- Home

- Tax Foundation Estimates Of State And Lo...

Tax Foundation Estimates of State and Local Tax Burdens are not Reliable

Summary

In April 2006, the Tax Foundation is expected to release its annual report on “Tax Freedom Day,” which it describes as the day when “Americans will finally have earned enough money to pay off their total tax bill for the [current] year.” For each state, the report will show the Tax Foundation’s estimate of state and local taxes paid by residents of that state as a share of residents’ total incomes and each state’s ranking by that measure. The estimates are shown calculated to one-tenth of one percentage point.

The apparent timeliness and precision of the Tax Foundation’s estimates are likely to attract the attention of policymakers and the media, who may use the rankings to make claims about a given state’s “tax burden” relative to those in other states. But what the Tax Foundation is unlikely to acknowledge – save in the methodology section at the end of its report, and even there only indirectly – is that its state and local findings do not reflect actual total tax collections for that year or for the previous year. Rather, the findings are estimates and projections, largely derived from years-old data and from national samples that were never intended to be used for state-by-state estimates, and calculated using a methodology that never has been formally published or subject to outside review.

This report shows the degree to which their initial projections have been erroneous, and thus potentially misleading to policymakers.

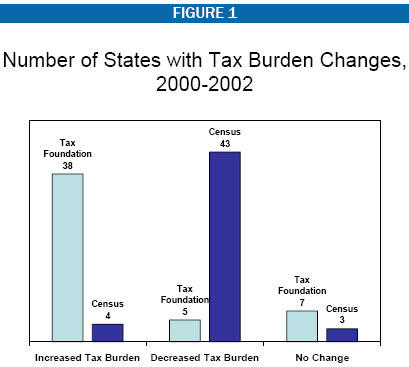

- For example, in their 2002 report the Tax Foundation claimed that tax burdens had risen since 2000 in 38 states. But three years later, it issued a revision that showed only eight states had higher tax burdens in 2002 than in 2000 — not the 38 states it had initially claimed. (Data from the Census Bureau shows that the tax burden had risen between 2000 and 2002 in only four states.)

- When the Tax Foundation’s initial report was released in April 2002, a number of states were debating whether to address their budget shortfalls with additional tax revenue or through budget cuts. Tax Foundation “information” that tax burdens already had been rising in a state over the past two years could have influenced the debate. But, as the Tax Foundation’s own revision showed, the initial “information” wasn’t true. So any policy implications that were drawn from the Tax Foundation’s report were unfounded.

The Tax Foundation’s Defense of Its Inaccurate

State and Local Tax Estimates

In a response to these criticisms posted to the Tax Foundation web site March 20, 2006, the Tax Foundation does not deny the substantive finding that actual state and local tax levels and rankings frequently turn out to be very different than the Tax Foundation’s initial predictions. Rather, the Tax Foundation asserts that its report gives the news media, policymakers, and general readers ample information to make an informed decision on whether to take the results seriously or not.

But there is reason to believe that the Tax Foundation report does not adequately forewarn the reader of the uncertainty of its estimates. For example, the words “forecast” and “estimate” do not appear in the 2005 report until the “methodology” section of the report, which begins on page 15 of the 16-page report. More significantly, the Tax Foundation has not published a formal analysis of whether its model provides accurate forecasts. Nor does the Tax Foundation provide in any reasonably accessible form a way for readers themselves to compare forecasts with actual results.

This approach stands in sharp contrast to the approach used by other researchers who publish estimates. For example, the Tax Foundation compares its report to the data published by the highly regarded U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis as examples of estimates that are regularly revised. But BEA’s approach is distinctly different from the Tax Foundation’s. BEA makes clear throughout its press materials and reports that its figures are estimates. It publishes extensive, detailed explanations of how and why their estimates are revised. (Some BEA revisions reflect improved data, but others reflect definitional changes.) The Tax Foundation does neither of those things.

The Tax Foundation’s rankings of state tax burdens also tend to be flawed.

- The Tax Foundation reported in 2002 that Arkansas had the 7th highest state and local tax burden. In 2005, when the Tax Foundation released revised rankings for 2002, it reported Arkansas as having the 27th highest state and local tax burden, a revision of 20 places. New Mexico’s ranking was revised downward from 12th to 33rd, a drop of 21 places, and Delaware’s ranking fell 22 places.

- Other states also had their rankings revised. Between the 2002 Tax Foundation report and the 2005 revision, the ranking by state and local tax burden of 24 states changed by at least five places, and in 13 states the rankings changed by at least 10 places.

