BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Senators Rand Paul (R-KY) and Barbara Boxer (D-CA) just proposed a “repatriation tax holiday,” which would allow U.S.-based multinational corporations to bring profits they hold overseas back to the United States at a temporary, vastly reduced tax rate. They claim it would not only “boost economic growth and create jobs” but also raise revenues to pay for extending the Highway Trust Fund. In reality, it wouldn’t do either.

A repatriation holiday enacted a decade ago proved a dismal economic failure. As our paper explains, a wide range of studies — by the National Bureau for Economic Research, Congressional Research Service, Treasury Department, and outside analysts — found no evidence that it produced any of the promised economic benefits, such as boosting jobs or domestic investment.

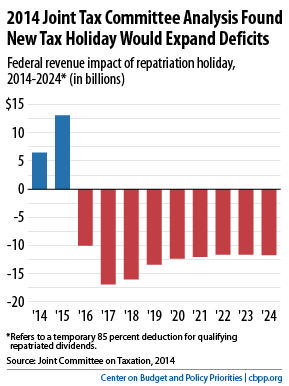

Moreover, a repatriation holiday would lose billions of dollars after the first two years, so it can’t “pay for” highway construction or anything else. A new repatriation holiday would lose $96 billion over 11 years, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated last year (see graph). The Paul-Boxer proposal has a somewhat higher “holiday” tax rate on those overseas profits than the one JCT analyzed (6.5 percent versus 5.25 percent) so it might lose less revenue. But it wouldn’t raise money. And it would make our long-term fiscal challenges harder.

A repatriation tax holiday would boost revenues in the first couple of years, as companies rushed to take advantage of the temporary low rate. But it would bleed revenues for years and decades after that. As JCT explained, the biggest reason is that a second holiday would encourage companies to shift more profits and investments overseas in anticipation of more tax holidays, thus avoiding taxes in the meantime:

A second repatriation holiday may be interpreted by firms as a signal that such holidays will become a regular part of the tax system, thereby increasing the incentives to retain earnings overseas rather than repatriating those earnings and to locate more income and investment overseas.

To be clear, a repatriation holiday is very different from a transition tax on overseas profits, such as the proposal from former House Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp. Any future corporate tax reform package would likely include a transition tax on existing foreign profits to clean the slate of existing tax liabilities. But a transition tax would be mandatory: multinationals would have to pay U.S. taxes on their foreign profits whether they repatriate them or not. By contrast, under a repatriation tax holiday, companies choose whether to repatriate their earnings, and the tax rate would be set extremely low to incentivize them to do so.

Also, a transition tax would be coupled with reforms to reduce or eliminate companies’ incentive to stockpile profits overseas — whereas another repatriation holiday would encourage firms to stockpile profits offshore, as noted above.

For these reasons, a well-designed transition tax — unlike a repatriation holiday — would reduce deficits, not raise them.