Revised April 21, 2003

NONCITIZENS’ USE OF

PUBLIC BENEFITS HAS DECLINED SINCE 1996:

RECENT REPORT PAINTS

MISLEADING PICTURE OF IMPACT OF ELIGIBILITY RESTRICTIONS ON IMMIGRANT

FAMILIES

By Leighton Ku,

Summary

| PDF of this report |

| If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

The 1996 welfare law made many legal noncitizens ineligible for certain public benefit programs, including Medicaid, Food Stamps, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI). There is substantial program data and research evidence showing that legal noncitizens’ participation in these programs has declined significantly since the law’s enactment. A recent Center for Immigration Studies (CIS) report, however, reaches a seemingly contrary conclusion, claiming that the “welfare use rates for immigrants and natives are essentially back to where they were in 1996 when welfare reform was passed.”[1]

This claim is striking, but misleading. In fact, the percentage of legal noncitizens participating in each of the major means-tested federal programs — Medicaid, Food Stamps, TANF, and SSI — has declined significantly since 1996.

The CIS report, which examines participation trends among what it calls “immigrant households,” itself finds that receipt of TANF, SSI, and food stamps by these households declined substantially between 1996 and 2001. But because it finds that the share of such households with at least one member who receives Medicaid rose modestly, CIS asserts that the share of immigrant households using “at least one major welfare program” has not declined since 1996.

CIS’ findings on Medicaid, as well, are

misleading. CIS fails to mention that the modest increase in Medicaid

participation by so-called “immigrant” households is due entirely to an

increase in Medicaid or State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP)

use by

Furthermore, analysis demonstrates that

U.S.-citizen children account for all of the increase in

Medicaid or SCHIP participation among

In other words, CIS’ claims that welfare use has failed to decline since 1996 — despite overwhelming data and research showing that the opposite is true — turns out to rest on the fact that the establishment of the SCHIP program led to an expansion in publicly-funded health insurance for low-income citizen children, a portion of whom live in households that include immigrant members.

What Census and Program Data Actually Show

Trends in participation by children and adults who are noncitizens (rather than citizens) provide a much more appropriate yardstick by which to measure the impact of the 1996 restrictions on noncitizens’ eligibility for public benefits. A new analysis of Census Bureau data (using the same database as CIS used) shows that among both noncitizen adults and noncitizen children, Medicaid participation declined between 1996 and 2001, a fact CIS inexcusably fails to disclose in its report.

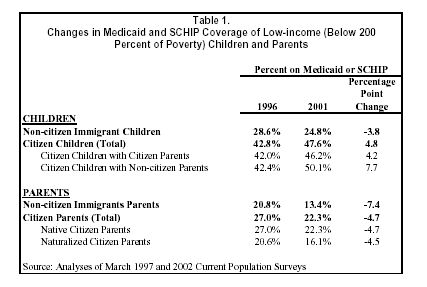

The percentage of low-income noncitizen children who participate in Medicaid or SCHIP fell from 28.6 percent in 1996 to 24.8 percent in 2001, despite the creation and expansion of SCHIP during this period;

During the same period, the percentage of U.S.-citizen children participating in these programs increased from 42.8 percent to 47.6 percent.

As a result, by 2001, low-income noncitizen children were only about half as likely to participate in Medicaid or SCHIP as U.S.-citizen children living in households with similar incomes.

Administrative data from other federal benefit programs show similar steep declines in non-citizens’ participation after the 1996 restrictions were put into place. For example, USDA administrative data show that participation by noncitizens in the Food Stamp Program declined 64 percent between 1996 and 2000, from about 1.7 million to 600,000. During the same time period, food stamp participation by all individuals declined by 30 percent, from 23.8 million to 16.7 million.

The CIS report purports to evaluate the effect of the benefit restrictions placed on many legal immigrants by the 1996 welfare law. In doing so, it uses a methodology that obscures the extent to which noncitizen participation has declined since 1996 in all of the major benefit programs, including Medicaid. As a result, the report paints a misleading picture that may leave policymakers and others with the mistaken impression that the benefit restrictions have had little impact on immigrant families. In fact, the opposite is true. Research using Census data has shown that food insecurity (defined as cutting back on meals or skipping meals involuntarily due to a lack of income, or having concerns that food will run out due to a lack of income) rose sharply among families headed by the immigrants most likely to be affected by the restrictions, and the percentage of noncitizens without health coverage increased in the late 1990s, primarily because of declines in Medicaid participation by noncitizens.

