|

Revised August 9, 2006

GREGG BILL WOULD MAKE FAR-REACHING CHANGES IN BUDGET RULES

Bill Would Aim Budget Knife at Domestic Programs

While Shielding Tax Cuts from Fiscal Discipline

by Robert Greenstein, James Horney, and Richard Kogan

Sweeping legislation to radically alter federal budget procedures, designed by Senate Budget Committee chairman Judd Gregg and endorsed by Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist, was adopted by the Budget Committee on June 20. The bill may be brought to the Senate floor this summer (either as a single piece of legislation or as several separate bills). The legislation seeks to force dramatic changes in the budget. If enacted, it could have profound effects on American society.

In unveiling the bill earlier in June, Senator Gregg described it in moderate terms as offering “common-sense and fiscally responsible solutions” to problems like “duplicative and wasteful spending.” The legislation fails, however, to include common-sense budget reforms that have proved effective in the past, such as restoration of the Pay-As-You-Go rules on entitlement increases and tax cuts. Instead, the bill contains radical measures that could lead to massive cuts over time in Medicaid and Medicare and reductions in the vast majority of domestic programs, while shielding tax cuts from any fiscal discipline. The bill would do the following:

-

Impose caps on funding for discretionary programs that would force substantial cuts in public services. The Gregg bill would lock in, for the next three years, the overall discretionary funding levels proposed in President Bush’s most recent budget. To hit those levels, the President’s budget proposes $66 billion in domestic discretionary cuts over the next three years. By 2009, the President’s cuts would hit every domestic discretionary program area in the budget, with the sole exception of space, science, and technology.

-

Set fixed deficit targets, falling to 0.5 percent of GDP by 2012, enforced by automatic across-the-board cuts in all entitlement programs except Social Security. CBO’s budget projections indicate that if the President’s tax cuts (except for estate-tax repeal) are made permanent,[1] relief from the Alternate Minimum Tax is continued, the President’s defense build-up is funded, and operations in Iraq and Afghanistan phase out over the next several years, the deficit will equal 1.9 percent of GDP in 2012. The gap between this projected deficit and the 0.5 percent of GDP deficit target in the Gregg bill would amount to $244 billion in 2012. If Congress did not enact legislation to close this gap, this entire $244 billion in savings would have to be achieved through across-the-board cuts in entitlement programs, including basic assistance programs for the poor and the unemployed, veterans programs, and Medicare. (The discretionary caps, if adhered to, would close some of this gap; new tax cuts, on the other hand, would widen it.)

-

Establish new definitions of “solvency” for Medicare and Medicaid that are unrelated to how these programs are financed, have a marked ideological tilt, and could not be met without harsh changes. The legislation would define Medicaid “solvency” in a way that likely could be achieved only by abolishing Medicaid in its current form and replacing it with a block grant to states under which federal funding would grow much more slowly than health care costs, and with no allowance being made for the increased Medicaid costs that will result from the aging of the population. To meet this “solvency” target, federal Medicaid funding would have to be cut a stunning 22 percent by 2020, 36 percent by 2030, and 50 percent by 2042 (relative to CBO’s baseline projections).

Similarly, meeting the Gregg bill’s Medicare “solvency” target would require massive increases over time in the premiums, deductibles, and co-payments that elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries pay, sharp restrictions on the health care services that Medicare covers, or cuts in payments to health care providers that could exceed 30 percent by 2030.

-

Establish a “fast-track” legislative mechanism that could allow a narrow partisan majority to ram through Congress terminations of (and major changes in) discretionary and entitlement programs. The bill would establish a commission to propose legislation calling for program terminations and realignments (such as consolidations of programs into block grants at reduced funding levels). The bill would allow a bare partisan majority on the commission to approve the plan, and allow the plan then to be pushed through Congress under fast-track procedures without any minority-party votes needed — and with no amendments allowed either in committee or on the House and Senate floors. With their votes irrelevant and their amendments disallowed, members of the minority party could effectively be disenfranchised.

