THE AUGUST UNEMPLOYMENT RATE MASKS THE SEVERITY OF THE

DOWNTURN

AND THE PROBLEMS OF THOSE EXHAUSTING THEIR UNEMPLOYMENT BENEFITS

By

Wendell Primus and

Jessica Goldberg

| PDF of this report |

|

Related report: Number of Workers Exhausting Federal Unemployment Insurance Benefits Will Reach an Estimated 1.5 Million by the End of September and Exceed Levels in the Last Recession Additional related reports |

| If you cannot access the files trough the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

Some have suggested that the current unemployment rate — which has been hovering close to six percent and was 5.7 percent in August 2002 — indicates the recession is quite mild and is harming only a modest number of workers. One implication of this view is that strengthening and extending the federal Temporary Emergency Unemployment Compensation Program, the temporary program providing federally-funded unemployment insurance (UI) benefits to workers that run out of regular state UI benefits, is not necessary.

That assessment is mistaken. Although by some commonly used measures the consequences of the recent downturn have not been as severe as the consequences of the recession of the early 1990s, by certain other measures the recession that began last year has hit workers just as hard as the recession of the early 1990s. In fact, by some important measures, such as the actual number of workers whose federally-funded unemployment benefits are running out before they are able to find a new job — this recession has hit workers harder than the last recession. This analysis also examines other reasons why not too much should be read into the downward tick in the unemployment rate in August.

Changes in Unemployment

The most accurate way to evaluate a recession’s impact on unemployment is to examine the increase in unemployment during the recession, rather than the overall unemployment rate. Stated somewhat differently, it is the increase in unemployment that measures the degree to which the economic situation of workers has worsened as a consequence of a downturn. By most measures of unemployment, the increase in unemployment during this recession is similar to or exceeds the increase during the recession of the early 1990s.

The official seasonally adjusted unemployment rate issued by the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) includes anyone who is classified as unemployed, regardless of the reason for their unemployment. The official unemployment data show substantial increases in both the number of unemployed and the unemployment rate since the recession began in March 2001; these increases are similar to the increases that occurred in the early 1990s recession.

- BLS data indicate that there were 2.3 million more unemployed workers in August 2002 than in February 2001, the month before the recession began. Some 18 months into the recession of the early 1990s, the number of unemployed had increased by 2.6 million, a figure that is only modestly larger.

- Comparing average unemployment over two three-month periods can provide a better picture of changes in unemployment than comparing two single months, since three-month averages incorporate more information and smooth out one-month aberrations. Comparing the three months prior to the start of the current recession in March 2001 to the latest three months for which information is available shows that unemployment grew by 2.5 million workers. During this period, the average three-month unemployment rate grew from 4.1 percent to 5.8 percent, an increase of 1.7 percentage points.

- Some 18 months into the recession of the early 1990s, the average number of unemployed over a three-month period had grown by 2.3 million workers compared to the three months just prior to the recession. During this period the average three-month unemployment rate grew from 5.3 percent to 7.1 percent, an increase of 1.8 percentage points. Thus, comparing the figures from the two downturns, the actual increases in the number of unemployed persons and increases in the unemployment rate are similar.

- It took about 24 months in the 1990 recession for unemployment to peak. Over this period, the three-month average unemployment rate increased 2.2 percentage points. It is too soon to tell whether the unemployment rate has yet peaked as a consequence of the recent downturn.

A second set of indicators comes from the information compiled for the unemployment insurance program. The measure of unemployment used here is the insured unemployment rate (IUR), which measures the number of workers that are receiving regular, state-funded unemployment insurance benefits. One advantage of this measure is that since, in most states, an unemployed worker must have a minimum level of earnings and weeks of work history to qualify for unemployment benefits, the IUR measures unemployment among experienced workers with a significant labor force attachment. By contrast, the overall unemployment rate figures also include people who have not recently been working or looking for work, such as new entrants and re-entrants into the labor market.

The proportion of workers receiving regular unemployment benefits has actually risen more during this recession than it did in the last recession.

- Because most unemployment insurance data are not seasonally adjusted and because averaging three months of data is technically better, the remainder of this analysis uses three-month averages, centered two years apart.[1]

- Between June - August 1990 and June - August 1992, the insured unemployment rate increased from 2.4 percent to 3.1 percent, an increase of 0.7 percentage points. During the period from June - August 2000 and June - August 2002, the average three-month IUR increased from 1.7 percent to 2.8 percent, a 1.1 percentage point increase. The IUR thus has increased more during the current slump than it did in the early 1990s recession. This indicates that for experienced workers, the impact of this recession has been somewhat more severe.