As part of welfare reauthorization later this year, Congress will consider proposals that would accord states some flexibility to restore Medicaid, SCHIP, and TANF benefits for certain legal noncitizens. Such proposals would help address growing gaps between citizen children and legal noncitizen children, and also enable states to elect to extend TANF-funded employment services and English-language instruction to unemployed legal noncitizen parents who may need such services or to working poor legal noncitizen parents who need such services to improve their job skills. Data on noncitizens’ use of benefits is likely to be part of this debate. As the debate moves forward, it should be informed by accurate information about the impact of the current restrictions on immigrant families.

It should be noted that CIS evidently seeks to

use its conclusions to advocate for more stringent restrictions on who is

allowed to enter the

CIS Methodology Obscures Extent to Which Benefit Use by Noncitizens Has Declined Since 1996

Several studies conducted in the last few years have found that noncitizens’ participation in means-tested public benefit programs has declined since passage of the 1996 welfare law.[3] For example, in a paper published by the Brookings Institution last year, Michael Fix of the Urban Institute and Ron Haskins, a former Senior Policy Advisor to President Bush on welfare issues (and now at Brookings), conclude that the noncitizen eligibility restrictions in the 1996 law have led to very large reductions in the receipt of benefits by noncitizens and that the reductions extend even to U.S.-citizen children of noncitizen parents.[4] The CIS report is the only piece of research to report increases in immigrants’ use of public benefits.

Unlike these other studies, CIS uses a methodology that is not well-suited to understanding the impact of the noncitizen eligibility restrictions. There are two general problems with the CIS methodology.

By focusing solely on trends in participation among households headed by foreign-born persons — without regard to the citizenship status of either the household head or those household members who actually receive benefits — the CIS report distorts the extent to which program participation has declined among noncitizens.

For example, consider a family with one U.S.-citizen parent, one noncitizen parent, and one or more U.S.-citizen children. (Among “immigrant” households, this configuration is fairly common.)[7] This family would be categorized as an immigrant family by CIS if the parent surveyed by the Census Bureau was the noncitizen parent, even though the family includes only one noncitizen member. If the noncitizen lost eligibility for Medicaid as a result of the noncitizen eligibility restrictions but the U.S.-citizen child continued to receive Medicaid, the methodology used by CIS would show no impact on participation by immigrant households in Medicaid. As another example, if a naturalized citizen marries a U.S.-born parent who already has a U.S.-born child, the household will be classified by the CIS as an immigrant household if the naturalized citizen is the individual in the household who the Census Bureau surveyed.

Despite using a methodology that understates declines in participation by noncitizens, CIS itself finds that participation by so-called “immigrant households” in the programs most commonly viewed as welfare (TANF/general assistance and SSI) has fallen substantially since 1996. For example, the CIS report shows that the share of immigrant-headed households with one or more members receiving TANF or general assistance fell by 60 percent between 1996 and 2001, from 5.7 percent of such households in 1996 to only 2.3 percent in 2001.[8] Similarly, the percentage of immigrant-headed households with one or more members receiving food stamps fell by 44 percent over the same time period, from 10.1 percent in 1996 to 5.7 percent by 2001.[9]

Despite these declines in participation in cash welfare programs and the Food Stamp Program, CIS still concludes that “welfare” use by immigrant-headed households has not declined since 1996, because 22.7 percent of immigrant households used “at least one major welfare program” in 2001, as compared to 21.9 percent of such households in 1996.

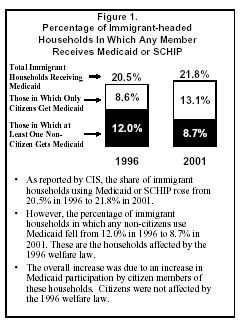

As CIS acknowledges, this trend is entirely explained by participation trends in Medicaid and SCHIP.[10] CIS reports that participation by members of immigrant-headed households rose slightly in Medicaid\SCHIP, from 20.5 percent to 21.8 percent. Medicaid participation — among both citizen-headed households and noncitizen-headed households — is significantly higher than participation in cash welfare programs or the Food Stamp Program. This is primarily because Medicaid has significantly higher income eligibility standards for children than these other programs. [11] Thus, CIS’ composite measure of “welfare” use, which reflects participation in any of the four programs, purports to show no decline in “welfare” use despite the large and unprecedented declines (even under CIS’ own faulty measure) in the percentage of “immigrant households” receiving cash welfare assistance or food stamps.

Modest Increase in Medicaid Participation

by “Immigrant” Households Entirely Due to Increase in Number of

Even though it is clear that there have been significant declines in cash welfare and food stamp use by immigrant-headed households, some may contend that the lack of decline in Medicaid use by such households is evidence that the restrictions have not reduced welfare use by noncitizens. This, however, is not the case.