Shielding Tax Cuts from Fiscal Discipline

While establishing procedures that could trigger cuts in everything from education to school lunches and benefits for disabled veterans, the Gregg bill would shield tax cuts from fiscal discipline. The Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center estimates that the tax cuts enacted in 2001 and 2003 are now worth an average of $112,000 a year to households with annual incomes of over $1 million and that the average tax cut for these households will reach more than $130,000 (in today’s dollars) by 2012 if the tax cuts are extended. Data from the Tax Policy Center and the Joint Committee on Taxation also indicate that the cumulative cost of the tax cuts just for the top 1 percent of the Americans (those with incomes over about $400,000 in 2006) will approach $1 trillion over the coming decade. Moreover, CBO data indicate that the tax cuts enacted since 2001 have been responsible for as much of the increase in the deficit over the 2002-2011 period as all domestic, defense, and international spending increases combined since 2001, including the spending on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The Gregg bill would protect the tax cuts. It would, if Congress continues to fully fund the President’s military requests, place virtually all of the burden of addressing the nation’s fiscal problems on domestic programs, including programs upon which tens of millions of Americans of modest means rely.

Cuts in Domestic Discretionary Programs

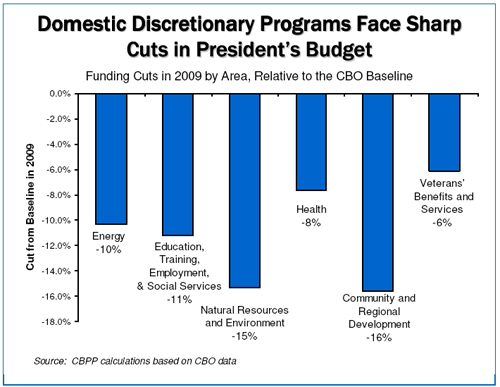

As noted, the Gregg bill would cap overall discretionary funding levels for the next three years at the levels proposed in the President’s budget. That budget proposes $66 billion in cuts in domestic discretionary programs over the next three years, with the cuts growing deeper each year. The cuts proposed by the President would touch almost all categories of domestic programs, with even high-priority areas slated for substantial cuts (see chart below).

For example, under the President’s budget, the acclaimed women, infants, and children nutrition program (WIC), which the Bush White House has singled out for praise as one of the most effective federal programs, would be cut $459 million in 2009. That would entail reducing the number of low-income pregnant women, infants, and young children at nutritional risk whom the program serves by an estimated 680,000.[2] Similarly, the Bush budget would cut vocational and adult education by 73.5 percent ($1.5 billion) in 2009. The Environmental Protection Agency’s clean water programs would be cut 19 percent ($354 million). The low-income home energy assistance program would be cut 49 percent ($1.6 billion). Even the National Institutes of Health would be cut 8 percent ($2.5 billion). (These reductions are measured relative to the Congressional Budget Office baseline, which equals the 2006 funding levels, adjusted for inflation.)

Deficit Target Mechanism Puts Poor Families, Veterans, and Others at Risk

The Gregg proposal would set fixed deficit targets that would decline from 2.75 percent of the Gross Domestic Product in 2007 to 0.5 percent of GDP in 2012 and every year thereafter. If these deficit targets would otherwise be missed, across-the-board entitlement cuts would automatically be triggered, with the cuts being set at whatever percentage reduction was needed to hit the target.

As noted, if the President’s tax cuts (except for full estate tax repeal) are made permanent, relief from the AMT is continued, and the President’s defense build-up is funded, the deficit will equal 1.9 percent of GDP in 2012 even if operations in Iraq and Afghanistan have been phased out by then. The gap between this projected deficit and the Gregg bill’s target (0.5 percent of GDP) would amount to $244 billion in 2012, meaning that $244 billion in deficit reduction would be required. The gap between projected deficits and the deficit target would grow larger in years after 2012, requiring even larger amounts of deficit reduction in those years.

