|

Revised October 11, 2007

THE HIGH COST OF ESTATE TAX REPEAL

By Joel Friedman

Making permanent the repeal of the estate tax after 2010 — as proposed by the President — would add more than $1.1 trillion to the deficit between fiscal years 2012 and 2021, the first ten years in which the full costs of extending repeal would be reflected in the budget. This cost includes $859 billion of lost revenues and $251 billion of higher interest payments on the national debt. Each year of repeal would cost slightly more, in today’s terms, than everything the federal government now spends on homeland security, and considerably more than it now spends on education.

The revenue-loss projection is based on official Joint Committee on Taxation estimates of the cost of repeal, which show lost revenues of $499 billion between 2008 and 2017, including a $91 billion revenue loss in 2017 alone. (The Treasury Department estimate is similar: a $442 billion ten-year cost for repeal.) These estimates understate the full fiscal impact of estate tax repeal, however, because the ten-year period covered by the official estimates includes only six years in which the costs of making repeal permanent would be fully felt (see Figure 1).[1]

To develop a ten-year cost estimate that reflects the cost of ten years of repeal requires producing an estimate that extends for an additional four years, through 2021. This can readily be done by using the Joint Tax Committee estimate of the cost of repeal through 2017 and simply assuming that the revenue loss from estate tax repeal remains constant, as a share of the economy, in years after 2017.[2]

Some have tried to argue that the $1.1 trillion cost estimate is implausible since the estate tax raised only $22 billion in revenue in 2005, according to the most recent IRS data. The amount of estate tax revenue collected in 2005, however, is not a good indicator of the long-term budgetary impact of estate-tax repeal, for three basic reasons.

-

First, the Joint Tax Committee finds that repealing the estate tax will reduce not only estate tax revenue but also income and gift tax revenue. In particular, the Joint Tax Committee expects repeal of the estate tax to reduce capital gains revenue by increasing the “lock-in effect,” whereby people choose to hold appreciated assets until they die rather than to sell the assets while they are alive and pay the capital gains tax.

-

Second, unlike the IRS figure, the $1.1 trillion cost includes the additional interest payments on the national debt that will have to be paid as a result of repeal, because the cost of repeal would be financed through higher debt rather than through offsetting budget cuts or tax increases. This estimate of the interest costs uses the Congressional Budget Office’s standard methodology for estimating the increase in interest payments that results from tax cuts and spending increases that are not paid for.

-

Finally, the $1.1 trillion estimate covers the 2012-2021 period, because that is the first decade in which the full cost of repeal is captured in all ten years. This period includes years in which the economy is projected to be larger and the country wealthier, and prices higher, than today. A comparable estimate for the 2008-2017 period likely would be about one-sixth lower.

It also should be noted that the official cost estimates of a tax or spending proposal measure the cost of such a proposal relative to current law. Estimates of the cost of estate tax repeal consequently compare its costs to what would transpire under the current law, under which the estate tax is slated to be reinstated in 2011 with a $1 million exemption ($2 million a couple) and a 55 percent tax rate. Most changes in the estate tax that have been proposed would have significant costs relative to current law. For instance, making permanent the estate tax as it will exist in 2009 — with a $3.5 million exemption ($7 million per couple) and a 45 percent rate — would cost about $500 billion over the 2012-2021 period, or about 45 percent of the cost of repeal.

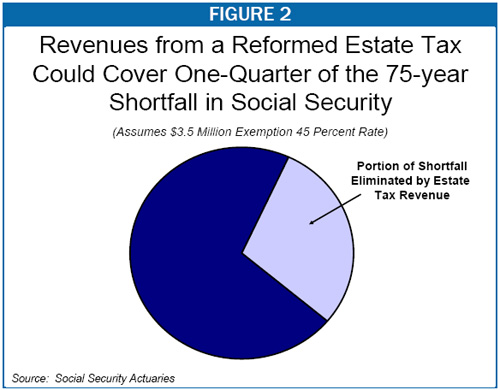

Social Security Actuaries Project Significant Estate Tax Revenue Over the Long Run

Despite the significant cost associated with reforming the estate tax by freezing it at the 2009 levels, however, such a reform still would bring in considerable revenue. For instance, the actuaries at the Social Security Administration have examined the long-term impact of a proposal by Robert Ball, who served as Social Security Commissioner under Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon. Ball would maintain the estate tax at its 2009 level and dedicate the revenues to Social Security. The actuaries estimate that such an estate tax would raise enough revenue to close more than one-quarter of the Social Security shortfall over the next 75 years (see Figure 2).[3] An estate tax with a lower exemption level or higher tax rate than would be in place in 2009 would close an even larger share of the Social Security shortfall.

