Revised June 5, 2003

FEDERAL TAX CHANGES LIKELY TO COST STATES

BILLIONS OF DOLLARS IN COMING YEARS

“Decoupling” May Protect Some Revenue

by

Nicholas Johnson

| PDF of this report |

| If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

State governments stand to lose several billion dollars in tax revenue as a result of the federal tax law enacted May 28. This loss of tax revenue, if states do not act to reverse it, would undermine the stimulative impact of the federal tax package and partially offset the direct aid to states contained in the tax bill.

Over the next two state fiscal years, state tax revenue is likely to be reduced by some $3 billion due to provisions in the federal tax bill that are likely to carry over into state tax calculations. The ten-year cost to states could be $16 billion or more, if the new provisions do not “sunset” but rather are extended or made permanent, and if states do not act to “decouple” their tax codes from the new federal laws. Nearly every state with a personal or corporate income tax — some 44 states — could be affected.

Three provisions of the tax plan would reduce state revenue.

Note that reductions in federal tax rates do not reduce state tax revenue, because no state piggybacks on federal tax rates. Therefore, none of the changes in tax rates or tax brackets — including the reductions in the tax rates for dividends and capital gains received — would reduce state revenues. [1]

|

By SFY |

2004 |

2005 |

2003-2012 (only if provisions are made permanent) |

|

Expansion of bonus depreciation |

1.1 |

0.6 |

12.5 |

|

Section 179 expensing |

0.6 |

0.5 |

5.2 |

|

Standard deduction increase |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.7 |

|

Total |

1.8 |

1.2 |

18.4 |

Notes: Figures for 2004 and 2004 assume

provisions expire as scheduled in the bill. Some totals do not add due to

rounding. Estimates for bonus depreciation and Section 179 expensing are

based on Joint Committee on Taxation estimates of federal impact and on each

state’s relative personal and corporate income tax collections. Estimates

for standard deduction are based on

The revenue loss would occur at a particularly difficult time for states. States have closed or are in the process of closing deficits for state fiscal year 2003 that totaled nearly $80 billion, along with deficits for fiscal year 2004 that exceed $70 billion. These deficits have been closed by a combination of depleting reserves, raising taxes, and cutting needed programs such as education and health insurance for low-income families. Most observers expect state fiscal problems to continue in fiscal year 2005, and further rounds of tax increases and program cuts will be made as states struggle to meet their balanced budget requirements. Although the tax bill does contain $20 billion in new federal aid to states, most states will still face budget difficulties even after this aid is distributed.

“Bonus Depreciation” Expansion Likely to Cost States $1.7 Billion Through 2005

Under normal tax law, the cost of purchases of machinery or equipment cannot be claimed fully as a business expense in the year of purchase but rather must be spread over the useful lifetime of the equipment. The 2002 federal tax law allowed firms to deduct up to 30 percent of the cost of purchasing machinery or equipment in the first year, as long as the item was purchased between September 2001 and September 2004. The new tax law expands the percentage to 50 percent and extends it to December 2004.

As noted above, a majority of states

have decoupled from bonus depreciation. But some 13 states —

Senate and House “Section 179 Expensing” Provision Would Cost States About $1.1 Billion Through 2005

Every one of the 45 states with a

personal or corporate income tax, except

Standard Deduction Increase Costs States about $240 Million Through 2005

Ten states presently conform to the

federal standard deduction, which is increasing for married couples in tax

years 2003 and 2004 under the new tax law. The states are

What about the Out-years?

The bonus depreciation extension and the standard deduction increase are scheduled to “sunset” at the end of the 2004 tax year; the Section 179 provision is scheduled to sunset at the end of 2005. If these provisions are allowed to expire, states would recoup some of the revenue loss from bonus depreciation and Section 179 expensing in later years, because the immediate deductions substitute for the deductions that otherwise would be taken in future years. If, on the other hand, the provisions are extended, states would lose additional revenue — as much as $18 billion or more over 10 years. It is not clear whether these provisions are among those that lawmakers have indicated will be targeted for extension in next year’s tax bill.

Can States Decouple?

The likely revenue losses described in this paper come at a terrible time for states. The fiscal crisis is forcing states to enact major spending cuts, as well as tax increases and increased borrowing.

In many states, revenue losses from the new federal law may be at least partially avoidable. States are not required to conform their corporate or personal income tax codes to federal law, although most do as a matter of administrative convenience. Ending the practice of conformity — that is, decoupling — can be a significant challenge. It can be politically difficult and sometimes may require legislative supermajorities or popular referenda. It can also pose administrative challenges. But decoupling also can be an attractive alternative to other forms of tax increases, spending cuts, or other measures that may be needed to balance state budgets.

Decoupling from bonus depreciation changes

The majority of states with personal and/or corporate income taxes decoupled from last spring’s bonus depreciation law. Most of those states will not lose revenue from the new expansion. A few states that are now decoupled — in particular states that did not decouple for the full three-year period in which the original bonus depreciation provision was in effect, including Missouri and North Carolina — will need to update their codes to specify that the new bonus depreciation rules do not apply. Some other decoupled states may also need to clarify that the new law does not apply.

A smaller number of states with income taxes, some 14 states, fully or partially conformed to the bonus depreciation rules enacted in 2002. Most of those 14 states automatically will conform to the new rules and therefore will lose revenue from the new law, unless they enact legislation specifically to decouple. But a few of those 14 conforming states, including Florida and West Virginia, likely will conform to the new rules only if they enact legislation specifically to conform.

