A D.C. Earned Income Tax Credit Could

Provide

Tax Relief and Reduce Child Poverty

by Robert Zahradnik and

Iris J. Lav

Summary

Earned Income Tax Credits provide tax refunds to working poor and near-poor families with children and boost the incomes of families seeking to work their way out of poverty. The federal government and 11 states, including the District of Columbia's neighbor Maryland, already offer EITCs. In addition, Montgomery County just enacted its own EITC to augment Maryland's state EITC.

State EITC's typically are based on the federal EITC. The federal EITC is the nation's most effective program for lifting working families with children out of poverty. Moreover, research shows the EITC provides a positive incentive for welfare recipients to enter the workforce. State EITCs add to these effects. As in other states, a District EITC could be structured as a percentage of the federal credit.

A District EITC would benefit approximately 54,000 D.C. households. It would provide low-income District residents with relief from the high tax burdens they face, help reduce poverty rates, and support efforts to move families from welfare to work.

Provide Low Income Tax Relief

- A District EITC would reduce District taxes paid by low- and moderate- income families. The $288 million tax cut in the District's Tax Parity Act of 1999 provided little benefit to families with income slightly above the poverty line. Such poor D.C. families pay among the highest income taxes in the country.

- If the lower tax rates in the Tax Parity Act were fully in effect today, a two-parent family of four with income at 125 percent of the federal poverty line would pay D.C. income tax of approximately $600. Even with the rate reduction, the District remains among the four states with the highest income tax burden on near-poor families.(1)

- The District's low-income tax credit does offset 100 percent of the taxes owed by families with incomes at or below a level that is roughly equal to the poverty line. Families just above the ceiling, however, are not eligible for any portion of the low-income credit and thus are liable for the full amount of the D.C. income tax. The structure of the low-income credit results in an income tax "cliff" where a single additional dollar of income triggers a large amount of tax. A D.C. EITC would lessen the tax burden on families with income modestly above the poverty line and would result in a much more gradual increase in the tax liability for such families.

- While the recently enacted Tax Parity Act made reductions in the income tax, it did not reduce the D.C. sales taxes that are the largest component of the tax burden of the lowest-income D.C. residents. A refundable EITC would help offset a portion of the sales tax burden poor residents face.

Reduce Poverty

- A District EITC would be refundable. This means a family would receive a refund check if the size of its EITC exceeds its tax bill. The District's current low-income credit is not refundable and does not provide additional income support to help lift families out of poverty.

- A refundable District EITC would reduce poverty among working families with children. Despite the robust economy, the District poverty rate remains high, about 23 percent. Over one-third of D.C. children are poor.

- Many of these poor families have at least one worker. In fact, more than 60 percent of the District's poor families with children include at least one working adult. On average those adults work 35 weeks out of the year. Yet for many families even the combination of the federal EITC and a full-time, year-round job are insufficient to support a family at the poverty line. Because it is targeted to low-income working parents, a District EITC would reduce the gap between working families' incomes and the poverty line and could lift some families out of poverty.

Support Welfare Reform

- A District EITC would support welfare reform by further boosting the incomes of families that move from welfare to work. Recent academic research shows that the federal EITC has positive effects in encouraging parents to enter the labor force.

- Many welfare recipients enter the workforce at relatively low wage levels. An EITC would help meet the ongoing expenses associated with working, such as transportation and child care, and could help families cope with unforeseen costs that otherwise might drive them back onto public assistance.

A D.C. EITC

The benefits to working poor families in the District from a refundable EITC set at 25 percent of the federal credit for families with children would be significant. If an EITC had been in effect in 1999:

- A family of four with two children and one parent working full-time, year-round, at $7.00 per hour would have earnings of $14,560 per year. After subtracting federal payroll taxes, adding the federal EITC of $3,374 and accounting for the District income taxes and low-income credit, the family's cash income would be $16,820, about $200 below the poverty line for a family of four. The proposed D.C. EITC set at 25 percent of the federal credit would give that family an additional $420, enough to bring the family just above the estimated poverty line of $17,027 for a family of four.

- A family of four with income of $19,000, slightly above the poverty line, would receive a D.C. EITC of $610, eliminating the majority of their District tax liability of $722. Under current law, this family would owe the full $722 in District income taxes.

There also is a federal EITC for workers between the ages of 25 and 64 who do not have children living with them, although it is much smaller and has much lower income limits than the EITC for families with children. Providing a D.C. EITC set at 100 percent of the federal credit for individuals and families without children could help the large number of poor and near-poor District families who do not have children.

- The maximum federal EITC for workers without qualifying children is $347 in 1999. Only workers with income below $10,200 can receive this type of EITC. If a District EITC were set at 25 percent of the federal EITC for workers without children, the maximum would be only $87.

- Census data indicates that the District has a large number of poor families with no children. In fact, the Census estimates that among families in the District that meet the income and family structure requirements of the federal EITC, some 35 percent have no children. (Nationwide, 27 percent of such families have no children.)(2) The high proportion of very low income individuals and families without children in the District suggests that specific measures, such as a D.C. EITC set at 100 percent of the federal credit, could be particularly appropriate for this population.

The estimated FY 2001 cost of a refundable EITC set at 25 percent of the federal credit for families with children and 100 percent of the federal credit for families without children is $20.1 million.

