|

Updated May 9, 2008

TAX CUTS: MYTHS AND REALITIES

Since 2001, the Administration and Congress have enacted a wide array of tax cuts, including reductions in individual income tax rates, repeal of the estate tax, and reductions in capital gains and dividend taxes. Nearly all of these tax cuts are scheduled to expire by the end of 2010. Making them permanent would cost about $4.4 trillion over the next decade (when the cost of additional interest on the federal debt is included). (https://www.cbpp.org/1-31-07tax.htm)

Because important decisions about these tax policies must be made in the next few years, it is essential to understand their effects on deficits, the economy, and the distribution of income. Supporters of the tax cuts have sometimes sought to bolster their case by understating the tax cuts’ costs, overstating their economic effects, or minimizing their regressivity. Here, we address some of the myths heard most frequently in recent tax-cut debates. (For a discussion of myths specific to the estate tax debate, see https://www.cbpp.org/pubs/estatetax.htm. For a discussion of issues surrounding the Alternative Minimum Tax, see https://www.cbpp.org/2-14-07tax.htm.)

Tax Cuts and Deficits

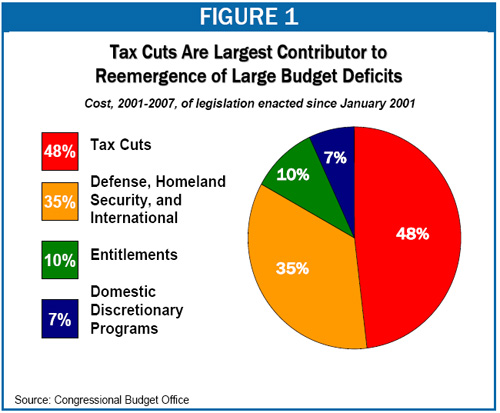

Congressional Budget Office data show that the tax cuts have been the single largest contributor to the reemergence of substantial budget deficits in recent years. Legislation enacted since 2001 added about $3.0 trillion to deficits between 2001 and 2007, with nearly half of this deterioration in the budget due to the tax cuts (about a third was due to increases in security spending, and about a sixth to increases in domestic spending). Yet the President and some Congressional leaders decline to acknowledge the tax cuts’ role in the nation’s budget problems, falling back instead on the discredited nostrum that tax cuts “pay for themselves.”

Myth 1: Tax cuts “pay for themselves.”

“You cut taxes and the tax revenues increase.” — President Bush, February 8, 2006

“You have to pay for these tax cuts twice under these pay-go rules if you apply them, because these tax cuts pay for themselves.” — Senator Judd Gregg, then Chair of the Senate Budget Committee, March 9, 2006

Reality: A study by the President’s own Treasury Department confirmed the common-sense view shared by economists across the political spectrum: cutting taxes decreases revenues.

Proponents of tax cuts often claim that “dynamic scoring” — that is, considering tax cuts’ economic effects when calculating their costs — would substantially lower the estimated cost of tax reductions, or even shrink it to zero. The argument is that tax cuts dramatically boost economic growth, which in turn boosts revenues by enough to offset the revenue loss from the tax cuts.

But when Treasury Department staff simulated the economic effects of extending the President’s tax cuts, they found that, at best, the tax cuts would have modest positive effects on the economy; these economic gains would pay for at most 10 percent of the tax cuts’ total cost. Under other assumptions, Treasury found that the tax cuts could slightly decrease long-run economic growth, in which case they would cost modestly more than otherwise expected. (https://www.cbpp.org/7-27-06tax.htm)

The claim that tax cuts pay for themselves also is contradicted by the historical record. In 1981, Congress substantially lowered marginal income-tax rates on the well off, while in 1990 and 1993, Congress raised marginal rates on the well off. The economy grew at virtually the same rate in the 1990s as in the 1980s (adjusted for inflation and population growth), but revenues grew about twice as fast in the 1990s, when tax rates were increased, as in the 1980s, when tax rates were cut. Similarly, since the 2001 tax cuts, the economy has grown at about the same pace as during the equivalent period of the 1990s business cycle, but revenues have grown far more slowly. (https://www.cbpp.org/3-8-06tax.htm)

Some argue that, even if most tax cuts do not pay for themselves, capital gains tax cuts do. But, in reality, capital gains tax cuts cost money as well. After reviewing numerous studies of how investors respond to capital gains tax cuts, the Congressional Budget Office concluded that “the best estimates of taxpayers’ response to changes in the capital gains rate do not suggest a large revenue increase from additional realizations of capital gains — and certainly not an increase large enough to offset the losses from a lower rate.” That’s why CBO, the Joint Committee on Taxation, and the White House Office of Management and Budget all project that making the 2003 capital gains tax cut permanent would cost about $100 billion over the next ten years. (https://www.cbpp.org/policy-points4-18-08.htm)

Myth 2: Even if the tax cuts reduced revenues initially, they boosted revenues and lowered deficits in 2005 to 2007.