The cuts in discretionary programs that would be needed to comply with the bill’s discretionary caps would close only about one-eighteenth of this gap. Over the ten years from 2007-2016, Congress also would have to cut entitlement programs by a cumulative total of $1.6 trillion to hit the deficit targets, unless it were willing to close part of the gap by raising revenues and/or cutting discretionary programs below the cap levels.[3]

If Congress failed to cut enough to hit a given year’s target, all of the savings needed to hit the target would be obtained through automatic, across-the-board cuts in every entitlement program except Social Security. Table 1 shows the magnitude of the cuts that would be made in various entitlement programs if the $1.6 trillion in entitlement reductions were secured through the automatic cuts (i.e., if all entitlements except Social Security were cut by the same percentage).

This component of the Gregg bill is modeled on the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings (GRH) legislation enacted in 1985 and revised in 1987 (which proved largely unsuccessful in reducing deficits for reasons discussed in the body of this analysis). But the Gregg bill departs from the GRH law in several fundamental respects. All of the departures make the Gregg approach less equitable — and more ideological — than the old GRH law.

|

TABLE 1 |

|

Cuts in Various Entitlement Programs, 2007-2016 |

|

(in billions of dollars) |

| Medicare |

693 |

| Medicaid/SCHIP |

366 |

| Federal civilian retirement |

102 |

| EITC/Child Tax Credit |

60 |

| Military retirement |

60 |

| SSI |

56 |

| Unemployment insurance |

56 |

| Veterans benefits |

50 |

| Food stamps |

45 |

| TANF, CSE, and related |

24 |

| Farm programs |

20 |

| School lunch/child nutrition |

20 |

| TRICARE |

14 |

| Foster care/adoption assistance |

10 |

| Student loans |

4 |

-

Under the old GRH law, if automatic cuts were triggered, half of the cuts had to come from defense programs and half from domestic. (The domestic cuts would be made in both discretionary and entitlement programs.) This aspect of the old GRH law was purposefully designed to be painful to policymakers from across the political spectrum, so everyone would have an incentive to try to reach agreement on bipartisan deficit-reduction measures that could avert the automatic cuts. By contrast, the Gregg bill shields defense from the automatic cuts, by limiting the automatic cuts to entitlement programs. It thereby requires that virtually all of the automatic cuts come from non-defense programs. Rather than inflicting pain on policymakers and interest groups from across the political spectrum, in hopes of bringing all of them to the negotiating table, the bill’s automatic cuts would inflict pain on one part of the budget — domestic programs.

-

In addition, under the old GRH law, basic programs for the poor — such as the Supplemental Security Income program for the elderly and disabled poor, free school lunches for poor children, food stamps, and the Earned Income Tax Credit for the working poor — were exempt from the automatic cuts. So were veterans disability compensation and veterans pensions. All budget-process laws enacted since 1985 that have contained automatic cuts have exempted these programs from those cuts. Not the Gregg bill, however. It abandons these protections. Programs for the poor and even for disabled veterans would be hit with full force when the automatic-cut axe fell.

The Gregg bill’s fixed deficit targets also represent unsound economic policy. Deficits increase when the economy slows. As a consequence, the budget cuts needed to meet the fixed deficit targets that the bill sets would be largest in the years when the economy was weakest. Economists widely regard this as an ill-advised course that stands basic economics on its head and risks tipping a faltering economy into recession.

Line-item Veto

The Gregg bill also would give the President line-item veto authority. Most budget experts are skeptical that such authority will do much to reduce deficits and believe it is likely to have more of an effect in enhancing the President’s leverage over Congress on a range of matters than in strengthening fiscal discipline.[4]

The line-item-veto provision in the Gregg bill is particularly troubling in this respect. It would give the President one year after enactment of a bill to propose the cancellation of provisions in it. It would then allow the President to withhold the funds proposed for cancellation for 45 days after submitting his veto request, regardless of Congressional action. This would enable a White House to use these procedures to withhold some appropriated funds through the end of a fiscal year, which could cause the funds to lapse — and the appropriation thereby to be cancelled — even if Congress had voted to disapprove the veto.