Although the IUR is a better measure of unemployment among experienced workers than the official unemployment rate, it has several defects itself.[2] Of special note here, the IUR does not take into account experienced workers who have been unemployed for such a long period of time that they have exhausted their regular unemployment benefits, which typically end after 26 weeks or less. These workers do not count as unemployed in the IUR. Thus, unemployed workers who are receiving additional weeks of federally funded unemployment benefits or who have exhausted their benefits — that is, workers who presumably have had the most trouble finding a job and whose economic situation is especially perilous — are not counted by this measure.

As a result, it is also worth examining a third measure of unemployment, the Adjusted Insured Unemployment Rate (AIUR), which modifies the IUR so that it also incorporates a measurement of those who have exhausted their regular unemployment benefits.

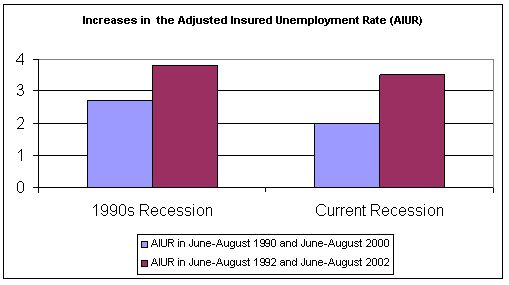

- The AIUR has increased more sharply in the past two years than it did during a comparable two-year period in the early 1990s recession.

- The AIUR increased by 1.5 percentage points between June - August 2000 and June - August 2002.[3] During a comparable two-year period of the last recession, it rose by 1.1 percentage points. (See Figure below.)

- In 36 states, the AIUR has increased more in this recession than in the last recession.

- In this recession, AIURs have increased by two percentage points or more in five states: Massachusetts, Michigan, North Carolina, Oregon, and Washington. In the prior recession, only one state had an AIUR increase of two percentage points or more.

- AIURs have increased by one percentage point or more in 36 states in this recession, compared to 23 states in the prior recession.

In summary, data from the unemployment insurance system that reflect the impact of the downturn on experienced workers show somewhat greater increases in unemployment in this recession than in the prior recession.

Workers Exhausting Unemployment Insurance Benefits

The importance of the recent unemployment increase is magnified by the recent increase in the number of workers that are exhausting their weeks of unemployment insurance benefits without finding a job. These workers have significant work experience but are unable to find a job before their benefits expire. The exhaustee data show that, in some respects, current labor market problems are worse than those in the early 1990s.

- The number of unemployed workers whose regular state-funded unemployment benefits ran out before they were able to find a job was 1,185,000 larger in the six-month period from February - July 2002 (the latest six-month period for which these data are available) than in the six-month period from February - July 2000. (Due to seasonal fluctuations, a six-month period is used here and is compared to the same six-month period from two years ago.) This 1,185,000 increase in the number of workers exhausting benefits substantially exceeds the increase in the comparable period of the recession of the early 1990s.[4]

- The total number of exhaustions also is greater in this recession than in the last: 2.3 million workers have exhausted their regular UI benefits over the past six months, as compared to 2.0 million for a six-month period at a comparable point in the last recession.[5] Nationally, the number of exhaustions has doubled in the past two years.

- Data for each state on the number of

exhaustions during the past six months are shown in the attached table.

The number of exhaustions by state in the comparable six-month period of 2000

also is shown, as is the increase by state in the number of exhaustions

between the February - July 2000 period and the February - July 2002 period.

The table also provides state-by-state data on the increase in exhaustions

during a comparable period in the recession of the early 1990s.

For example, in Alabama, 24,811 workers exhausted their regular state-funded benefits during the February – July 2002 period. This is 11,289 more than the number of workers who exhausted their regular benefits during February – July 2000. By contrast, the increase in the number of workers exhausting their benefits between February – July 2000 and February – July 2002 was 7,701. Thus, the increase in the number of exhaustees in Alabama between February – July 2000 and February – July 2002 was 47 percent greater than the increase in the number of exhaustees over the comparable two-year period in the previous recession.