“Some in Washington say we had to choose between cutting taxes and cutting the deficit… Today’s numbers [the updated 2006 budget projections] show that that was a false choice. The economic growth fueled by tax relief has helped send our tax revenues soaring.” — President Bush, July 11, 2006

Reality: Robust revenue growth in 2005-2007 has not made up for extraordinarily weak revenue growth over the previous few years.

When discussing revenue growth since the enactment of the tax cuts, Administration officials typically focus only on revenue growth since 2004. This provides a convenient starting point for their arguments, as it sets a very low bar. In 2001, 2002, and 2003, revenues fell in nominal terms (i.e. without adjusting for inflation) for three straight years, the first time this has occurred since before World War II. Measured as a share of the economy, revenues in 2004 were at their lowest level since 1959. Given this historically low starting point, it is not surprising that revenues have recovered since then. Supporters of the tax cuts selectively cite revenue growth over just the past three years to argue that the tax cuts fueled increases in revenues.

|

Table 1:

Total Real Per-Capita Revenue Growth in 22 Quarters after the Last Business Cycle Peak |

| 2001-2007 |

1.7% |

| Average for All Previous Post-World War II Business Cycles |

12.0% |

| 1990s Business Cycle (Following Tax Increases) |

16.2% |

Even taking into account the growth in revenues in fiscal years 2005-2007, total revenues have just barely increased over the 2001-2007 business cycle, after adjusting for inflation and population growth. (The business cycle began in March 2001, when the 1990s business cycle hit its peak and thereby came to an end.) In contrast, six and a half years after the peak of previous post-World War II business cycles, real per-capita revenues had increased by an average of 12 percent, and in the 1990s, real per-capita revenues were up 16 percent (see Table 1). Revenues in 2007 were still more than $250 billion short of where they would have been had they grown at the rates typical in other recoveries.

Further, while the Administration has credited the tax cuts with the drop in the fiscal year 2007 deficit to “only” $162 billion, the 2007 budget would have been in surplus were it not for the tax cuts. Based on Joint Committee on Taxation estimates, the total 2007 cost of tax cuts enacted since January 2001 was $300 billion (taking into account the increased interest costs on the debt that have resulted from the deficit financing of the tax cuts). This means that even with the spending for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the federal budget would have been in surplus in 2007 if the tax cuts had not been enacted, or if their costs had been offset. While supporters of these tax cuts claim that their positive economic effects have lowered their cost, the non-partisan Congressional Research Service found in a September, 2006 report that “at the current time, as the stimulus effects have faded and the effect of added debt service has grown, the 2001-2004 tax cuts are probably costing more than their estimated revenue cost.”

Looking out over the next several decades, when deficits are projected to be far larger (because of the impact on the budget of the continued rise in health care costs and the retirement of the baby boomers), the tax cuts, if extended, will still be a major contributor to the nation’s fiscal problems. (https://www.cbpp.org/1-29-07bud.htm) To put the long-run cost of the tax cuts in perspective, the 75-year Social Security shortfall, about which the President and Congressional leaders have expressed grave concern, is less than one-third the cost of the tax cuts over the same period. (https://www.cbpp.org/3-31-08socsec.htm)

Tax Cuts and the Economy

A consistent finding in the academic literature about the effects of tax cuts on the economy is that these effects are typically modest. In the short run, well-designed tax cuts can help to boost an economy that is in a recession. In the longer run, well-designed tax cuts can have a modest positive impact if they are fully paid for. For example, the recent Treasury analysis found that if the President’s tax cuts were made permanent and the costs of the tax cuts were paid for by reductions in programs, economic growth would increase by a few hundredths of one percentage point annually. Meanwhile, studies by economists at the Joint Committee on Taxation, the Congressional Budget Office, the Brookings Institution, and elsewhere have found that if tax cuts are not paid for with spending reductions, they are likely to have modest negative effects on the economy over time, because of the negative effects of the increased deficits. Tax-cut proponents often claim that the economy will be badly damaged if the tax cuts are not extended; these claims are without foundation.