Moreover, the President would be allowed to package cancellation of items from different bills into a single veto package, and Congress would have to vote to accept or reject the package as a whole, with no amendments allowed. The President could combine vetoes of egregious earmarks that had received damning publicity with vetoes of more meritorious items from other bills that he opposed on ideological grounds — and confront Congress with an “all or nothing” vote. This could lead to the cancellation of some programs that, by themselves, enjoyed support from a majority of Congress. It should be noted that the line-item veto’s likely use would extend far beyond earmarks; it could be used to eliminate entire programs.

Failure to Include Key Reforms

Finally, the Gregg legislation is as notable for what it excludes as for what it includes. It fails to include the single reform that budget watchdog groups, the Government Accountability Office, and former Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan all have said is critical to restoring fiscal discipline — the restoration of Pay-As-You-Go rules on both entitlement increases and tax cuts. A recent analysis that have conducted, based on CBO’s long-term budget projections through 2050, indicates that enacting — and abiding by — PAYGO rules could close as much as two-thirds of the “fiscal imbalance” through 2050.

The Gregg proposal also fails to include another reform that budget watchdog groups have stressed — restoring the original intent of the fast-track budget reconciliation process by barring its use to facilitate passage of legislation that increases deficits. Although the Gregg bill requires that entitlement increases be paid for, it allows deficit-financed tax cuts to continue being enacted without limit and also allows the continued abuse of the reconciliation process to push through large deficit-financed tax cuts.

In addition, unlike the bipartisan 1990 deficit-reduction legislation, which contained $500 billion over five years in specific program cuts and tax increases (mostly on high-income households) — and also established the PAYGO rules — the Gregg bill contains no specific policy changes. In fact, if the Gregg bill were enacted, that likely would make it more difficult to achieve a large-scale, bipartisan deficit-reduction agreement. To achieve such an agreement, policymakers from across the political spectrum must fear the consequences of failing to act and must be willing to give some ground on their own policy priorities in return for other policymakers with different priorities giving ground on theirs. Under the Gregg bill, however, policymakers on the right would likely see little reason to come to the bargaining table. Why negotiate a bipartisan agreement that likely would increase revenues, as well as cut spending, when you can do nothing and let the Gregg bill’s caps and automatic cuts place most of the burdens on domestic programs, while sparing tax cuts entirely?

The bill does include some provisions that should prove beneficial in improving budget debates, such as a provision to ensure that cost estimates are available on conference reports before those reports are voted on. Such provisions are, however, a minor part of the bill.

In short, the Gregg bill fails either to make any specific hard choices or to call for even a modicum of shared sacrifice. It is assiduous in its protection of deficit-financed tax cuts, even as it seeks to establish procedures to put domestic programs under the knife. It seeks to cloak itself in rhetoric about fiscal responsibility, but its dedication to protecting costly tax cuts from fiscal discipline makes its proclaimed commitment to fiscal responsibility ring hollow.

|

Former Congressman and Actor Likens Budget-Process Bills to Hollywood Stunt

The propensity of Members of Congress to turn to budget process changes to give the appearance of action to reduce the deficit while carefully avoiding the painful actions that really would do something about the deficit — cutting specific programs and raising specific taxes —was colorfully, and accurately, described by former Congressman Fred Grandy. Grandy, who starred in the popular TV show “The Love Boat” before being elected as a Republican member of the House from Iowa, explained how Congressional consideration of budget process changes (akin to those included in the Gregg legislation) reminded him of a Hollywood technique used to convey a false impression:

“Back in my Love Boat days, whenever we wanted to simulate the ship at sea, we would set up a guard rail, project the ocean behind it, and the world would think we were cruising at sunset instead of hunkered down in a sound stage on Sunset Boulevard. That's called a process shot in Hollywood. In Washington, the legislative equivalent of the process shot is a balanced budget amendment, term limit provision, or any artifice that creates the illusion of movement while the men and women of government continue to stand still when it comes to making tough choices.”[1]

1 Fred Grandy, National Public Radio’s All Things Considered, April 6, 1995. |

Specific provisions of the legislation include the following.