Decoupling from Section 179 expensing changes

Some states will conform automatically to the new Section 179 expensing rules. In those states, legislative action would be required to avoid the revenue loss.

Other states, such as Virginia and a number of other states, would require legislative action to update their tax codes in order to conform with the changes. In those states, no legislative action is needed to decouple from the federal changes; instead policymakers need only avoid enacting a change in the Section 179 rules. In states that routinely adopt changes in the federal tax code each year, the Section 179 rules would have to be excluded specifically from the adoption.

Note that many of the businesses that utilize the Section 179 rules are relatively small. It may be administratively difficult for states to require a multitude of small businesses to follow different expensing rules for their state taxes than those used for federal tax calculations. Instead of simply disallowing the federal expensing changes, states might be advised to allow the Section 179 expensing but then require an “add-back” equivalent to some portion of the expensing. The add-back would then be subtracted from the business’s income in future years. This method is already used by several of the states as a method of decoupling from the bonus depreciation provision.

Decoupling from changes to the standard deduction for joint filers

Of the ten states with standard deductions that equal the federal standard deduction, some will conform automatically to the change. The others likely will face significant political pressure to conform. It is worth noting that the new federal tax law merely accelerates a change that was enacted in the 2001 tax law. States that have previously acted to conform to the 2001 law, as most of the ten states have done, would merely be delaying the increase in the standard deduction by refusing to conform to the 2003 law.

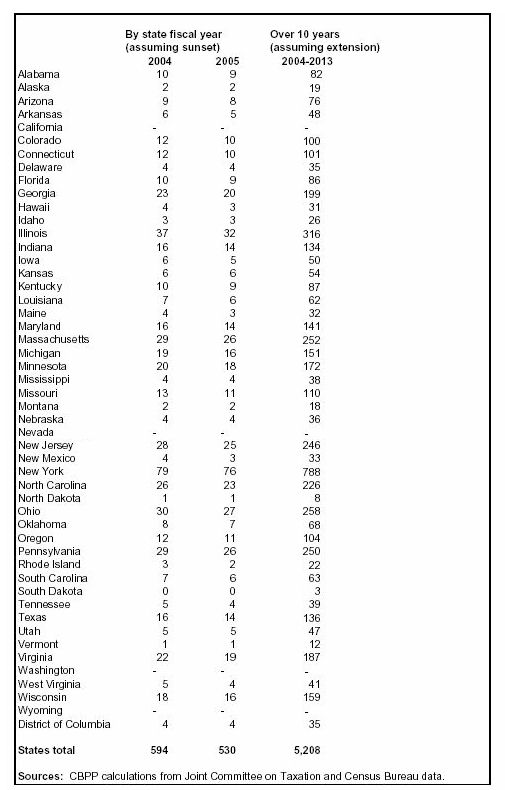

State-by-state Impacts of Bonus Depreciation and Section 179 Conformity

Tables 2 and 3 provide state-by-state estimates of the impact of conforming to the new bonus depreciation rules (for those states already conforming to the previous bonus depreciation rules) and to the Section 179 expensing rules. They should be considered approximate, order-of-magnitude estimates, because no 50-state modeling capacity exists to estimate impacts with any precision.

All states with income taxes, except

The bonus depreciation estimates in

Table 3 are for those states that conform under current law to federal bonus

depreciation rules for 2004, including

In these tables, any possible SFY2003 impacts are rolled into the SFY 2004 figures, since SFY2003 is almost over in most states.

Note that under the conference agreement, the bonus depreciation provision would expire at the end of calendar year 2004 and the Section 179 provision would expire at the end of calendar year 2005. It is unclear whether Congressional and Administration leaders intend to extend these provisions. In Tables 2 and 3, the 2004 and 2005 figures are based on the assumption that provisions expire as scheduled. The 10-year figures assume that the provisions are extended over 10 years.

Table 2

Approximate Impacts of Federal “Section 179 Expensing”

Provisions on State Tax Revenue

|

Table 3 |

||||

|

|

By state fiscal year |

Over 10 years |

||

|

|

(assuming sunset) |

(assuming extension) |

||

|

Affected states |

2004 |

2005 |

2004-2013 |

|

|

|

100 |

27 |

921 |

|

|

|

70 |

35 |

768 |

|

|

|

56 |

28 |

611 |

|

|

|

241 |

121 |

2,635 |

|

|

|

40 |

20 |

437 |

|

|

|

67 |

34 |

738 |

|

|

|

52 |

26 |

571 |

|

|

|

78 |

45 |

991 |

|

|

|

18 |

9 |

196 |

|

|

|

33 |

17 |

360 |

|

|

|

106 |

97 |

2,122 |

|

|

|

12 |

6 |

127 |

|

|

|

19 |

10 |

213 |

|

|

|

70 |

35 |

767 |

|

|

|

36 |

18 |

390 |

|

|

|

3 |

2 |

35 |

|

|

|

52 |

26 |

572 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

States total |

1,053 |

556 |

12,454 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: CBPP calculations from Joint Committee on Taxation and Census Bureau data. |

||||

End Notes:

[1] A small number of states allow a deduction against state taxes for federal tax payments. In these states, the reductions in tax rates and other provisions would tend to increase state tax revenue, partially offsetting the state revenue losses described below.