The Federal Earned Income Tax Credit as Context

To understand why a District EITC could serve important policy goals, it is useful first to look at the role played by the federal EITC. The federal EITC is a tax credit for low- and moderate-income workers, primarily those with children, designed to offset the burden of Social Security payroll taxes, supplement earnings, and complement efforts to help families make the transition from welfare to work. The EITC was enacted in 1975 primarily as a means of tax relief. It has been expanded three times, in 1986, 1990, and 1993. (The 1993 expansion was phased in through tax year 1996; President Clinton has proposed an additional expansion which is discussed below.) Through these expansions, the EITC became a central element of federal efforts to boost income from work and lessen poverty among families with children, often called the "make work pay" strategy.

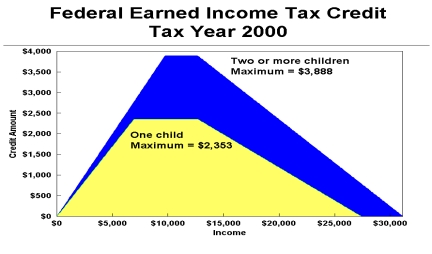

The maximum EITC benefit for tax year 2000 is $3,888 for families with two or more children and $2,353 for families with one child. The greater EITC benefit for larger families reflects a recognition that larger families face higher living expenses than smaller families. Workers without a qualifying child also may receive an EITC, but the maximum credit for individuals or couples without children is $353 in 2000, much lower than the credit for families with children.

The actual EITC benefit that an eligible family receives depends on the family's income. For families with very low earnings, the value of the EITC increases as earnings rise. Families with two or more children receive an EITC equal to 40 cents for each dollar up to $9,720 earned in 2000, for a maximum benefit of $3,888. Families with one child receive an EITC equal to 34 cents for each dollar earned up to $6,920 of earnings, for a maximum benefit of $2,353. Both types of families continue to be eligible for the maximum credit until income reaches $12,690. For families with incomes above $12,690, the EITC phases out as earnings rise. Families with two or more children are eligible for some EITC benefit until income exceeds $31,152, while families with one child remain eligible for some EITC benefit until income exceeds $27,413.

President Clinton recently proposed adding a "third tier" to the federal EITC that could provide higher amounts to families with three or more children. These larger families would receive a maximum credit of $4,491 - about a $500 increase over the current maximum credit for families with two or more children in 2001. The proposal would also increase the phase-in rate for families with three or more children from 40 cents to 45 cents for every additional dollar earned. The new proposed "tier" is designed to address the fact that 60 percent of poor children are in families with three or more children. This proposal will be considered as part of the President's FY 2001 Budget.

The federal EITC is a refundable credit, which means that if the credit amount is larger than a family's income tax bill, the family receives a refund check. This refundability allows families to take full advantage of the credit even if they owe little or nothing in federal income taxes.

The structure of the federal EITC thus boosts the incomes of working poor families, including those making the transition from welfare to work, and provides continuing assistance to working families with incomes modestly above the poverty line. Since many of these families still struggle to make ends meet and may be one or two paychecks away from needing to rely on assistance, the EITC helps people support their families through work and remain off welfare. (Research demonstrating that the EITC encourages welfare recipients to enter the workforce is discussed below.)

|

State Earned Income Tax Credits Based on the Federal Credit Refundable credits Non-refundable credits |

Eleven states currently offer an EITC. In the last two years, six states have enacted new EITCs or substantially expanded existing EITCs. Colorado, Kansas, Massachusetts and Oregon enacted new EITCs. Minnesota expanded its average EITC for families with children by about two-thirds, and Maryland augmented its existing EITC to provide a refundable credit.

In addition, one of the District's bordering jurisdictions, Montgomery County, recently approved a bill to enact a county-level EITC. Montgomery County will match Maryland's state EITC for each recipient who lives in Montgomery County. This county payment will provide assistance to some 12,000 of the county's poorest families with children.

Such credits have support across the political spectrum. EITCs have been enacted in states led by Republicans, in states led by Democrats, and in states with bipartisan leadership. The credits are supported by businesses as well as by social service advocates.

A District EITC Would Accomplish Three Key Policy Goals

A District EITC could reduce the high burden of District taxes currently faced by low- and moderate-income families. It also would help reduce the District's high rate of poverty among working families with children. In addition, a District EITC would support welfare reform by further boosting the incomes of families that move from welfare to work.

District EITC Would Reduce Taxes for Low and Moderate Income Families

The District recently enacted a large tax cut, the Tax Parity Act of 1999, that is projected to cost $59 million in FY 2000 with the cost growing to $288 million in FY 2004. The fully implemented tax cut has several provisions affecting the District's income tax, including a reduction in tax rates and an increase in the income level at which the highest tax bracket begins.(3)

The lowest-income D.C. residents will receive the least benefit from the income tax cut. See above figure. For these taxpayers, the income tax cut when fully phased in will equal only 0.6 percent of income. By contrast, upper-middle-income D.C. taxpayers will receive income tax cuts that average 1.8 percent of income, or three times greater then the income tax relief for the poorest District residents.