1. The return of Gramm-Rudman-Hollings-style fixed deficit targets.

The Gramm-Rudman-Hollings (GRH) law enacted in 1985 established fixed deficit targets that were to decline each year until the budget was balanced in 1991. If the projected deficit for a given year would exceed the deficit target for that year, automatic across-the-board cuts would be instituted in both entitlement and discretionary programs, with basic programs for the poor, veterans disability compensation, unemployment insurance, and a few other programs exempt from the across-the-board cuts (and with automatic cuts in Medicare, veterans’ health care, and some other programs limited to 2 percent).

The GRH law proved to be a failure. Deficits are naturally much higher in years when the economy is weak than in years when it is strong. Because the GRH law set fixed dollar targets that were not adjusted upward when the economy slowed, it required deeper cuts when the economy weakened, even though that is precisely the time when such cuts can be dangerous to the economy.

Under GRH, when Congress and the President were faced with the need for deep cuts to hit the deficit targets (either through legislation or through the automatic cuts), they invariably ducked. They consistently adopted “rosy scenario” budget estimates that vastly understated deficits (and made the President and Congress something of a laughingstock). They engaged in budget chicanery on an unprecedented scale (and on a bipartisan basis) to make it look, on paper, as though the deficit targets would be hit when everyone knew that was a fabrication. They also passed new legislation within two years of the enactment of the original GRH law to raise the deficit targets so the targets would not be as hard to reach, and then they still missed the targets by large margins. At the end of five years of the GRH law in 1990, the deficit exceeded the original target for that year by a whopping $185 billion.

It was because of the failure of the GRH law that Congress on a bipartisan basis wisely replaced it in 1990 with the Budget Enforcement Act. In 1990, Congress made a series of tough choices in specific policies and programs — reducing entitlement programs, raising taxes, and limiting discretionary spending — that shrank the deficit by almost $500 billion over five years. Congress accompanied these specific policy changes with new budget rules, the central feature of which was the requirement that all entitlement increases and tax cuts be fully paid for (i.e., the Pay-As-You-Go rule). The 1990 law and the PAYGO rule were a major success; they played a significant role in the move from deficits to surpluses in the 1990s.

|

Budget Experts Comment on the Failure of the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Law

"The GRH triggers were tied to deficit results and generally regarded as a failure — they were evaded or, when deficit continued to exceed the targets, the targets were changed."

-- Statement of Susan J. Irving, Director of Federal Budget Analysis, Government Accountability Office for a hearing on "Considerations for Updating the Budget Enforcement Act" held by the House Budget Committee on July 19, 2001.

"GRH set fixed deficit targets, with a balanced budget required by five years, and created a "sequestration" enforcement procedure that would be automatically triggered if these targets were breached. Sequestration was dubbed by Senator Rudman as 'a bad idea whose time has come.' In fact, the entire law was flawed and should never have been adopted. Its fixed targets quickly became too ambitious as a weaker-than-expected economy and lack of budgetary control created larger baseline deficits. Sequestration was an empty threat: it would cut mostly discretionary spending when mandatory spending wasn't controlled by reconciliation, and the Congress could stop sequestration simply by changing the law. Deficit targets applied not to actual deficits, but to the projected deficits in the President's budget and the budget resolution. This inspired much gimmickry: the 'rosy scenario' of the early 1980s was replicated in the latter 1980s, just with bigger and scarier numbers."

-- Roy T. Meyers, Professor of Political Science at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and Philip Joyce, Professor of Public Policy and Public Administration, George Washington University, "Congressional Budgeting at Age 30: Is it Worth Saving?," Public Budgeting and Finance, December 2005. |

The Gregg bill, however, ignores this history and charts a different course. It contains no specific reductions in programs or increases in revenues. It does not call for bipartisan negotiations among the President and Congressional leaders, such as occurred in 1990, to hammer out specific program and tax changes. It also fails to reinstate the PAYGO rule, the major budget-process reform that worked.

Instead, it reinstates the failed Gramm-Rudman-Hollings approach, with some changes. Unfortunately, the principal changes would make the Gregg version even more problematic than the original GRH law.

