BEYOND THE NUMBERS

As they write final 2016 appropriations bills, policymakers will decide whether to include a proposal to sharply expand the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Moving to Work (MTW) demonstration with almost no reforms to address its shortcomings. As we’ve noted, policymakers should not expand MTW without significant reforms, including limits on state and local housing agencies’ ability to divert voucher funds from helping needy families rent housing.

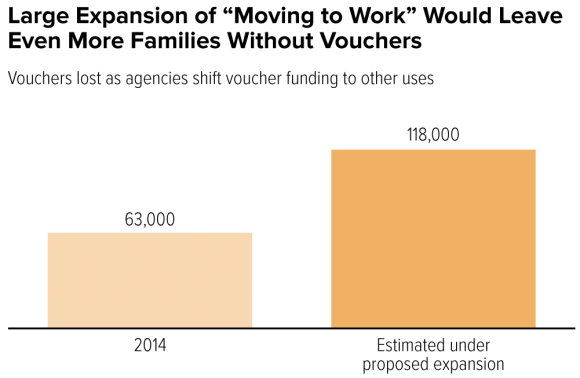

Currently, MTW allows 39 housing agencies to get broad waivers of federal rules governing the public housing and Housing Choice Voucher programs and to shift funds to other purposes. MTW agencies transferred close to a fifth of their voucher funds to other purposes in 2014, leaving 63,000 low-income families without vouchers (see chart). Nevertheless, some policymakers want to give more agencies the flexibility to shift voucher funds, in part to allow transfers to purposes that received inadequate federal funding in recent years, such as maintaining or renovating public housing and covering voucher program administrative costs. Policymakers should provide more adequate funding for these purposes.

But allowing more agencies to divert voucher funds by expanding MTW in its current form is the wrong way to address those needs. Here are three reasons why:

- Leaving families without vouchers exposes them to serious hardship. Vouchers sharply reduce overcrowding and housing instability and are by far the most effective way to cut homelessness among families with children. Vouchers can also allow families to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods, which raises children’s earnings and educational achievement later in life.

- Agencies have used some diverted voucher funds poorly. Most agencies have sought to allocate transferred funds to legitimate, potentially beneficial purposes, but some MTW agencies have reportedly paid unusually high staff salaries, accumulated large amounts of unspent voucher funds, and otherwise wasted or misused funds. Even when agencies target funds on public housing, they may use them for redevelopment projects that cut the number of units that poor families can afford. Overall, the number of public housing units at MTW agencies has dropped much faster than at non-MTW agencies.

-

Diverting voucher funds risks laying the groundwork for deep voucher cuts that would leave fewer total resources for low-income housing. If the number of agencies diverting voucher funds grew substantially, policymakers could reduce voucher funding and claim that agencies could implement the cuts by postponing redevelopment projects or scaling back administrative budgets, rather than by cutting rental assistance for vulnerable families.

The experience of other low-income programs that, like MTW, allocate federal funds as “block grants” that recipients — in this case, housing agencies — can use for a wide variety of purposes demonstrates the risk that this approach could lead to deep funding cuts. A new CBPP analysis finds that combined inflation-adjusted funding for the 13 major housing, health, and social services block grants fell by 27 percent from 2000 to 2015 — and housing block grants were among the hardest hit.

Policymakers shouldn’t expand MTW without also instituting reforms to ensure that the program doesn’t leave more vulnerable families without the help they need to afford housing.