In addition, the Tax Parity Act failed to address the problem that near-poor families with income slightly above the poverty line pay income taxes that are among the highest in the country. For example,

- For a two-parent family of four with income at 125 percent of the federal poverty line in 1998, about $20,820, the D.C. income tax was $866. This was a higher income tax burden levied on such a family than in any other state in the country. Even if the lower rates of the Tax Parity Act were fully phased in, this family would still pay D.C. income tax of $600. Even with the rate reduction, the District remains among the four states with the highest income tax burden on near-poor families.(4)

- Among the 41 states that levy income taxes, the median income tax on a two-parent family of four with income at 125 percent of the federal poverty line in 1998 was $192, about one-third the level that the tax burden would be on such a family in D.C. if the Tax Parity Act were fully in effect.

- For a family of three headed by a single parent with income at 125 percent of the federal poverty line, about $16,250 in 1998, the D.C. income tax was $527, the third-highest in the country behind only Hawaii and Kentucky. The fully phased in Tax Parity Act would reduce the tax to $351 — again remaining among the highest in the country.

- Among the 41 states that levy income taxes, the median income tax on a single-parent family of three with income at 125 percent of the federal poverty line in 1998 was $94, about one-fourth the $351 in D.C. income tax the family would pay under the lower rates of the Tax Parity Act.

The high tax rate on near-poor families is exacerbated by the structure of the District's low-income tax credit. The credit offsets 100 percent of District income taxes for individuals and families up to a certain income. This level may be described as a "no-tax floor." In tax year 1999, the no-tax floor was set at $18,204 for a family of four.(5) Thus a family with poverty-level income — estimated at $17,027 in 1999 for a family of four — owed no income tax because its income was below the "no-tax floor." Once family income rises above the "no-tax floor" however, the family is not eligible for any portion of the low-income credit, and thus must pay the full amount of the D.C. income tax.

|

1999 D.C. Tax Liability |

|

|

Income |

Tax Liability |

|

$18,204 |

$0 |

|

$18,205 |

$658 |

The D.C. low-income credit is quite effective in targeting virtually all of its benefits to poor families. On the other hand, as a family works its way out of poverty, it can find itself faced with an income tax "cliff" where a single additional dollar of income triggers a large amount of tax. In 1999, for example, a two-parent family of four with income of $18,204 received a low-income credit of $658 which fully offset the usual tax liability at that income level. If such a family earned $18,205, however, it was no longer eligible for the tax credit and faced tax liability of $658. One additional dollar of income increases income tax liability by $658.

The current structure of the low-income credit creates a work disincentive for families just emerging from poverty. It is also incompatible with the goal of welfare reform, which is to help families earn sufficient amounts to support their families and escape from poverty.

An EITC could be an improvement over the low-income credit for three reasons.

- Unlike the low-income credit, the EITC would be refundable. It thus provides a resource for families to meet work-related costs such as child care and transportation.

- The EITC reduces the income tax "cliff" by allowing a much more gradual increase in the tax liability for families with income modestly above the poverty line.

- A District EITC would reduce taxes on working families with incomes of up to $30,000, a group that arguably received short shrift in the Tax Parity Act of 1999.

Finally, while the tax cut made significant reductions in the income tax that D.C. residents will pay, it did not reduce the D.C. sales taxes that are the largest component of the tax burden of the lowest income D.C. residents. In fact, the lowest 20 percent of taxpayers in the District pay 6.5 percent of family income in District sales taxes. By contrast, the top 1 percent of taxpayers pay only 1 percent of family income in District sales taxes. A D.C. EITC would address this problem by providing poor District families with an income supplement to offset the high level of District sales tax that they owe.(6)

A Refundable EITC Would Boost Incomes for Working Poor Families in the District

Despite the robust economy, the District poverty rate remains high, about 23 percent. Among children, the poverty rate is even higher, an estimated 38 percent.(7) What makes the EITC particularly useful as an anti-poverty tool is the fact that many poor families are already working.

- 61 percent of all poor families with children in the District had a worker. All of these families with earnings would qualify for the EITC.

- The average working-poor family in the District includes one or more adults who work 35 weeks per year — about 9 out of 12 months.

- Among all poor families in the District, 35 percent rely on earnings from a job for over half of their income.

- Even among families receiving public assistance, 45 percent included a parent who worked at least part of the year.

As stated above, 61 percent of poor families with children, along with a large number of families with incomes somewhat above the poverty line, would be eligible for a District EITC. A refundable District EITC would lift the incomes of many poor families above the poverty line; for others, the poverty gap — the amount by which their incomes fall short of the poverty line — would be reduced.

Recent research on the effect of poverty on children has shown that when all other factors are controlled for, poverty can have a substantial effect on child and adolescent well-being. Children who grow up in families with incomes below the poverty line have poorer health, higher rates of learning disabilities and developmental delays, and poorer school achievement. They are far more likely to be unemployed as adults than children who were not poor. Lifting children out of poverty can have long-term positive effects on the District's economy and future budgetary expenditures.

A District EITC Would Complement Welfare Reform

A District EITC would build on the success of the federal EITC in combating poverty among working families with children. Closing or at least substantially reducing the poverty gap for many working families is well within the reach of the District.

