Much of the Projected Non-Social Security

Surplus Is a Mirage:

Vast Majority of Surplus Rests on

Assumptions of Deep Cuts

in Domestic Programs that Are Unlikely to Occur

by Sam Elkin and Robert Greenstein

Estimate of

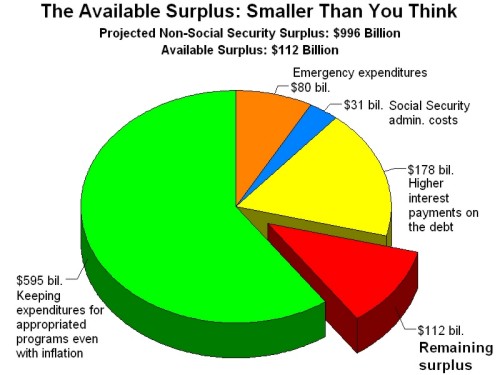

Available Surplus Lower Based on Congressional Budget Office data, this analysis shows that when realistic assumptions are used, the non-Social Security surpluses total only about $112 billion over the next 10 years. Earlier Center versions of this analysis showed modestly larger available surpluses. The revisions in this analysis stem from two factors. First, on July 12, the Congressional Budget Office issued a table that raised CBO's estimate of the portion of the CBO surplus projection that results from the assumption that discretionary spending will be cut. CBO had earlier estimated that $584 billion of the projected surplus was attributable to assuming that non-emergency discretionary spending would be reduced below the FY 1999 level of non-emergency discretionary expenditures, adjusted for inflation. CBO now estimates that $595 billion of the surplus projection is due to this assumption. Second, an earlier Center analysis did not address the assumption in the CBO projections that there would be no emergency expenditures for the next 10 years. This revised Center analysis does address this matter. |

Congressional Budget Office figures released July 1 indicate that the large majority of the budget surplus projected outside Social Security is essentially artificial because it depends on unrealistic assumptions that large, unspecified cuts will be made over the next 10 years in appropriated programs and that there will be no emergency expenditures over this period. When the more realistic assumption is made that total non-emergency expenditures for appropriated programs will neither be cut nor increased and will simply stay even with inflation — and that emergency expenditures will continue at their 1991-1998 average level — nearly 90 percent of the projected non-Social Security surplus disappears.(1)

The new CBO projections show that under current law, the federal government will begin running surpluses in the non-Social Security budget in fiscal year 2000 and run cumulative non-Social Security surpluses of $996 billion over the next 10 years. But these projections, like those OMB issued several days earlier, assume that total expenditures for appropriated programs — which include the vast bulk of defense expenditures — will remain within the austere and politically unrealistic "caps" the 1997 budget law set on appropriated programs.(2)

- To remain within the FY 2000 caps will entail cutting appropriated (i.e., discretionary) programs billions of dollars below the FY 1999 level. No one expects this to occur. Leaders of both parties have acknowledged that a number of appropriations bills cannot pass unless the amount of funding provided for the bills is at significantly higher levels than the current caps allow.

- The caps for FY 2001 and 2002 are more unrealistic than the FY 2000 cap; the caps for those years are significantly lower than the FY 2000 cap when inflation is taken into account. Moreover, the CBO and OMB projections assume that for years after 2002, total expenditures for appropriated programs will remain at the level of the severe cap for FY 2002, adjusted only for inflation in years after FY 2002. This means that the surplus projections assume levels of expenditures for appropriated programs for fiscal years 2001 through 2009 that are lower, when inflation is taken into account, than the highly unrealistic FY 2000 cap that almost certainly will not be met.

- Also of note, both parties have proposed significant increases in defense spending in coming years. Defense spending constitutes about half of overall expenditures for appropriated programs. In addition, legislation enacted last year requires increases in highway spending in coming years. These factors are further reasons why the caps are unlikely to be sustained.

CBO must base its budget projections on current law. The spending caps on appropriated programs are current law. CBO has acted properly in developing its projections. But policymakers who act as though the $1 trillion in non-Social Security surpluses projected over the next 10 years all represent new funds that can go for tax cuts or program expansions appear to misunderstand the meaning of the projections.

- Because the CBO projections rest on the assumption that expenditures for appropriated programs will be held to the levels of the caps, these projections assume that over the next 10 years, these expenditures will be reduced $595 billion below current (i.e., FY 1999) levels of non-emergency discretionary spending, adjusted for inflation. (The $595 billion figure is found in a CBO table on this matter issued July 12.)