|

Repealing the Estate Tax Would Not Raise Revenue, Contrary to Claims by the Wall Street Journal

In a misleading editorial, the Wall Street Journal implied that repeal of the estate tax would actually raise revenue. The premise of the editorial’s argument was that the Joint Committee on Taxation's estimate of the cost of repeal somehow ignores the impact of another provision attached to repeal of the estate tax. That provision would repeal what is known as “step-up basis,” a system that exempts heirs from paying capital gains tax on the increase in the value of an asset (such as stocks, bonds, artwork, and real estate) that occurred prior to the asset being inherited. But as the Wall Street Journal acknowledges part way through the editorial, the Joint Tax Committee has stated quite clearly that its estimates do take into account the change in the step-up basis rules. The real issue is that the Joint Tax Committee (and the Treasury Department) does not believe that eliminating step-up basis will raise much revenue, contrary to the unsupported claims of the Wall Street Journal editorial page.

That the Joint Tax Committee reaches this conclusion is not surprising. First, under the estate tax rules that surround repeal of the tax, step-up in basis will continue to be the law of the land for virtually all estates. Under repeal, step-up basis is partially replaced with a new rule known as “carryover basis,” whereby heirs (when they sell an inherited asset) are responsible for paying capital gains tax on the increase in the asset's value dating back to when it was first purchased by the decedent. The new rules provide a huge exemption, however, so that married couples can pass on assets that have appreciated by $4.3 million with these assets still being subject to the old step-up basis rules. (Without this exemption, millions of families who would not have paid the estate tax would suddenly find themselves subject to higher capital gains taxes after the estate tax is repealed.)

Second, for those heirs inheriting substantial assets — beyond the $4.3 million exemption — there is no reason to think they would rush out and sell these assets to generate the capital gains revenue claimed by the Wall Street Journal editorial writers. In some cases, these assets represent businesses and farms the heirs will continue to operate. Further, a major asset in most estates — the residence of the decedent — is largely exempt from capital gains tax already, because current law provides a $500,000 exemption for couples on the sale of their homes.

Finally, the Joint Tax Committee and Treasury estimates may understate the likely cost of estate tax repeal, because few believe that carryover-basis rules can actually be sustained or even implemented in the real world. Requiring heirs to keep track of the original purchase price of assets across multiple generations is viewed by most tax experts as administratively unworkable. Carryover basis was enacted before but never implemented for this reason: in the 1970s, it was enacted but rescinded before it could take effect, because the IRS concluded it could not be effectively administered. Step-up basis offers a practical solution to the problem of measuring the appreciation of assets over long periods of time, by essentially allowing heirs to restart the clock. In the end, even the few revenues that carryover basis could theoretically raise would not materialize if, as is likely, the carry-over basis rules were again abandoned as unworkable. |

The estimates by the Social Security actuaries of the impact of a reformed estate tax on the Social Security shortfall are an indication of the substantial revenues that an appropriately reformed estate tax can produce. Dedicating estate tax revenue to Social Security is, of course, just one example of how such revenue could serve important goals. The revenue also could be used to reduce the deficit or to address other critical national needs. In contrast, eliminating the estate tax not only would mean that large amounts of revenue would be lost, but also that tens of millions of other U.S. taxpayers — nearly all of whom are less wealthy than the households who would benefit handsomely from estate-tax repeal — ultimately would have to foot the bill, by being subject to reductions in other government benefits and services on to which they rely or to increases in other taxes, or by bearing the burden of a significantly higher national debt.

End Notes:

[1] Since there normally is a lag of about a year between an individual’s death and the payment of any tax owed on that individual’s estate, the cost of extending estate-tax repeal so that it remains in effect in 2011 and succeeding years will not be felt in full until fiscal 2012. Thus, only six full years of the measure’s cost show up in estimates that cover the ten-year period from fiscal 2008-2017.

[2] Assuming that the cost of a tax cut remains constant in future decades, when measured as a share of the economy, is a common approach that the Congressional Budget Office, the Government Accountability Office, and other institutions use in making long-term budget projections. Moreover, this estimate would most likely understate the long-term cost of estate tax repeal, in large part because the exemption level under current law is not indexed for inflation.

[3] Stephen C. Goss, "Memorandum to Robert M. Ball: Estimated OASDI Financial Effects for a Proposal With Six Provisions That Would Improve Social Security Financing," Social Security Chief Actuary, April 14, 2005. |