The use of a District EITC to enable low-wage workers to escape poverty is of particular relevance to the District's welfare reform efforts. Many welfare recipients that take jobs continue to have very low incomes, often below poverty. Recent evidence from several states shows that although most welfare recipients who find jobs are employed close to full-time, many of them earn wages at or only modestly above the minimum wage. Moreover, many do not qualify for paid vacation or sick leave, forcing them to take unpaid leave for reasons such as a child's illness. A number of studies show that welfare recipients who find jobs have average earnings of $2,000 to $2,700 per quarter, or $8,000 to $10,800 per year; many earn less.(8) Earnings in that income range are insufficient to lift a single-parent family of three above the poverty line, even with the federal EITC. A combination of the federal EITC and a D.C. EITC, however, can close the poverty gap for many welfare recipients as they move into the workforce.

The District has enacted several policies recently to subsidize the efforts of welfare recipients to enter and remain in the workforce. First, the District has expanded access to child care and to health insurance to children and working parents with income up to 200 percent of the poverty threshold. In addition, the District allows an "earned income disregard" in their welfare program, under which welfare benefits phase out gradually as family earnings increase, thereby helping ease the transition from welfare to work. The District's "earned income disregard" allows recipients to earn $100 without any loss of benefits and then reduces benefits at a rate of 50 cents for every dollar of income above this level. The District has also increased the "asset limit" for welfare eligibility to move it in line with the test used in determining food stamp benefits.

The missing piece in the District's package of policies to assist the working poor in moving from welfare to work is a state-type EITC. Welfare benefits tend to phase out fairly quickly as income rises even with the District's fairly generous earned income disregard. The loss of welfare benefits for families at relatively low earnings levels can be offset in part by the EITC benefits such families receive. As noted earlier, EITC benefits increase as earnings increase for workers with very low wages. In this way, the EITC complements the earned income disregard, as well as the other policies, by targeting assistance to families that are making or have completed the transition from welfare to work.

Jurisdictions also have an interest in supporting the work efforts of low- and moderate-income families who have long since left the welfare rolls or who have never received welfare benefits. EITCs help meet the ongoing expenses associated with working, such as transportation and child care, and may allow families to cope with unforeseen costs that otherwise might drive them onto public assistance.

Recent evidence confirms that the federal EITC has been effective at meeting the goals of making work pay better and reducing poverty among working families.

- The wage supplement offered by the federal EITC has encouraged hundreds of thousands of welfare recipients to enter the workforce. Several academic studies, using a variety of sources of data, show that the federal EITC, more than any other factor, accounts for the increase in workforce participation among single mothers over the last 15 years. (See box.)

- The additional income provided by the federal EITC lifts more than four million people out of poverty, including more than two million children, who would have been poor without it, according to an analysis of Census Bureau data by the President's Council of Economic Advisers. The EITC lifts more working families out of poverty than any other government program.(9)

- Families can use their EITCs to make investments that may over the long term reduce their dependence on government benefits. In 1996, a team of researchers from Syracuse University and the Center for Law and Human services surveyed close to 1,000 EITC recipients. Over half of those surveyed spent their EITC refunds on the kinds of financial investments or human capital investments that are likely to increase earnings or to protect against future economic shocks such as loss of a job. Those investments included paying for tuition or other education expenses, increasing access to jobs through car repairs and other transportation improvements, moving to a new neighborhood, or putting money in a savings account.(10)

|

Research Findings on the Effectiveness of the EITC Several recent academic studies indicate that the EITC has positive effects in inducing more single parents to go to work, reducing welfare receipt, and moderating the growing income gaps between rich and poor Americans.Harvard economist Jeffrey Liebman, who has conducted a series of studies on the EITC, has noted that workforce participation among single women with children has risen dramatically since the mid-1980s.a In 1984, some 72.7 percent of single women with children worked during the year. In 1996, some 82.1 percent did. The increase has been most pronounced among women with less than high school education. During this same period there was no increase in work effort among single women without children. A number of researchers have found that the large expansions of the EITC since the mid-1980s have been a major factor behind the trend toward greater workforce participation. Studies by Liebman and University of California economist Nada Eissa find a sizable EITC effect in inducing more single women with children to work.b In addition, a recent study by Northwestern University economists Bruce Meyer and Dan Rosenbaum finds that a large share of the increase in employment of single mothers in recent years can be attributed to expansions of the EITC. They find that the EITC expansions explain more than half of the increase in employment among single mothers over the 1984-1996 period.c These findings are consistent with an earlier study by Stacy Dickert, Scott Hauser, and John Karl Scholz of the University of Wisconsin, which projected that the EITC expansions in the 1993 budget law would generate a reduction in welfare receipt. Dickert, Hauser, and Scholz estimated that the 1993 EITC expansions would induce approximately 500,000 families to move from welfare to the workforce.d Finally, Liebman also has found that the EITC moderates the gap between rich and poor. During the past 20 years, the share of national income received by the poorest fifth of households with children has declined, while the share of income received by the top fifth has risen sharply. Liebman found that the EITC offsets between one-fourth and one-third of the decline that occurred during this period in the share of income the poorest fifth of households with children receive. A discussion of these and other studies on the EITC’s effectiveness may be found in the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities publication New Research Findings on the Effects of the Earned Income Tax Credit, March 16, 1998. _______________________ a Jeffrey B. Liebman, "The Impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit on Incentives and Income Distribution," in James M. Poterba, ed., Tax Policy and the Economy, Vol. 12, MIT Press, 1998.b Nada Eissa and Jeffrey B. Liebman, "Labor Supply Response to the Earned Income Tax Credit," Quarterly Journal of Economics, May 1996, 112(2), pp. 605-637 c Bruce D. Meyer and Dan T. Rosenbaum, "Welfare, The Earned Income Tax Credit, and the Labor Supply of Single Mothers," March 7, 1998. d Stacy Dickert, Scott Hauser, and John Karl Scholz, "The Earned Income Tax Credit and Transfer Programs: A Study of Labor Market and Program Participation," in James M. Poterba, ed., Tax Policy and the Economy, Vol. 9, MIT Press, 1995. |