Myth 3: The economy has grown strongly over the past several years because of the tax cuts.

“The main reason for our growing economy is that we cut taxes and left more money in the hands of families and workers and small business owners.” — President Bush, November 4, 2006

Reality: The 2001-2007 economic expansion was sub-par overall, and job and wage growth were anemic.

Members of the Administration routinely tout statistics regarding recent economic growth, then credit the President’s tax cuts with what they portray as a stellar economic performance. But as a general rule, it is difficult or impossible to infer the effect of a given tax cut from looking at a few years of economic data, simply because so many factors other than tax policy influence the economy. What the data do show clearly is that, despite major tax cuts in 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, and 2006, the economy’s performance between 2001 and 2007 was from stellar.

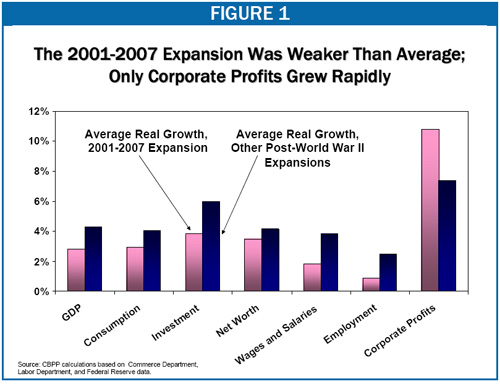

Growth rates of GDP, investment, and other key economic indicators during the 2001-2007 expansion were below the average for other post-World War II economic expansions (see Figure 2). Growth in wages and salaries and non-residential investment was particularly slow relative to previous expansions, and, while the Administration boasts of its record on jobs, employment growth was weaker in the 2001-2007 period than in any previous post-World War II expansion. (https://www.cbpp.org/8-9-05bud.htm)

Median income among working-age households, meanwhile, fell during the expansion. Census data show that among households headed by someone under age 65, median income in 2006, adjusted for inflation, was $1,300 below its level during the 2001 recession. Similarly, the poverty rate and the share of Americans lacking health insurance were higher in 2006 than during the recession. (https://www.cbpp.org/8-28-07pov.htm)

Myth 4: Even if economic growth and the job market were weak during the early stages of the recovery, the capital gains and dividend tax cuts turned the economy around in 2003.

“Since the tax rates on capital gains and dividends were reduced in 2003, we have seen strong steady economic growth, resulting in higher employment.” — Representative Bill Thomas, then Chair of the Ways and Means Committee, May 17, 2006

Reality: The available evidence indicates that the capital gains and dividend tax cuts were not the cause of improvement in the economy in 2003.

The President and other tax-cut advocates have credited the capital gains and dividend tax cuts with the fact that the economy performed better between 2003 and 2007 than in the earlier part of the expansion. But they have produced no evidence to support their leap from correlation (the tax cuts coincided with improvement in the economy) to causation (the claim that the tax cuts caused the improvement). Furthermore, they have ignored evidence that indicates there was little or no causal connection.

Notably, informed observers such as Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke (then a Federal Reserve Board governor) were predicting improvement in the economy before the 2003 tax cuts were enacted. In addition, supporters of enacting these tax cuts, such as conservative economist Gary Becker, acknowledged at the time that, whatever the tax cuts’ long-run effects on economic growth, they would not boost the economy in the short term.

Also striking is the fact that the expansion of the 1990s followed a pattern similar to the 2001-2007 expansion, especially with respect to investment growth (which the dividend and capital gains tax cuts were supposed to encourage). Investment was weak in the early 1990s and then began to improve about two years into the expansion. But in the 1990s, that improvement — which was greater than the improvement in the early 2000s — coincided with a tax increase (see Figure 3). If one accepts the notion that any economic change that follows a tax change must have been caused by the tax change, one would have to conclude that tax increases promote stronger investment growth than tax cuts. The more reasonable conclusion, of course, is that weak recoveries eventually tend to return to historical norms.

Moreover, even growth since 2003 has been less than impressive. GDP, wage and salary, and employment growth have remained below average for a post-World War II recovery, while growth in non-residential investment has only matched the historical norm. (https://www.cbpp.org/7-10-07tax.htm)

Myth 5: Extending the tax cuts is important for the economy’s long-run health.

“To keep this economy growing and delivering prosperity to more Americans, we need leaders in Washington who understand the importance of letting you keep more of your money, and making the tax relief we delivered permanent.” — President Bush, October 28, 2006

Reality: Extending the tax cuts without paying for them would be more likely to reduce economic growth over the long run than to increase it.

