BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Many school districts

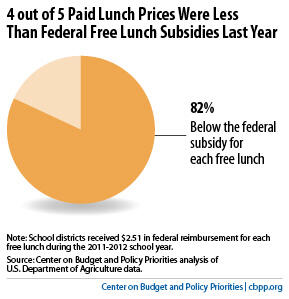

to cover the cost of “paid lunches” for students whose family incomes are too high to qualify for free or reduced-price lunches. As a result, some school districts divert part of the federal subsidies that are supposed to help pay for meals for low-income children to subsidize meals for better-off children, leaving less money to improve what’s on the plate. The most recent renewal of the school meals programs included a measured solution to this problem — but now some members of Congress mistakenly want to undo the fix.More than four-fifths of reported paid lunch prices in the contiguous United States were less than the $2.51 federal reimbursement that school districts received for each free lunch last year, according to Agriculture Department data (see graph). Not charging enough for paid meals creates a budget gap for school lunch programs.

When school districts don’t generate enough revenue to cover the cost of paid meals, they cannot serve the highest quality food, and funding for other priorities like food safety, electronic payment mechanisms that prevent low-income children from being stigmatized, and training and compensation for cafeteria staff may be jeopardized.

To address this problem, Congress in 2010 adopted a provision, known as paid lunch equity, to shore up revenues for paid lunches. School districts that generate less revenue for each paid lunch than for each free lunch must gradually close the gap between the two — by increasing non-federal revenue or raising prices by no more than five or ten cents per year. This provision will help ensure that the subsidies provided for low-income children go to their intended purpose — to feed our nation’s most vulnerable children.

Unfortunately, a bill introduced by Reps. Steve Stivers (R-OH) and Marcia Fudge (D-OH) would exempt most school districts from paid lunch equity. The bill’s supporters argue that a resulting price increase, amounting to no more than an extra $2 per month per child, would prevent or discourage many families from buying school meals. But undermining paid lunch equity would squander the opportunity to protect subsidies for low-income children. Plus, the case for the bill is extremely weak.

-

Participation in paid school meals fell this year, but there’s no evidence that prices played a role. Over the past three years, about 45 percent of children in the paid meal category ate a school lunch each day. A participation decline was widely expected because important new nutrition requirements kicked in this year, which may make lunches less appealing to some children until they adjust to the changes. In October 2012 (the most recent month for which this analysis is possible), shortly after the menu changes took effect, paid meal participation fell to 40 percent.

No research is yet available to sort out the extent to which menu changes are driving the decline versus the very modest price increases that result from the paid lunch equity provision, but it’s worth noting that school lunch participation has also fallen in many schools that serve all meals free (so prices are not a factor).

- The Agriculture Department (USDA) has already created an exemption. USDA plans to study the impact of paid lunch equity over the next year. Meanwhile, it created an exemption for the coming school year, which makes the Stivers-Fudge bill unnecessary. School districts operating exemplary programs that have substantial budget surpluses will not be subject to the paid lunch equity requirements.

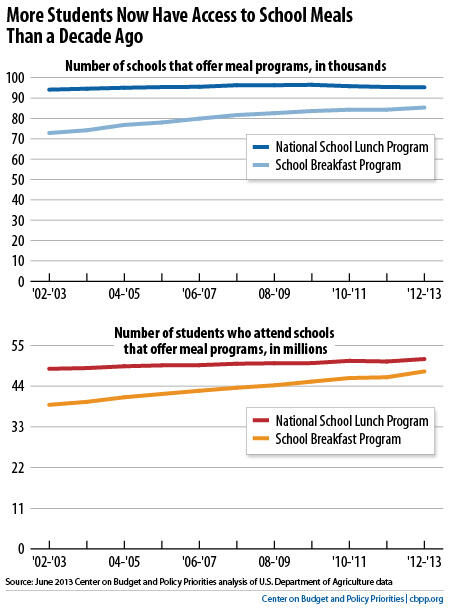

- Contrary to critics’ predictions, the requirement hasn’t undermined access to the school meals programs. Critics have argued that large numbers of schools would drop out of the National School Lunch Program rather than charge higher prices or make non-federal contributions to it. To the contrary, the number of schools offering lunch programs has basically held steady, and more children attend these schools and have access to the lunch program now than at any time in the last decade (see charts).

Until we know more about why participation has fallen and whether it is an enduring trend, Congress should not undo a very measured approach to shoring up the revenue of school food programs.