Ten of the eleven state EITCs piggy-back on the federal EITC; these 10 states use federal eligibility rules and express the state credit as a specified percentage of the federal credit. An EITC that piggybacks on the federal credit is relatively easy for a state to administer and also is easy for families claiming the EITC. To determine its state EITC benefit, a family need only write its federal benefit on its state return and then multiply the federal amount by the state EITC percentage.

Assuming a District's EITC would piggy-back on the federal credit, there are four additional issues to consider in designing the EITC: whether the EITC will be refundable or non-refundable, the percentage of the federal credit at which to set the District credit, whether to provide a greater percentage of the federal EITC to poor District residents without children, and the interaction with the District's low-income credit.

There is another option the District could consider. This option is to adjust a D.C. EITC to give larger benefits to larger families. President Clinton recently proposed adding another "tier" to the federal EITC for families with 3 or more children (see description above.) If the federal proposal is enacted, it would be incorporated automatically in a D.C. EITC. Adjusting a D.C. EITC to give larger benefits to larger families is discussed in the appendix.

Refundable Versus Non-Refundable EITCs

Under a refundable EITC, a family receives a refund check if the size of its EITC exceeds its tax bill. For example, if a taxpayer owes $330 in District income taxes and qualifies for a $900 District EITC, the first $330 of the EITC offsets the income tax and the remaining $570 is received as a refund check. (If the $330 of income tax were withheld during the year, the taxpayer would receive the entire $900 as a check. Nevertheless, the EITC would offset $330 in tax liability and provide a $570 income supplement.) If an EITC is non-refundable, the family's income tax liability would be eliminated. The remaining $570 of the credit, however, would be forfeited.

The distinction between refundable and non-refundable credits is important. A non-refundable EITC does not supplement a family's income above its earnings and thus does not lift any families with poverty-level wages out of poverty. A refundable EITC, by contrast, can be used to boost the incomes of low-income working families, including those making the transition from welfare to work, as the federal EITC does. Making a District EITC refundable also allows it to be used to offset the high level of sales and excise taxes paid by low-income families.

The importance of refundability is reflected in the decision of most states to make their EITCs refundable. Eight of the 11 states with a state EITC — Colorado, Kansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York, Vermont, and Wisconsin — offer refundable credits. The number and value of refundable EITCs have increased in the last two years.

- The new credits enacted in Colorado, Massachusetts and Kansas are refundable.

- Minnesota substantially expanded its refundable credit for families with children. The credit, which had been set at 15 percent of the federal credit, now equals 20 to 42 percent of the federal credit depending on family size and income. The amount of the credit remains 15 percent for workers that do not have children. The change increased the average EITC recipient's state credit by about two-thirds.

- Maryland, which previously offered a non-refundable credit that benefitted only those families with incomes above the poverty line, enacted a refundable credit as well. The new, refundable credit is set at 10 percent of the federal EITC, increasing to 15 percent over the next three years.(11)

- One of the District's bordering jurisdictions, Montgomery County, recently approved a bill to enact a county-level refundable EITC. Montgomery County will match Maryland's state EITC for each recipient who lives in Montgomery County. This county payment will provide assistance to some 12,000 of the county's poorest families with children. The effective EITC in Montgomery County will be 30 percent of the federal EITC once both the Maryland and Montgomery County EITC's are fully implemented in 2001.

Among states with new EITCs, only Oregon enacted a non-refundable credit. A refundable version of Oregon's EITC received bipartisan support but was not enacted due to last-minute budget constraints.

Setting the Size of a District EITC

The EITCs in the states with refundable credits generally range from 10 percent to 25 percent of the federal credit. Choosing the percentage of the federal EITC at which the District credit is set should be based on several considerations. One consideration is the cost that can be afforded. Affordability depends on the amount of resources available to finance an EITC. Options for financing a D.C. EITC will be discussed in more detail below.

A second factor that affects the desirable size of the credit is the structure of the District's low-income credit. As discussed earlier, a family working its way out of poverty can find itself faced with an income tax "cliff" where a single additional dollar of income triggers a large amount of tax. In 1999, for example, a two-parent family of four with income of $18,204 received a low-income credit of $658 which fully offset the usual tax liability at that income level. If such a family earned $18,205, however, it was no longer eligible for the tax credit and faced tax liability of $658. One additional dollar of income increases income tax liability by $658. A D.C. EITC would result in a much more gradual increase in the tax liability for families with income modestly above the poverty line.