-

The original GRH law set its deficit targets in dollar terms. As noted above, this represents unsound policy because it is “pro-cyclical” — that is, it amplifies the swings in the business cycle and puts the brakes on the economy at the very time when the economy is already weakening, thereby risking pushing a faltering economy into recession. The Gregg bill contains a modification of the GRH law here — it would set its fixed deficit targets as a percentage of the Gross Domestic Product rather than in dollar terms. The targets would start at 2.75 percent of GDP in 2007 and decline to 0.5 percent of GDP in 2012 and every year thereafter.

This modification makes the new Gregg approach even more ill-advised than the original GRH approach. When the economy is weak, the Gross Domestic Product grows more slowly or declines. Thus, under the Gregg bill, when the economy faltered and deficits climbed, the dollar amount of the deficit targets would fall to even lower levels, since GDP would be smaller than had been expected. As a consequence, even larger budget cuts would be required when the economy weakened than would be the case if the deficit targets had again been set in dollar terms.[5]

-

Under the original GRH law, the automatic across-the-board cut mechanism was designed so that when the automatic cuts were triggered, half of the cuts would come from defense programs and half from domestic programs. (Both entitlement and discretionary programs were subject to the GRH automatic cuts.) This was designed to make the automatic cuts painful to President Reagan and to all Member of Congress regardless of party or ideology, in order to increase the chances that all would work together to pass deficit-reduction measures that obviated the need for the automatic cuts. By contrast, the Gregg bill protects defense by focusing the automatic cuts solely on entitlements, so that nearly all of the automatic cuts would come in domestic programs. Among other things, the Gregg mechanism would give hard-line conservatives little incentive to work on a bipartisan basis to fashion compromise legislation to reduce deficits, since tax cuts and defense spending would both be protected from the automatic cuts that would be triggered if deficit targets were missed.

-

In addition, the original GRH law exempted basic programs for the poor — such as Supplemental Security Income benefits for the elderly and disabled poor (a program in which the benefit levels already are well below the poverty line), free school lunches for poor children, the Earned Income Tax Credit for working-poor families, food stamps, and Medicaid — from the automatic across-the-board cuts implemented when deficit targets are missed. The Gregg bill eliminates these exemptions and fully subjects all of these programs — and the poor or vulnerable people they serve — to the across-the-board cuts. The likely result would be increases in poverty and hardship.

These are not small matters. The automatic across-the-board cuts triggered under the Gregg mechanism could be very large. CBO analyses indicate that if the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts are extended,[6] AMT relief is continued, the President’s defense request is funded, and operations in Iraq and Afghanistan phase out over the next several years, the projected deficit for fiscal year 2012 will equal 1.9 percent of GDP. This would be $244 billion above the Gregg target of 0.5 percent of GDP. Some $244 billion of deficit reduction for a single year would be required to avert the automatic cuts.

The cuts in discretionary programs required to meet the bill’s discretionary caps would close only about one-eighteenth of the gap. To hit the deficit targets, a cumulative total of $1.6 trillion in entitlement cuts (on top of the discretionary program cuts) would be required over the next ten years (2007-2016), unless Congress and the President agreed to raise revenues or to cut discretionary programs below the austere caps the bill would set. If Congress did not produce this $1.6 trillion of savings on its own, the automatic-cut axe would fall. Table 1 on page 4 shows the dimension of the reductions in various programs that would be made under the automatic cuts to achieve the $1.6 trillion (i.e., the dimensions of cuts that would be made if all entitlement programs except Social Security were reduced by the same percentage, as would be done under the automatic cuts).

Moreover, the dimensions of the required budget cuts would be still greater if the economy grew more slowly than forecast. The cuts also would have to be even deeper if the nation suffered a national disaster such as a major hurricane or earthquake, since disaster relief would count in the deficit calculations. Disaster relief would force even deeper automatic cuts in all entitlement programs except Social Security. Wars would have this effect, as well.

Finally, additional tax cuts for the well-off also would trigger deeper cuts in entitlement programs. Unpaid-for tax cuts would push deficits further above the Gregg bill’s deficit targets, which in turn would require deeper budget cuts to hit those targets.