Researchers at the Joint Committee on Taxation, the Congressional Budget Office, and the Brookings Institution have all found that large unpaid-for tax cuts reduce economic growth over the long run. For example, a study by Brookings Institution economist William Gale and then-Brookings economist (now CBO director) Peter Orszag concluded that making the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts permanent without offsetting their cost would be “likely to reduce, not increase, national income over the long run.” Similarly, in a study in which it examined the economic effects of reductions in individual and corporate tax rates and an increase in the personal exemption, the Joint Committee on Taxation found, “Growth effects eventually become negative without offsetting fiscal policy [i.e. without offsets] for each of the proposals, because accumulating Federal government debt crowds out private investment.” (https://www.cbpp.org/3-19-07bud.htm)

The reason behind these results is that, even if tax cuts have modest positive effects on work and savings decisions, those effects are outweighed by the negative consequences of higher budget deficits. In claiming that tax cuts will boost savings, investment, and GDP growth, supporters often seem to forget that national savings has two components: private and public (i.e., government) savings. Tax cuts could positively affect private savings, although, as the Congressional Research Service has noted, studies have failed to find large effects. But when the federal government runs a deficit, it pays for the deficit by borrowing money from the private sector, which reduces national savings. By adding to deficits, unpaid-for tax cuts thus generally reduce national savings.

Making the tax cuts permanent would add about $4.4 trillion to deficits over the next decade, when the additional interest costs on the national debt are included. The resulting decrease in national savings would mean fewer funds available for investment, reducing the size of the capital stock (the total supply of equipment, buildings, and other productive capital in the economy). With less capital available, future workers would be less productive, and as a result, national income over the long run would be lower than it otherwise would be. (As discussed above, even if paid for, the positive effects of the tax cuts on the economy would be quite small. Moreover, paying for the tax cuts with spending cuts would require deep cuts in federal programs, as discussed below in Myth 8.)

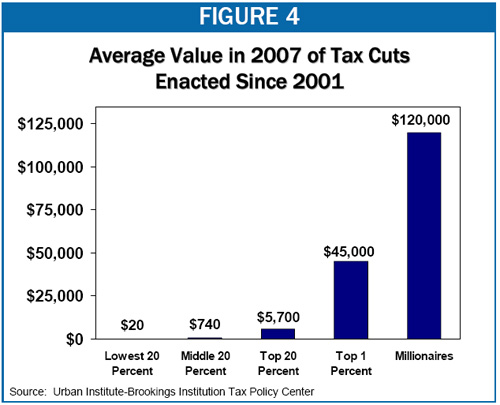

Tax Cuts and Fairness

The tax cuts enacted in recent years have gone disproportionately to high-income Americans. In 2007, the 0.3 percent of households with incomes above $1 million received about $120,000, on average, from the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts, according to estimates by the Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center. In contrast, households in the middle of the income spectrum received tax cuts averaging $740. The Tax Policy Center estimates also show that the tax cuts represent a larger fraction of income for high-income households than for low- or middle-income households, a clear indication of these tax cuts’ regressivity.

Myth 6: The tax cuts have made the tax system more progressive.

“The President’s tax cuts have made the tax code more progressive, which also narrows the difference in take-home earnings.” — Council of Economic Advisers Chair Edward Lazear and Katherine Baicker, then a member of the Council of Economic Advisers, May 8, 2006

Reality: The tax cuts have made the distribution of take-home pay more unequal — at a time when inequality in before-tax income has also increased.

A progressive tax change, like a progressive tax system, is one that reduces inequality. In Lazear and Baicker’s terms, it is a tax cut that “narrows the difference in take-home earnings.” Take-home earnings consist of a person’s income after taxes have been paid. So a progressive tax cut would be one that raised after-tax incomes for those at the bottom of the income spectrum by a larger percentage than for those at the top, increasing their share of total take-home pay.

The President’s tax policies, however, have widened the differences in take-home pay between high- and low- and middle-income households, according to Tax Policy Center estimates. When the tax cuts are fully in effect, households with incomes above $1 million will receive tax cuts equivalent to an increase of 7.5 percent in their after-tax income. Households in the middle of the income spectrum will receive tax cuts equal to only 2.3 percent of their income. And households in the bottom quintile will gain by less than one percent.