It is important, however, that the process of assisting near-poor families does not result in higher taxes on poor families. Attention must therefore be paid to the interaction between a new District EITC and the existing low-income credit. To avoid unnecessary complexity, it would be desirable to set a District EITC at a large enough percentage of the federal credit so that the vast majority of poor families would receive an equal or greater benefit from the EITC than from the current low-income credit. (The interaction of the EITC and low-income credit is discussed in more detail below.)

A D.C. EITC set at 25 percent of the federal EITC would provide greater tax relief than the low-income credit for most of the working poor families with children in the District. For example, the figure below compares the taxes owed by a family of four in the District under a 25 percent EITC and under the low-income credit. The graphic shows that at virtually every income level up to approximately $30,000, the family is better off under the EITC compared to the low-income credit. Families for whom the low-income credit now eliminates D.C. income taxes would receive a refund while families with incomes above the low-income credit ceiling and below approximately $30,000 would receive a tax cut.

A District EITC set at 25 percent of the federal credit would substantially reduce the problem of the high tax burden faced by near poor families in the District. A 25 percent EITC would reduce taxes for a family of four with two children with income at 125 percent of the federal poverty line in 1998 from $866 to $353. Assuming the rates from the fully phased-in tax cut, the EITC reduces taxes on this family from $600 to $86. Thus, the EITC would reduce taxes on near-poor families to below the median tax burden of the 41 states that impose an income tax of $192.

Adjusting the EITC for Poor Families without Children

Another decision that must be made in designing an EITC for the District is whether or not to enhance the credit for low-income workers who do not have a qualifying child living with them. Such workers between the ages of 25 and 64 were made eligible for a modest federal EITC for the first time as part of the 1993 expansion.

The maximum federal EITC for workers without qualifying children is $353 in 2000. Only workers with income below $10,380 can receive this type of EITC. If a District EITC were set at 25 percent of the federal EITC for workers without children, the maximum would be only $88.

Census data indicates that the District has a large number of poor families with no children. In fact, the Census estimates that among families in the District that meet the income and family structure requirements of the federal EITC, 35 percent have no children — compared to the national figure of 27 percent.(12) To ensure that these families receive a credit that assists them in moving out of poverty, the District should consider increasing the percentage of the federal credit to 100 percent of the federal credit for poor families without children.

Interaction with the Low-income Credit

The District has two options for developing an EITC in the context of its income tax, which currently includes a low-income credit:

- implement the EITC as a replacement for the low-income credit, or

- retain the low-income credit for eligible taxpayers for whom the EITC does not eliminate tax liability.

As discussed above, D.C.'s current low-income credit offsets fully the income taxes that otherwise would be owed by families and individuals with incomes at or below a level that is roughly equal to the federal poverty line. This level may be described as a "no-tax floor." In tax year 1999, the no-tax floor was set at $18,204 for a family of four. Thus a family with poverty-level income — estimated at $17,027 in 1999 for a family of four — owed no income tax because its income was below the "no-tax floor." Once family income rises above the "no-tax floor" however, the family is not eligible for any portion of the low-income credit, and thus must pay the full amount of the D.C. income tax.

The EITC differs from the low-income credit in several significant ways. First, the benefits of the EITC are initially phased in, reach a maximum level and then are gradually phased out up to about $30,000 for a family of four. Thus, the EITC does not have an income "cliff" whereby one additional dollar of income results in a large increase in tax liability. Second, as discussed above, the EITC is typically refundable. This means that when the credit exceeds the amount of taxes owed, families receive the difference as an income supplement. On both of these dimensions, the EITC provides greater tax relief than the low-income credit.

On the other hand, the low income credit does a better job than the EITC of adjusting for family size. The federal EITC does not provide additional benefits for families with more than two children.(13) By contrast, the low-income credit adjusts its benefit level for families with up to nine children. This means that simply replacing the low-income credit with an EITC could result in tax increases for some larger low-income families. If a D.C. EITC were set at 25 percent of the federal credit for example, families of six with incomes between about $20,000 and $24,000 would have higher tax liability under the EITC than under current law using the low-income credit.

The low-income credit also provides tax relief to a larger range of families without children. If a D.C. EITC were set at 100 percent of the federal credit for families without children, a married couple without children with income between about $8,000 and $13,000 would have some D.C. tax liability remaining after the application of the EITC. The low-income credit fully offsets tax liability for these families.

To avoid tax increases on low-income families, the tax computation could be set up as follows. A family would first calculate its District tax liability with the EITC. Families with income below the low-income credit ceilings that have remaining tax liability after application of the EITC would be eligible to use the low-income credit instead of the EITC. For example, if a family of six had income between $20,000 and $24,000, it likely would use the low-income credit.

Allowing taxpayers to "choose" the low-income credit if the EITC does not fully eliminate tax liability is consistent with the practices in other states. Other states have used the EITC to complement and not replace existing low-income tax relief provisions. In fact, seven of the eleven states that offer an EITC eliminate taxes for families below the poverty line even when the EITC is excluded from the calculation.

The projected cost of a 25 percent refundable D.C. EITC in fiscal year 2001 is $18.5 million.(14) This estimate is based on two sets of data. The first set is Internal Revenue Service data on the amount of federal EITC claims filed by residents of each state. The second data source is the U.S. Department of Treasury's projections of the cost of the federal EITC in future years. Based on this data, the estimated cost of the federal EITC going to District residents in FY 2001 is $87 million.

