BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Congress can redress a serious problem that it created last month by quickly enacting legislation, from Senators Jack Reed (D-RI) and Dean Heller (R-NV), to provide a retroactive three-month extension of the Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) program and using the time to craft a solution for the rest of the year.

When Congress failed the long-term unemployed by leaving for its holiday recess without renewing EUC, an estimated 1.3 million people who have been looking for work for over six months saw their unemployment insurance (UI) benefits end abruptly after Christmas week — and the economic recovery lost a valuable source of purchasing power.

As Congress considers whether to reverse course and enact the Reed-Heller proposal, here are some key points to keep in mind:

- EUC is a temporary program, but economic conditions have not yet improved enough to end it. EUC, like the federal emergency UI programs enacted in every major recession since the late 1950s, is a temporary program that provides additional weeks of UI to qualifying jobless workers during periods when jobs are hard to find. While labor market conditions are significantly better than in the depths of the Great Recession in 2008-09, they remain significantly worse than they were when policymakers ended previous programs. In particular:

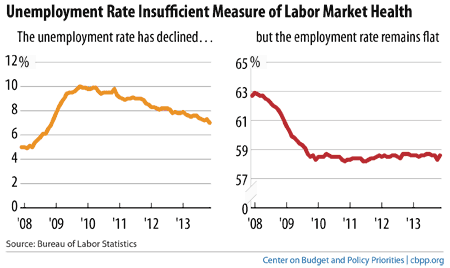

In a robust jobs recovery, the unemployment rate falls quickly and the share of the population with a job (the employment-population ratio, or employment rate) rises. Not this time, as these charts show.

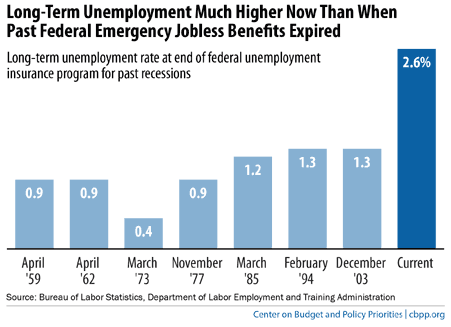

At 2.6 percent, the long-term unemployment rate is at least twice as high as when any of the emergency federal UI programs that policymakers enacted in each of the previous seven major recessions expired, as the chart below shows.Image Image

Image

- UI expenditures including EUC have been large but proportionate to the seriousness of long-term unemployment. EUC has lasted a lot longer, helped many more unemployed workers, and paid out substantially more in benefits than the programs enacted in past recessions. But that’s because the blow to the economy, and especially the labor market, from the Great Recession was so much worse. EUC has, in fact, been phasing down — the maximum number of weeks of EUC plus regular UI has fallen from 99 to 73, and that maximum is available in only a handful of states.

- UI may keep the official unemployment rate higher than it otherwise would be, but it has little effect on the employment rate. Economic research suggests that any disincentive for workers receiving UI to look for or accept a job has only a minor effect in elevating unemployment. At a time when there are still three unemployed workers per job opening, UI’s main effect on unemployment is to keep an unemployed worker in the labor force looking for a job — and therefore counted as unemployed in the official rate — rather than dropping out of the labor force entirely.

- UI is one of the most cost-effective measures for supporting spending in a weak economy. UI benefits go to people who need the financial assistance to make ends meet, they spend the funds quickly, and the spending ripples through the economy. In fact, without the consumer spending that UI generated, the recession would have been even deeper and the recovery even slower. And because EUC ends when the economy improves, it has only a minor effect on long-term budget deficits and debt. If policymakers decide they must fund a renewal of EUC with deficit-reduction measures, any such measures should take effect only after the economy is stronger because it would be counterproductive to have the deficit reduction take place at the same time. For example, Congress’s failure to renew EUC in the recent budget deal roughly offset the deal’s near-term stimulus effect.

A time will come when it is appropriate to end EUC, but it’s too soon to do it now.