Since defense spending is widely expected to rise, all of these $595 billion in cuts would have to come from non-defense programs, primarily domestic programs. This would entail reducing overall expenditures for non-defense appropriated programs by 15 percent to 20 percent over the next 10 years, after adjusting for inflation. Since some areas of non-defense spending such as highways are slated to increase, other areas would need to be cut deeper than 15 percent to 20 percent. Achieving cuts of this magnitude in non-defense appropriated programs would be unprecedented.

- Cutting federal expenditures results in lower levels of debt. CBO projects that the $595 billion in reductions in appropriated programs assumed in its baseline would generate $154 billion in additional savings over the next 10 years through lower interest payments on the debt. Consequently, the reductions in appropriated programs that the CBO projections assume result in total savings of $749 billion over the next 10 years.

| CBO projection of non-Social Security surplus over 10 years | $996 |

| Amount needed to keep non-emergency spending for appropriated programs even with inflation | -595 |

| Likely emergency expenditures (based on average annual emergency expenditures, FY 1991-1998) | -80 |

| Social Security administrative costs (CBO counts as a Social Security expenditure, but Congress counts as a non-Social Security expenditure) | -31 |

| Higher interest payments on debt due to higher levels of spending for appropriated programs than the CBO projections assume | -178 |

| Remaining surplus available for other uses (if some of this is used for tax cuts or program expansions, interest payments will rise further above the CBO projection, requiring some of the $112 billion to be used for interest costs) | 112 |

These $749 billion in assumed savings account for 75 percent — or three-fourths — of the non-Social Security surplus projected over the next 10 years. Since most or all of these cuts are unlikely to materialize, a large majority of the surplus projected in the non-Social Security budget is essentially a mirage.

Emergency Spending

Nor does this represent the full extent to which the CBO projections rest on assumptions that lead to an overstatement of the likely non-Social Security surplus. The CBO projections assume no emergency spending for the next 10 years. There will, of course, be emergencies over the next 10 years that result in government expenditures. There have been emergency expenditures outside the spending caps every year since the Budget Enforcement Act of 1990 established the caps. Hurricanes, tornados, floods, and international emergencies will not magically disappear.

Over the 1990's, emergency funding has averaged $8 billion a year, excluding both emergency expenditures for Desert Storm in the early 1990s and the higher level of emergency spending in fiscal year 1999.(3) The most prudent assumption to make is that emergency expenditures will continue to average about $8 billion a year.

This means an additional $80 billion of the projected surplus over the next 10 years is not likely to materialize since it will be used for emergency expenditures. This $80 billion in expenditures will cause interest payments on the debt to be $24 billion higher than the levels the CBO projections assume.

Congressional and

Clinton Budgetary Treatment of The Congressional budget resolution approved earlier this year assumes a very large tax cut of $778 billion over 10 years. The resolution can accommodate a tax cut of this magnitude because it assumes that none of the surplus will go to placing spending for appropriated programs at a more realistic level. Moreover, the budget resolution assumes that additional cuts in appropriated programs of nearly $200 billion over 10 years will be instituted, on top of the already unrealistic reductions assumed in CBO's projections. (These additional reductions would come in years after 2002.) Under the budget resolution, overall expenditures for non-defense appropriated programs would be cut 29 percent between FY 1999 and FY 2009, after adjusting for inflation. The Clinton budget would add back somewhere in the vicinity of $500 billion over 10 years for appropriated programs, or most of the $595 billion needed to keep non-emergency spending for appropriated programs even with inflation. The Clinton budget only uses $328 billion of the surplus, however, for this purpose. The remaining funds would be raised through a series of offsetting cuts in entitlement programs and tax increases, such as a cigarette tax increase. Many, if not most, of these offsets are given little chance of passage on Capitol Hill. If these offsets are not approved and no funds from the surplus are provided for appropriated programs beyond the $328 billion the Administration has proposed, appropriated programs would have to be cut approximately $270 billion over 10 years below current levels, adjusted for inflation. (To compute the exact amount appropriated programs would have to be reduced under this scenario requires data not yet available on the Administration's new budget plans.) In addition, the Administration's budget does not appear to reserve a portion of the surplus for the emergency expenditures that inevitably will occur. |

Another $31 billion also must be subtracted from the projected non-Social Security surplus; it is needed for the administrative costs of operating Social Security. As the Congressional Budget Office explains on page 6 of its new report, CBO counts these $31 billion in costs as a Social Security expenditure, but Congress treats them as part of the non-Social Security budget and counts them against the spending caps on discretionary programs. (The Congressional budget resolutions passed each year include these expenditures as non-Social Security expenditures that affect the size of the non-Social Security surplus. It is the budget resolution, not the CBO projections, that Congressional budget rules enforce.) Counting these costs as part of the non-Social Security budget reduces the non-Social Security surplus.

