BEYOND THE NUMBERS

As recent comments from House Speaker John Boehner make clear, a central issue in debates over sequestration and other budget issues is whether higher revenues — on top of those in January’s “fiscal cliff” deal — will play any role in reducing deficits.

The revenues in that deal came mostly from raising tax rates on high-income households. Our new report explains why the next stage of deficit reduction should include major reforms to tax deductions, exclusions, and other tax breaks known collectively as “tax expenditures” and examines several specific proposals.

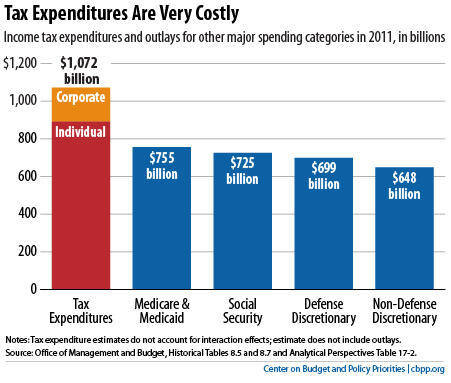

Tax expenditures are ripe for reform. They are very costly, totaling nearly $1.1 trillion in 2011 — more than Social Security or Medicare and Medicaid combined (see graph.) And many are “upside down,” meaning they give the biggest benefits to high-income taxpayers, who least need a financial incentive to do whatever the tax break is designed to promote (like buy a home or save for retirement).

Also, there is strong support on both sides of the aisle for reforming them. During the fiscal cliff talks, in fact, Speaker Boehner suggested raising $800 billion over the next decade — considerably more than the fiscal cliff deal will raise — by limiting tax expenditures.

Our report explores two complementary kinds of tax expenditure reforms:

- Setting an across-the-board limit. For example, the President proposes limiting the value of itemized deductions and certain other tax expenditures to 28 cents on the dollar. This proposal would retain tax incentives for desired activities like charitable giving. It would also reduce, though not eliminate, the “upside down” nature of some major tax expenditures by shrinking their value for high-income people.

- Closing tax breaks that allow wealthy people to avoid substantial tax. Some tax expenditures are embedded in the tax code in a way that would make it hard to touch them through an across-the-board limit. Policymakers should address them directly.

One example is the carried interest tax break, which allows investment fund managers to pay taxes on a large part of their income at the 20 percent capital gains tax rate rather than at normal income tax rates of up to 39.6 percent. As a result of this tax break, a hedge fund manager earning $10 million or more can pay a smaller share of his income in federal income taxes than a middle-income schoolteacher or policeman.

We’ll look more closely at these kinds of reforms in an upcoming post.

Policymakers should combine a well-designed tax-expenditure limit like the President’s 28-percent cap proposal with reforms of certain tax expenditures that wouldn’t be subject to the limit. In so doing, they could raise revenue as part of a balanced deficit-reduction package while making the tax code fairer and more efficient.