BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Census Report Shows Rise in Full-Time Work, Undercutting Claims by Health Reform Opponents

Yesterday’s Census Bureau report shows that the share of workers with full-time, full-year work rose in 2013, while the share with part-time, part-year work fell. This finding further undercuts assertions that health reform is causing a large increase in part-time employment — as proponents of a House measure to change health reform’s rules on covering full-time workers claim.

Health reform requires employers with at least 50 full-time-equivalent workers to offer coverage to full-time employees — defined as those who work at least 30 hours a week — or pay a penalty. Critics claim that employers are shifting some employees to part-time work to avoid offering them health insurance. But the data provide scant evidence of such a shift.

To the contrary, part-time work became less frequent last year. “An estimated 72.7 percent of working men with earnings and 60.5 percent of working women with earnings worked full time, year round in 2013, both percentages higher than the 2012 estimates of 71.1 percent and 59.4 percent respectively,” according to the new Census report. These data are consistent with a recent Urban Institute analysis that found little evidence that health reform has increased part-time work.

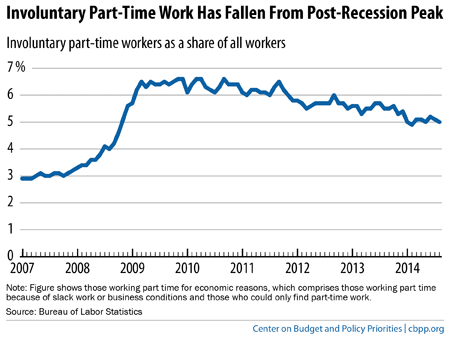

The share of involuntary part-timers — workers who’d rather have full-time jobs but can’t find them — tells a similar story. If health reform were distorting hiring practices, as critics assert, we’d expect the share of involuntary part-timers to be growing. Instead, as the chart (based on Labor Department data) shows, it’s down by 1½ percentage points from its post-recession peak. My colleague Jared Bernstein finds that this pattern is typical for this stage of a recovery.

Later this week, the House will consider a proposal (part of a so-called “jobs bill”) to raise health reform’s threshold for full-time work from 30 to 40 hours. But this step would make a shift toward part-time employment much more likely — not less so.

Only about 7 percent of employees work 30 to 34 hours (that is, at or modestly above health reform’s 30-hour threshold), but 44 percent of employees work 40 hours a week and thus would be vulnerable to cuts in their hours if the threshold rose to 40 hours. Employers could easily cut back large numbers of employees from 40 to 39 hours so they wouldn’t have to offer them health coverage.

If you exclude workers at firms that already offer health insurance and thus won’t be tempted to cut workers’ hours, more than twice as many workers would face a high risk of reduced hours under a 40-hour threshold than under the current 30-hour threshold, according to New York University economist Sherry Glied.

There’s little evidence to date that health reform has caused a shift to part-time work. There’s every reason to expect the impact to be small as a share of total employment, as we have explained. And raising the cutoff for the employer mandate from 30 to 40 hours a week would be a step in the wrong direction.