The estimates the Tax Foundation puts out every April often turn out to be misleading, because it is impossible to do what they claim they are doing; no one could estimate the current year’s taxes relative to income for each state and its numerous local units of government all over the country to the point of being able to rank them with any reasonable degree of confidence. In April, when the Tax Foundation releases its estimates, most taxes for the calendar year have not yet been collected. Nor is it possible to know what the path of income growth will be for the year. There is no way that the Tax Foundation’s numbers can be anything but speculative. The Tax Foundation does not deny this fact. But nowhere in its Tax Freedom Day report does the Tax Foundation discuss the likelihood that its speculations may turn out to be wrong.

The only definitive information on state and local tax collections is compiled by the Census Bureau. But the Census Bureau takes time to compile data on actual state and local taxes; the report for a given year typically is released more than two years later. Once the Census data is completed it can be compared to the income information prepared by the Commerce Department — which also isn’t final for a substantial period of time — to determine “tax burden.”[1] For the 2002 data discussed above, final information was not available until August 2004.[2]

It is worth noting that there are some conceptual differences between Tax Foundation and Census calculations of tax levels. For example, the Tax Foundation attempts to measure taxes by calendar year, while Census data are based on fiscal year. More significantly, the Tax Foundation attempts to measure taxes paid by residents of each state, including taxes paid to other states, while the Census Bureau measures taxes collected by state and local governments within each state, including from non-residents. Thus the Tax Foundation measures the effect of the tax policies of all the states collectively on the residents of each state, while the Census measures the effect of the tax policies enacted in each state on its own residents. As a result, even if it were reliably accurate, the Tax Foundation data would still be less useful for understanding the links between tax levels and state policy.

State Tax Freedom Day is Misleading

The Tax Foundation's reports include a list of the dates described as representing "Tax Freedom Day" for each state. In addition to the problem of unreliable estimates highlighted in this report, a number of other serious flaws mar the Tax Foundation's estimates of total tax burdens on state residents.

- About two-thirds of the tax burdens in the Tax Foundation calculations are federal tax burdens. The amount of federal taxes paid by the residents of a state thus has a large impact on that state’s “Tax Freedom Day.” But the Tax Foundation’s analysis of federal taxes is problematic. Its use of average taxes substantially overstates the federal tax burden of the vast majority of families; its estimates are at odds with more authoritative sources such as the Congressional Budget Office. In addition, its methodology is flawed because it counts taxes paid on capital gains but ignores the capital gains income on which these taxes are paid, and counts as taxes a number of non-tax items.* Because of these problems, the Tax-Freedom-Day figures for each state — which include the federal numbers — also substantially exaggerate the tax burdens of middle-class families.

- Because the federal income tax system is progressive, states with relatively wealthy residents — those with higher-than-average per capita personal income — end up under the Tax Foundation’s methodology with a higher federal tax burden than other states. The fact that one state has higher-income residents than another state has nothing to do with the level of state and local taxes in a state. Yet by trumpeting state-level Tax Freedom Days that differ across the states, the Tax Foundation may give the misleading impression that differences in burdens imposed by state and local taxes account for the differences across states in the Tax Foundation’s “average tax burden.”

- As noted in this report, the Tax Foundation uses a procedure to allocate corporate, severance, and tourism taxes based on the location of the consumers who purchase products that businesses sell (adjusted for taxes that tourists pay). This is likely to lead to further misimpressions about the role of a state’s tax policies on the tax burdens its residents are said to face. For example, when Alaska collects taxes from oil companies based on the amount of oil they produce in the state, the Tax Foundation does not count those taxes as part of Alaska’s revenue. Rather, they add those taxes to the tax burden in the states where oil is consumed. Maine residents consume a significant amount of fuel and so get allocated a large share of these Alaska taxes. Yet state legislators in Maine cannot have much impact on the level of taxes that Alaska or other oil-producing states levy on oil.

As a result, the Tax Foundation’s proclamations of state Tax Freedom Days are misleading and do little to inform legitimate debates over levels of state and local taxes and the services those taxes support.

*For a fuller description of the problems in computing the federal tax burden, see Joel Friedman, Aviva Aron-Dine, and Robert Greenstein, Tax Foundation Figures Do Not Represent Middle-Income Tax Burdens, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 10, 2006.

(13pp.)

End Notes

[1] Note that the Census Bureau definition of tax burden, taxes as a percent of personal income, shares with the Tax Foundation one of the flaws described in the box on page 4. It counts taxes paid on capital gains income, but does not count the capital gains income on which those taxes were paid. This is because the Commerce Department’s National Income and Product Accounts — from which the measure of personal income as well as the income measure used by the Tax Foundation are derived — do not include capital gains income.

[2] The 2002 data on state and local taxes, by state, remain the most recent available from the Census Bureau, although 2004 figures are scheduled to be released in late April or May 2006.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise

Areas of Expertise