The increase CIS finds in Medicaid participation

among “immigrant” households is entirely due to an increase in the number of

The 1996 welfare law maintained coverage for

Table 1 summarizes the results from a new

analysis of Census Bureau data (using the same data that CIS used) that we

conducted using a methodology that provides a much more accurate assessment

of the impact of the 1996 restrictions on noncitizen participation in

Medicaid and SCHIP. This analysis differs in three significant ways from

the CIS analysis. First, it examines participation by individual adults and

children rather than households heads. As noted above, CIS’ household level

analysis is problematic because it fails to distinguish between benefit use

by

As Table 1 shows, Medicaid participation among both noncitizen children and noncitizen parents declined sharply between 1996 and 2001.

It is not surprising that Medicaid participation

by U.S.-citizen children increased between 1996 and 2001. Coverage for

low-income children expanded substantially during this time period, largely

as a result of the creation of SCHIP in 1997.

In addition, the establishment of SCHIP spurred state campaigns to educate low-income working families about the availability of health care coverage for their children and to simplify application procedures. In many parts of the country, state and local officials conducted targeted outreach campaigns designed to increase enrollment among children in Latino families (some outreach campaigns also targeted children in Asian families). These targeted outreach efforts were undertaken in part because of data showing that Latino children were much more likely to be uninsured than other children in the United States.[13] Given these outreach efforts, it is not surprising that Medicaid use rose among U.S.-citizen children living in households headed by foreign-born persons, just as it rose more generally among all U.S.-citizen children.

|

Noncitizen Eligibility Restrictions Have Resulted in Increased Hardship Low-income immigrants have extremely high levels of participation in the labor force — a fact the CIS report correctly notes — but the jobs held by many immigrants pay low wages, provide few benefits, and can be unstable. As a result, immigrants are not immune from the hardships that other low-income working Americans can face, including lack of health insurance and difficulties affording food and housing.[1] The 1996 welfare law shows it is possible to reduce public benefit use by noncitizens who are lawfully admitted to the United States. These reductions have led, however, to increased hardship for many of these individuals. There is now strong research evidence that the noncitizen eligibility restrictions have such effects. George Borjas, a Harvard University economist whose work on immigrant participation in public benefit programs has been frequently cited by proponents of noncitizen eligibility restrictions, has documented a sharp rise in food insecurity (defined as cutting back on the size of meals or skipping meals involuntarily due to a lack of income, or having concerns that food will run out due to a lack of income) among legal immigrant families that are most likely to be affected by the eligibility bars that apply to many recently arrived non-citizens.[2] Other studies have shown that the proportion of noncitizen immigrants that have no health insurance increased after the welfare law’s immigrant restrictions were implemented in Medicaid.[3] In many other respects, trends in immigrants’ economic opportunities and status mirror trends in these areas for the general U.S. population. When the economy is stronger, both groups fare better. For example, the share of immigrants with incomes below the poverty line fell from 21.0 percent in 1996 to 15.7 percent in 2000, paralleling changes in the poverty rate for native citizens. But as the economy weakened in 2001, the immigrant poverty rate leveled off at 16.1 percent. Ultimately, immigrants are vulnerable to the same problems of poverty and unemployment as native citizens. 1 See, e.g., Jane Reardon-Anderson, et al., The Health and Well-Being of Children in Immigrant Families, Urban Institute, Nov. 2002; Randy Capps, et al. How Are Immigrants Faring After Welfare Reform? Urban Institute, Mar. 2002, Randy Capps, Hardship Among Children of Immigrants: Findings From the 1999 National Survey of American Families, Urban Institute, Feb. 2001. 2 George Borjas, Food Insecurity and Public Assistance, National Bureau for Economic Research, Sept. 2002. 3 Ku and Blaney, op cit. Brown, et al. op cit. |

Some may argue that the decrease in Medicaid use by non-citizens and the increase in Medicaid use among U.S.-citizen children in immigrant families both are due to increases in naturalization rates among legal noncitizens made ineligible for benefits by the restrictions in the welfare law. Other research has shown, however, that this is not the case. [14] Analysis by researchers at the Urban Institute shows that the percentage of naturalized citizens who receive public benefits remains relatively modest and increases in naturalization that occurred during the 1990s account for only a small fraction of the decline in benefit use among legal noncitizens. Similarly, our own analysis of the Census data shows that increases in Medicaid participation by naturalized children account for less than one-twentieth of the increase in Medicaid participation between 1996 and 2001 among low-income citizen children in households headed by a foreign-born individual.

