).

The end result is that the 17 states that have received Supplemental Grants for the last 15 years will receive significantly less federal TANF funding this year — $211 million less than last year and $319 million less than in earlier years.

Unlike some other issues that have stymied Congress in recent years, this one is not about money. Congress could have done what it did last year: pay for an extension of the Supplemental Grants by redirecting funds from another TANF fund, known as the Contingency Fund. Total federal funding for TANF would have remained unchanged.

The Contingency Fund is intended to help states during periods of economic distress. But, as we have noted, it is poorly designed and its funds are not well-targeted so they do not necessarily go to states with the greatest need.

By using a portion of the $612 million allocated for the Contingency Fund to fund the Supplemental Grants, Congress could have given the Supplemental Grant states money that they have relied on, while still leaving some money in the Contingency Fund for states that qualify for it.

To add insult to injury, much of the Contingency Fund money this year will go to states that already receive a substantial share of the TANF block grant and get much more TANF funding per poor child than the Supplemental Grant states. These states will receive more money this year than they received last year, while the Supplemental Grant states will get less.

New York is a case in point. With an unemployment rate of 8.0 percent (slightly below the national average), New York is poised to receive about $215 million from the Contingency Fund — about 35 percent of the total Contingency Funds available and more than all 17 Supplemental Grant states combined received in Supplemental Grant funds last year.

Meanwhile, the Supplemental Grant states are cutting services for some of their most vulnerable families. Florida, with an unemployment rate of 9.9 percent, is planning to cut its employment services for jobless workers. Georgia is reducing funding for child welfare services, child care assistance, and substance abuse services. Louisiana has entirely eliminated funding for Individual Development Accounts, which help low-income families build assets.

While there is no hope for getting funding for the Supplemental Grants this year, this issue — along with reforming how the Contingency Fund works — should be on the agenda when Congress renews TANF. When funds are limited, policymakers should make every effort to ensure that they go to the states and families that need them the most.