The cost estimate of the D.C. EITC reflects the 25 percent rate for the D.C. credit, and an assumption that approximately 85 percent of D.C. residents who claim the federal credit would also claim the D.C. credit ($87 million X 25% X 85% = $18.5 million). Other states that have enacted EITCs, including New York, Wisconsin, and Vermont, have found that the participation rate for a state EITC in the first year after enactment was 80 to 85 percent of participation in the federal credit by state residents.(15)

The same procedure may be used to calculate the cost of the D.C. EITC set at other percentages. For example, the cost of a 30 percent EITC would be just over $22 million: $87 million times 30% times 85% = $22.2 million.

A D.C. EITC set at 25 percent of the federal credit for families with children and 100 percent for families without children would cost $20.1 million in FY 2001. The additional cost estimate of $1.6 million was developed using Census data to estimate the number of families without children that would receive the credit.

There are two primary options for financing a D.C. EITC:

- Using available local-source funds based on estimates of revenues and expenditures prepared during the formulation of the budget, and

- Using federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Block Grant funds for a portion of the credit as allowed by recently issued federal regulations.

Using local funds is the most common way that the District finances newly proposed tax or expenditure initiatives. For example, if the preliminary revenue and expenditure projections for the District's FY 2001 budget indicate a surplus, then the funds will be allocated to various policy options, such as an EITC. If no surplus is projected, then expenditure reductions or tax increases would be required to finance new initiatives.

The second option of using federal TANF funds is based on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recognition of the importance of state EITCs to welfare reform by declaring that state EITCs meet the purposes of the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families block grant program, which was created as part of the 1996 welfare law. In regulations issued in April, 1999, the department ruled that states may use the federal block grant to pay for the refundable portion of the EITC for TANF-eligible families.(16) The department also said that a state may finance an EITC with state dollars and count a portion of those dollars as part of the state's required expenditure of own-source funds — the so-called "maintenance-of-effort" or MOE requirement.

These federal regulations, combined with the availability of unspent welfare funds in the District, provide an opportunity to finance a portion of a D.C. EITC through this mechanism. Largely due to declines in welfare caseloads, the District has unspent federal block grant funds. A further reason the District might choose to spend TANF funds on an EITC is that many of the federal restrictions that apply to more traditional welfare expenditures would not apply to EITC expenditures. For example, the federal "time limit" — the requirement that most adult welfare recipients may not receive federally funded welfare payments for more than 60 months in their lifetimes — does not apply to state EITC payments from TANF funds.

States may use TANF or MOE funds only for refundable EITCs — that is, for credits that provide families a refund when the credit amount is greater than a family's tax bill. More specifically, states can count as TANF or MOE spending only the portion of an EITC that provides a refund in excess of tax liability. State EITCs that are non-refundable — those that only reduce or eliminate state income taxes that low-income families otherwise would owe but do not provide refunds — cannot be financed at all with federal funds and cannot count toward states' MOE requirements.(17)

Although many EITC recipients are not on welfare and have incomes above the District's welfare eligibility limits, the District can still finance the refundable portion of a state EITC with TANF or MOE funds. The welfare law requires that TANF and MOE funds be spent on needy families, but states are allowed to set the definition of "needy." Moreover, states are allowed to set differing financial eligibility rules for different TANF- or MOE-funded programs. It is not necessary that EITC recipients actually receive welfare benefits in order to be considered "TANF-eligible," nor is it necessary that their incomes fall below the poverty line or that their assets be limited to a certain amount. Rather, the District need only establish in its state plan an income eligibility limit that would include all recipients of EITC refunds.

Examples of How a D.C. EITC Would Affect Families

To understand the effect of a District EITC on individual families, it is useful to consider some examples based on tax year 1999 provisions.

- A family of four with two children and one parent working full-time, year-round, at $7.00 per hour — above the District minimum wage of $6.15 per hour — would have earnings of $14,560 per year. After subtracting federal payroll taxes, adding the federal EITC of $3,374 and accounting for the District income taxes and low-income credit, cash income would be $16,820, about $200 below the poverty line for a family of four. The proposed D.C. EITC set at 25 percent of the federal credit would give that family an additional $420, enough to bring the family just above the estimated poverty line of $17,027 for a family of four.

Additional examples comparing a D.C. EITC to current law are provided below.