Low Income Noncitizens Less Likely to Get

Benefits than Low Income

CIS also asserts that welfare use by

immigrant households remains much higher than that of natives and that

welfare “simply appears more attractive to immigrant households than to

native households.”[15]

CIS reaches this conclusion, however, only by failing to take into account

differing income and poverty levels between citizens and noncitizens. Noncitizens

have lower income levels overall than

Analyses by other researchers have demonstrated that this is not the case in TANF and the Food Stamp Program. For example, a recent study, commissioned by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, found that noncitizens who were eligible for the Food Stamp Program were significantly less likely to receive food stamps than all individuals who were eligible for the program; some 45 percent of eligible noncitizens received food stamps in 2002, compared to 59 percent of eligible individuals overall.[16] Analyses by the Urban Institute and others have similarly found that low-income noncitizens are less likely to get public benefits than low-income, native-born citizens.[17]

For example, as the data in Table 1 show, low-income noncitizens are much less likely to participate in Medicaid or SCHIP than low-income citizens. The disparities are striking — in 2001, some 42.6 percent of low-income citizen children participated in Medicaid or SCHIP, compared to only 24.8 percent of low-income noncitizen children. Moreover, this disparity increased substantially between 1996 and 2001. In 1996, there was a 14.2 percentage-point gap between the percentage of low-income citizen children participating in Medicaid or SCHIP and the percentage of low-income noncitizen children participating. By 2001, this gap had increased to 22.8 percentage points.

CIS Findings on “Average Value” of Benefits Received by Immigrant Households

CRS claims that the “average value” of welfare benefits that “immigrant households” receive did not decline significantly between 1996 and 2001. Like so many other claims in the CIS paper, this “finding” is based on misuse of data.

CIS acknowledges that the average value of most benefits received by immigrant-headed households — TANF/general assistance, food stamps, and SSI — fell substantially between 1996 and 2001. For example, the average annual value of food stamp benefits received by immigrant-headed households fell from $216 in 1996 to $104 in 2001. But CIS claims that the decline in the value of TANF, food stamps, and SSI benefits received by immigrants has been offset almost entirely by increases in average Medicaid benefits for immigrant-headed households.

An examination of the CIS figures that purport to show significant increases in the average value of Medicaid benefits that immigrant households receive shows, however, that these figures are highly problematic.

For these various reasons, CIS’ contention that average benefits for immigrant households did not change significantly between 1996 and 2001 is invalid.

Do Undocumented Immigrants Receive Public Benefits?

The CIS report includes data

on program participation by households headed by undocumented immigrants.

Undocumented immigrants, as CIS correctly notes, are ineligible for

Medicaid (except in certain emergency situations), SSI, food stamps, and

TANF. Households with undocumented immigrant in them may, however, have

This point is often misunderstood. For example,

in a recent press story on the Food Stamp Program in

While it is possible that some undocumented individuals may receive food stamps either because of errors made by eligibility workers or fraud, there is no evidence that erroneous receipt of food stamps by undocumented persons is a significant problem. The immigration status of all noncitizen applicants for public benefit programs such as Food Stamps and Medicaid is verified, pursuant to guidelines promulgated by the Attorney General, to prevent participation by ineligible applicants. Immigrants generally must provide documentation of their immigration status before they can be certified to receive benefits. These documents are then checked against an Immigration and Naturalization Service database to prevent undocumented and other ineligible immigrants from obtaining benefits.

It also should be noted that the procedure that CIS and other researchers use to identify undocumented immigrants in Census surveys may not accurately capture the immigration status of immigrants. The individuals surveyed by the Census Bureau are not asked whether they are legal or undocumented immigrants. Instead, analysts impute legal status to individual noncitizens using a variety of characteristics, including country of origin, age, receipt of public benefits and gender. There is no easy way to verify the accuracy of these imputations, which are somewhat controversial.

Conclusion

The CIS report does not recommend further restrictions on legal immigrants’ eligibility for public benefits. In fact, the report explicitly states that “immigrants … typically pay taxes from moment they arrive, so they should be able to access the programs that they need.”[21] Unfortunately, the report paints a misleading picture of trends in noncitizens’ participation in public benefit programs. Misleading statements in the report may be used to argue that further incremental restorations of benefits are not necessary or that further restrictions are needed because immigrants continue to receive “too much” welfare despite the 1996 restrictions.

The CIS report does not support such conclusions. Like other research, the report finds that receipt of TANF, SSI, and food stamps by immigrant-headed households declined substantially between 1996 and 2001. And while CIS asserts that the share of immigrant households with at least one member who receives Medicaid rose modestly, the increase is due entirely to an increase in the number of U.S.-citizen children participating in Medicaid or the State Children’s Health Insurance Program who live in households headed by foreign-born persons, some of whom themselves are naturalized citizens.