When this $135 billion — $80 billion for emergency expenditures, $24 billion for related interest payments on the debt, and $31 billion for Social Security administrative costs — is added to the $749 billion described above in expenditures for appropriated programs and related interest payments on the debt, a total of $884 billion — 89 percent of the projected non-Social Security surplus — dries up. Only $112 billion remains. (See table on page 3.) In addition, non-Social Security surpluses of any size do not appear until 2006; the non-Social Security budget either continues to show deficits or is in balance (but without significant surpluses) until that time.

One other caution regarding the surplus projections should be noted. The economic and technical assumptions underlying the forecast could prove too rosy (or not rosy enough). CBO has repeatedly warned that a high degree of uncertainty attaches to budget projections made several years in advance. In a report issued earlier this year, CBO noted that if its projections for fiscal year 2004 prove to miss the mark by the average percentage amount that CBO projections made five years in advance have proved to be off over the past decade, its surplus forecast for 2004 will be off by $250 billion.(4) If economic growth is modestly slower than forecast or health care costs rise substantially faster than is currently projected, budget surpluses could be substantially lower than those reflected in the CBO estimates.

Trends in Discretionary Spending Expenditures for appropriated (i.e., discretionary) programs are already low in historical terms as a percentage of GDP. There is serious question about how much further they can be expected to decline.

Discretionary spending may be approaching its limits in terms of how much more it can fall as a share of GDP. That may be one of the lessons both of last year's highway bill and of last October's omnibus appropriations bill, which exceeded the budget limits for discretionary spending and designated the overage as emergency spending. While non-defense discretionary spending has fallen over the past several decades as a share of GDP, it has not declined in inflation-adjusted terms (although it has declined since 1980 if an adjustment reflecting the increase in the size of the U.S. population is made as well). If we have emerged from a period of deficits without expenditures for non-defense discretionary programs having declined in inflation-adjusted terms, there is little reason to believe the political system will exact deep cuts in this part of the budget when the outlook is sunny, surpluses have emerged, and pent-up demands for various types of discretionary spending are coming to the fore (witness the aviation bill the House recently approved). This underscores the unrealistic nature of the assumptions of substantial reductions in discretionary program expenditures that underlie the projections of $1 trillion non-Social Security surpluses. |

How Much of the Surplus is

Available for Tax Cuts,

Medicare, and Social Security if More Realistic Assumptions Are Used?

In summary, if more realistic assumptions are used — namely, that total non-emergency expenditures for discretionary programs will remain at the fiscal year 1999 level, adjusted for inflation, and emergency spending will remain at its average level for the recent past — a very different picture emerges of how much in surplus funds is available for tax cuts, shoring up Medicare and Social Security, and other initiatives. Under this more plausible scenario, only about $112 billion remains available, and hardly any of it is available in the next five years.(6)

It may be noted that to assume, as we do here, that total non-emergency expenditures for appropriated programs will be no higher in future years than non-emergency expenditures for such programs in fiscal year 1999, adjusted for inflation, is to use a conservative assumption. It is a foregone conclusion that defense spending will rise faster than inflation. Hence, for overall non-emergency expenditures for appropriated programs to remain even with inflation, non-defense programs must be cut in real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) dollars. Yet spending for some non-defense program areas such as highways is already slated to rise. The House recently passed legislation to boost aviation spending as well. Thus, the assumption used here for expenditures for appropriated programs may be too low.

These findings have major implications for policymakers. For there to be sufficient surplus funds to finance the large tax cuts some policymakers advocate, Congress would have to make cuts of unprecedented depth in appropriated programs over the next 10 years — cuts substantially deeper than those policymakers are balking at passing this year.

End Notes:

1. We use the average level of emergency spending in fiscal years 1991 through 1998, other than expenditures for Desert Storm. This also excludes the high level of emergency spending in fiscal year 1999. The term "appropriated programs," as used here, means discretionary programs.

2. Technically, OMB assumes expenditures for discretionary programs that exceed the caps, but it also assumes offsetting reductions in mandatory programs and tax increases.

3. The $8 billion figure represents average funding for emergencies other than Desert Storm for fiscal years 1991 through 1998, as expressed in 1999 dollars.

4. In computing the average percentage amount by which CBO projections made five years in advance have proven to be off, CBO excluded the effects of legislation on deficits or surpluses. The $250 billion figure is based on the average percentage amount by which the budget projections missed the mark due solely to economic and technical factors. See CBO, The Economic and Budget Outlook: Fiscal Years 2000-2009, January 1999, p. xxiii.

5. This level also stood at 3.4 percent of GDP in 1962 and 1989. There is no year since 1962 when it was lower than 3.4 percent of GDP.

6. There would be a small non-Social Security surplus in fiscal year 2002.