|

Comparison of D.C. Tax Liability, 1999 |

|||||||

|

Gross Earnings |

D.C. Tax Liability Under Current Law |

D.C. Tax Liability Under D.C. EITC Set at 25% of Federal Credit |

|||||

|

Family of four with two children |

|||||||

|

No earnings |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

||||

|

Half-time minimum wage |

$6,396 |

$0 |

($640) |

||||

|

Full-time minimum wage |

$12,792 |

$0 |

($618) |

||||

|

Wages equal federal poverty line |

$17,027 |

$0 |

($141) |

||||

|

Wages equal 125% of poverty line |

$21,283 |

$904 |

$415 |

||||

|

Wages equal 200% of poverty line |

$34,053 |

$2,024 |

$2,024 |

||||

|

Family of three with two children |

|||||||

|

No earnings |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

||||

|

Half-time minimum wage |

$6,396 |

$0 |

($640) |

||||

|

Full-time minimum wage |

$12,792 |

$0 |

($618) |

||||

|

Wages equal federal poverty line |

$13,289 |

$0 |

($562) |

||||

|

Wages equal 125% of poverty line |

$16,611 |

$548 |

($188) |

||||

|

Wages equal 200% of poverty line |

$26,578 |

$1,328 |

$1,117 |

||||

APPENDIX: ADJUSTING THE FEDERAL CREDIT FOR LARGER FAMILIES

It would be possible for the District to choose to provide a larger EITC to larger-size families. The federal EITC, as discussed earlier, provides a small credit to families with no children, a larger credit to families with one child and the largest credit to families with two or more children. The federal EITC does not provide additional benefits for families with three children or more. As discussed earlier, President Clinton has proposed adding an additional tier with higher benefit levels to the federal EITC for families with three or more children. If this expansion is enacted, it would be incorporated automatically in a D.C. EITC. However, Congressional approval of the proposed federal EITC expansion, of course, is uncertain at this time.

The Census estimates that among families in the District that meet the income and family structure requirements of the federal EITC, 14 percent have three or more children.(18) Because wages do not adjust for family size, larger low- and moderate-income working families fall further and further behind an adequate standard of living than smaller families with the same number of workers. Also, the District's low-income credit currently provides additional benefits for two-parent families with up to eight children and one-parent families with up to nine children. To assist these families, the District could choose to use a larger percentage of the federal credit for families with three or more children.

End Notes:

1. This analysis compares the District tax liability with the tax rates for the fully implemented tax cut and the current low-income credit to the 1998 tax rates for other states.

2. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities' calculation based on data from the Current Population Survey, March 1996 - March 1999, Bureau of the Census. The March supplement of the Current Population Survey includes

data on a wide range of income and demographic variables. Based on this data and the relevant federal EITC parameters, Census estimates who would have received a federal EITC and the amount of the credit.

3. The tax changes include reducing the rate in the $0 to $10,000 bracket from 6.0 percent to 4.0 percent, reducing the rate in the $10,000 to $20,000 bracket from 8.0 percent to 6.0 percent, applying the 6.0 percent rate to taxable income up to $40,000, and reducing the top bracket rate for taxable income in excess of $40,000 from 9.5 percent to 8.5 percent. These changes are scheduled to be phased in over a number of years.

4. This analysis compares the District tax liability with the tax rates for the fully implemented tax cut and the current low-income credit to the 1998 tax rates for other states.

5. This income ceiling for D.C.'s no-tax floor is equivalent to the income level below which the family would owe no federal tax.

6. District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission. Taxing Simply, Taxing Fairly. (Washington, D.C.: 1998), 29.

7. The data in this section were calculated by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities from the U.S. Census Bureau's Current Population Survey, 1996 through 1998.

8. These studies are summarized in Welfare Recipients Who Find Jobs: What Do We Know About Their Employment and Earnings?, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November, 1998.

9. Good News for Low Income Families: Expansions in the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Minimum Wage, Council of Economic Advisers, December 1998. Also see the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities publication Strengths of the Safety Net: How the EITC, Social Security, and Other Government programs Affect Poverty, March 1998.

10. Timothy M. Smeeding, Katherin E. Ross, Michael O'Connor and Michael Simon, "The Economic Impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit," 1999.

11. Maryland taxpayers now have the option of choosing either the new, refundable credit or the previously existing non-refundable credit. The non-refundable credit is set at 50 percent; the refundable credit is set at 10 percent of the federal credit, rising to 15 percent over the next three years. Most families with incomes below the poverty line are likely to receive greater benefit from the smaller, refundable credit; most families with incomes above the poverty line are likely to receive greater benefit from the larger, non-refundable credit.

12. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities' calculation based on data from the Current Population Survey, March 1996 - March 1999, Bureau of the Census. The March supplement of the Current Population Survey includes data on a wide range of income and demographic variables. Based on this data and the relevant federal EITC parameters, Census estimates who would have received a federal EITC and the amount of the credit.

13. As discussed previously, President Clinton has proposed providing a larger benefit for families with three or more children. In addition, some states have adjusted their credit to provide greater benefits to larger families. This option is discussed in the appendix.

14. This is a gross estimate that does not take into account the anticipated savings from significantly fewer families using the current low-income credit. As a result, the net cost will be less than $18.5 million.

15. For more information on state EITC cost estimates, see Nicholas Johnson, Estimating the Cost of a State Earned Income Tax Credit, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November, 1999.

16. There is one exception: a state cannot pay for any portion of an EITC in a given year with unspent federal

funds carried over from a previous year.

17. The regulations also bar states from spending federal funds or state MOE funds on property tax credits,

sales tax credits, or other tax credits that expressly offset tax liability. However, they permit states to spend those

funds on the refundable portion of other work-related tax credits such as child care credits.

18. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities' calculation based on data from the Current Population Survey,

March 1996 - March 1999, Bureau of the Census. The March supplement of the Current Population Survey

includes data on a wide range of income and demographic variables. Based on this data and the relevant federal

EITC parameters, Census estimates who would have received a federal EITC and the amount of the credit.