This is not the first time that CIS has been

faulted for reaching invalid conclusions because of poor research

methodology. In 2001, the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured

and the Urban Institute released a report refuting claims by the Center for

Immigration Studies that recent immigrants were responsible for most of the

growth in the number of uninsured people.[22]

That more careful analysis showed recent immigrants accounted for only a

negligible change in the number of uninsured people and that most of the

increase occurred among

Contrary to the findings touted in CIS press releases, the use of public benefits programs — including TANF, food stamps, SSI and Medicaid — has fallen among noncitizen immigrants since the 1996 welfare law was passed. By 2001, low-income noncitizen children were only about half as likely to participate in Medicaid or SCHIP as low-income citizen children.

Last year, President Bush proposed, and Congress

approved on a bipartisan basis, a restoration of food stamp benefits for

some legal immigrants. One of the bases for this restoration was that the

eligibility restrictions enacted in 1996 had substantially reduced food

stamp participation by legal noncitizen families (including many

If enacted, a restoration of Medicaid and SCHIP benefits could help to address the growing gaps in Medicaid participation — and in the proportion of the population that is uninsured — between legal immigrant children and citizen children. A TANF restoration would enable states to choose to provide TANF-funded employment-related work services and English-language instruction to jobless parents who may need such services to find jobs and to working-poor parents who may need such services to strengthen their jobs skills and become more productive employees. In any event, debates over these and other related matters need to be informed by accurate information and analysis that does not suffer from the numerous problems the CIS report exhibits.

End Notes:

[1] Steven Camarota, Back Where We Started: An Examination of Trends in Immigrant Welfare Use Since Welfare Reform, Center for Immigration Studies, March 2003, page 5.

[2] CIS Report at page 17.

[3]

See, e.g., Michael Fix and Jeff Passel, The Scope and Impact of

Welfare Reform's Immigrant Provisions, Urban Institute, Jan. 2002;

George Borjas, Food Insecurity and Public Assistance, National

Bureau for Economic Research, Sept. 2002; Leighton Ku and Sheetal Matani,

“Left Out:

[4] Michael Fix and Ron Haskins, Welfare Benefits for Noncitizens, Brookings Institution, February 2002.

[5]

The eligibility of legal noncitizens for public benefits varies among

federal programs and depends on a variety of factors, including date of

entry into the

[6]

Wendy Zimmermann and

[7]

According to the Urban Institute, a larger share of so-called

mixed-status families (families in which one or more parents is a

noncitizen and one or more children is a citizen) are made up of a

U.S.-citizen parent and a noncitizen parent (41 percent) than of two

noncitizen parents (39 percent).

[8] CIS report at page 6.

[9]

The decline in food stamp participation is likely due to declines in

participation among both noncitizens and eligible

[10] Although the CIS report refers only to Medicaid participation, the measures of Medicaid participation used by CIS include children participating in SCHIP.

[11] In many states, children remain eligible for benefits if they live in families with income up to 200 percent of poverty; by contrast, households with income over 130 percent of poverty are generally ineligible for food stamps, and the typical TANF income eligibility limit is nearly half that amount.

[12] In this analysis, noncitizens include both legal and undocumented immigrants.

[13]

In a recent example of such efforts, HHS Secretary Tommy Thompson stated

in a March 2003 press release that “Hispanics

continue to face health disparities. This is unacceptable,” and

announced the creation by HHS of a bi-lingual helpline designed to

provide Latinos with health care information

and refer them to SCHIP. “Secretary Thompson Announces the Creation of

a Bi-lingual Help Line, ‘Su Familia,’” HHS Press Office,

[14] See Michael Fix and Jeffrey Passel, The Scope and Impact of Welfare Reform’s Immigrant Provisions, Urban Institute, January 2002, pages 29-31; Kelly Stamper Balistreri and Jennifer Van Hook, The More Things Change the More they Stay the Same: Mexican Naturalization Before and After Welfare Reform, Bowling Green University, Working Paper Series 02-14, August 23, 2002.

[15] CIS Report at page 3.

[16] Karen Cunnyngham, Trends in Food Stamp Program Participation: 1994 to 2000, Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, June 2002.

[17]

See, e.g.,

[18] Leighton Ku and Sheetal Matani, “Left Out: Immigrants’ Access to Health Care and Insurance,” Health Affairs, (Jan./Feb. 2001) 20(1):247-56.

[19]

Congressional Budget Office, Cost Estimate of H.R. 4737, Work,

[20] Sean Higgins, “

[21] CIS report at page 17.

[22]

See John Holahan,