BEYOND THE NUMBERS

House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan (R-WI) will reportedly begin to release the details of his new budget proposal on Wednesday. House Republicans have already announced their goal is to balance the budget in ten years, and some have assumed this will require even deeper cuts and more extreme policies than last year’s Ryan budget, which did not balance after a decade. But this misses an important point: last year’s Ryan budget already required deep cuts and extreme policies of historic proportions.

As I wrote after Ryan released his budget last year:

The new Ryan budget is a remarkable document — one that, for most of the past half-century, would have been outside the bounds of mainstream discussion due to its extreme nature. In essence, this budget is Robin Hood in reverse — on steroids. It would likely produce the largest redistribution of income from the bottom to the top in modern U.S. history and likely increase poverty and inequality more than any other budget in recent times (and possibly in the nation’s history).

So, in assessing the budget that the Chairman will release this week, the issue is not whether it’s harsher than last year’s proposal but whether it continues to adhere to the same extreme approach that he has embraced in prior budgets.

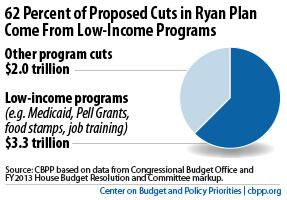

Here are some of the more disturbing aspects of last year’s budget:

- Radically restructured Medicaid by turning it into a block grant and slashing federal funding by more than one-third by 2022, as well as repealed health reform’s Medicaid expansion. All told, it would have added tens of millions of Americans to the ranks of the uninsured and underinsured.

- Cut SNAP (formerly known as food stamps) by over $130 billion; if the SNAP savings were achieved entirely through eligibility cuts, 8 to 10 million low-income people would have been knocked off the rolls.

- Sharply cut other low-income programs, such as Pell Grants, by tens or hundreds of billions of dollars. The budget documents showed that $758 billion in cuts would come from mandatory programs just in the income security portion of the budget, and the bulk of mandatory spending in that category goes for low-income programs.

Medicare. Ryan’s budget called for converting Medicare into a premium-support voucher program and gradually raising Medicare’s eligibility age from 65 to 67, with these changes ultimately affecting people now age 55 or younger. Raising the eligibility age to 67 while simultaneously repealing health reform’s coverage expansions would mean that 65- and 66-year-olds who could not get employer-based coverage would likely have to go without coverage, particularly if they were of modest means or had significant medical conditions.

Non-defense discretionary. The Ryan budget imposed severe cuts in non-defense discretionary programs, putting core government functions at risk. This part of the budget funds everything from veterans’ health care to medical and scientific research, highways, education, national parks, food safety, clean air and clean water enforcement, and border protection and other law enforcement; a significant portion of the funding goes for grants to state and local governments. Indeed, the budget would have cut these programs about $1.2 trillion over ten years beyond the tight annual caps set in the 2011 Budget Control Act. In fact, the Ryan budget would have cut non-defense discretionary spending substantially more than what would occur if the automatic budget cuts known as “sequestration” stay in effect for the full nine years.

What the Ryan budget did here essentially was to shield defense and shift the entire burden of the sequestration cuts onto non-defense programs. In fact, the Ryan budget went even farther than that: it increased defense funding by about $200 billion relative to the pre-sequestration caps and offset that increase with even deeper cuts in non-defense programs.

Tax cuts. The Ryan budget cut the top income and corporate tax rates to 25 percent, exempted from taxation the profits that U.S. corporations earn overseas, repealed the Alternative Minimum Tax, and repealed the tax increases in health reform, at a total cost of nearly $5 trillion. All of these revenue-losing measures would disproportionately benefit wealthy Americans. The budget claimed it would offset the costs of these massive, regressive tax cuts with other revenue-raising measures. But, while specifying its huge tax cuts, it did not contain a single specific proposal to narrow any particular tax break to offset even a fraction of these costs.

Chairman Ryan justified these changes in domestic programs last year as necessary because of the nation’s severe fiscal problems. But these problems surely do not justify massive new tax cuts for its wealthiest people alongside budget cuts that would fall disproportionately on less fortunate Americans.

As I concluded then:

Under Chairman Ryan’s budget, our nation would be a very different one — less fair and less generous, with an even wider gap between the very well-off and everyone else (especially between rich and poor) — and our society would be a coarser one.

That’s a yardstick that we should use in judging his new budget proposal.