Put another way, households with incomes over $1 million will hold a larger fraction of total U.S. after-tax income than they would have received without the tax cuts, while households in the middle and bottom quintiles will hold a smaller share. The tax cuts thus have widened, rather than narrowed, income gaps, making them regressive. (https://www.cbpp.org/3-11-08tax.htm)

While comparisons of percent changes in after-tax earnings measure the tax cuts’ effect on the distribution of income, the dollar values of the tax cuts received by different income groups are also relevant to evaluating these tax cuts’ overall fairness. For example, over the next ten years (assuming the tax cuts are extended), more than $800 billion will be spent on tax cuts for the 0.3 percent of households with incomes above $1 million, with these tax cuts averaging over $150,000 per-household annually. At issue is whether this represents an appropriate use of scarce public resources. (https://www.cbpp.org/2-4-08tax.htm)

The skewed distribution of the tax cuts is of particular concern given that, since 2001, gaps in before-tax income have widened. As of 2006, the highest-income 1 percent of households held a larger share of total pre-tax income that in any year since 1928. (https://www.cbpp.org/3-27-08tax2.htm).

Myth 7: The tax cuts have made the tax system more fair to small business owners.

“We cut the taxes on the small business owners… [I]t makes sense to let small businesses keep more of the money they make.” — President Bush, April 13, 2006

Reality: The President’s tax cuts affect small business owners much as they affect the population as a whole: they provide large gains to those with high incomes and little benefit to others.

One major benefit the President’s tax cuts have supposedly offered small business owners is the reduction in the top individual income tax rate, from 39.6 percent to 35 percent. Because small business owners pay individual income tax on their business income, the Administration contends that they are disproportionate beneficiaries of the rate reduction.

But a Tax Policy Center analysis found that only 1.3 percent of filers with small business income are subject to the top income tax rate and so benefit from lowering it. Moreover, these households hardly conform to the popular image of a small business owner: they derived, on average, less than a third of their total income from a small business. (https://www.cbpp.org/3-21-07tax.htm)

An even more muddled mythology surrounds the issue of small business owners and the estate tax. Despite oft-repeated claims that the estate tax has dire consequences for family farms and small businesses, there is in fact very little evidence that it has any significant impact on these groups. An analysis by the Congressional Budget Office found that exceedingly few farms and small businesses owe any estate tax. Indeed, the American Farm Federation acknowledged to the New York Times that it could not cite a single example of a farm having to be sold to pay estate taxes.

Myth 8: Even if high-income taxpayers have received the largest gains from the tax cuts, taxpayers across the income spectrum have benefited.

“President Bush’s tax relief benefits all taxpayers.” — White House Fact Sheet, May 11, 2006

Reality: Taking into account the fact that their costs eventually must be paid for, most American families likely will lose from the tax cuts over the long run.

Claims that all taxpayers are winners from the President’s tax cuts rest on the false assumption that Congress and the President can provide trillions of dollars in tax cuts without anyone ever footing the bill. As noted in Myth 1, the tax cuts so far have been financed by deficits, and most proposals to extend them include no measures to offset their costs. In the long run, however, it is widely recognized that deficit-financed tax cuts eventually must be paid for. As former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan warned, “If you’re going to lower taxes, you shouldn’t be borrowing essentially the tax cut. And that over the long run is not a stable fiscal situation.” Simply stated, funds that are borrowed must eventually be paid back.

When the tax cuts ultimately are paid for, the costs will be very large and the choices difficult, especially given the bleak long-term deficit outlook. Once the tax cuts are fully in effect, their annual cost will be equal, in today’s terms, to the entire annual budgets of the Departments of Education, Homeland Security, Housing and Urban Development, Veterans’ Affairs, State, Energy, and the Environmental Protection Agency combined. If the tax cuts are extended without offsets, balancing the budget in 2012 will require cutting Social Security benefits by 36 percent, cutting defense by 40 percent, cutting Medicare by 55 percent, or cutting every other program other than Social Security, defense, Medicare, and homeland security (including education, medical research, border security, environmental protection, veterans’ programs, and programs to assist the poor) by an average of almost one-fourth. For most Americans, keeping the tax cuts at the cost of implementing any of the above options would be a bad bargain.

Even if the tax cuts’ costs are eventually paid for through a more balanced package of spending reductions and progressive tax increases, data from the Tax Policy Center show that, on average, the bottom four-fifths of households will lose more than they gain from the combination of tax cuts and the financing for them. That is, once the need to pay for the tax cuts is taken into account, the 2001 and 2003 “tax cuts” are best seen as net tax cuts for the top 20 percent of households, as a group, financed by net tax increases or benefit reductions for the remaining 80 percent of households, as a group. (https://www.cbpp.org/6-2-04tax.htm) |