2. Requirements for large cuts in discretionary programs.

The Gregg bill would establish statutory caps on total funding (i.e., appropriations) for discretionary programs for each of the next three fiscal years. The caps would be set at the levels proposed in the budget that President Bush submitted in February. If appropriation levels for discretionary programs would exceed these caps in any of the next three years, automatic across-the-board cuts in discretionary programs would be triggered.

To live within the overall level of appropriations that the President has proposed (and the Gregg bill adopts), the Bush budget includes substantial and widespread cuts in domestic programs. The caps in the Gregg bill are intended to lock in overall discretionary cuts of this magnitude. Under the Gregg bill, overall cuts in domestic discretionary programs equal to those in the Bush budget would have to be made, unless Congress funds defense and international affairs at levels below those the President has requested.

-

The CBO analysis of the President’s budget issued earlier this year shows that the budget includes cuts in funding for domestic discretionary programs totaling $66 billion over the next three years, with the cuts reaching $31 billion (or 7.5 percent) in 2009. (Note: These cuts are measured from the CBO baseline, which equals the 2006 funding levels for discretionary programs, adjusted for inflation.)

-

Under the federal budget, domestic discretionary programs are divided into 15 program areas (or “budget functions”). By 2009, the Bush budget would cut every domestic discretionary program area with the sole exception of the science, space, and technology area. Programs in areas ranging from education to medical research, veterans health care, and environmental protection all are slated for hefty cuts by 2009 under the President’s budget. Table 2 shows the depth of the cuts that the President’s budget proposes for 2009 in selected domestic discretionary programs.

|

TABLE 2 |

|

Cuts in Fiscal Year 2009 Funding for Selected Domestic Discretionary Programs

Proposed by President Bush in His Fiscal Year 2007 Budget |

|

Program |

Cut

(in millions of dollars) |

Cut

(as a percent) |

|

|

|

|

|

Women, infants, and children nutrition (WIC)

|

-$459 |

-8.4% |

|

Vocational and adult education

|

-$1,544 |

-73.5% |

|

Children and families services (including Head Start)

|

-$1,401 |

-15.0% |

|

National Institutes of Health

|

-$2,504 |

-8.3% |

|

Low-Income Home Energy Assistance (LIHEAP)

|

-$1,622 |

-48.6% |

|

Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS)

|

-$299 |

-75.3% |

|

Energy conservation

|

-$191 |

-23.1% |

|

Community development fund

|

-$1,836 |

-41.7% |

|

EPA Clean Water and Drinking Water

|

-$354 |

-19.4% |

|

|

|

|

|

Cuts represent reductions in funding below the Congressional Budget Office’s baseline projection for 2009, which is the level of funding enacted for the program in 2006, adjusted for inflation. For the LIHEAP program, we adjusted CBO’s baseline projections to take into account $1 billion originally provided as mandatory funding for 2007, which was subsequently made available in 2006. The cut in 2009 would be $567 million if that funding were not reflected in the baseline projection. |

To be sure, the bipartisan budget agreement of 1990 and the Clinton budget plan of 1993 also included multi-year discretionary caps. In those plans, however, the caps were set at levels that did not force domestic discretionary cuts nearly this large. Under the Gregg proposal, unless defense and international affairs are funded at levels well below those the President has requested, domestic discretionary programs would have to be cut six times as deeply over the next three years as domestic discretionary programs were cut over the eight years from 1990 – 1998 under the caps in effect during that period.[7]

Moreover, in both 1990 and 1993, the discretionary caps were part of larger, balanced deficit-reduction packages that included tax increases (especially on the most affluent), specific entitlement reductions, and Pay-As-You-Go rules that applied to both tax cuts and entitlement increases. That is not the case here.

3. Terminating programs via a partisan sunset-commission process.

The Gregg bill would establish a panel consisting of 9 Republican and 6 Democratic appointees that would produce a plan calling for various program terminations and realignments. Both entitlement programs and annually appropriated (or “discretionary”) programs could be proposed for termination. Only a simple majority vote of the commission would be needed for the commission to approve a plan. The commission thus could develop its plan on a purely partisan basis.

Congress would then be required to vote on the commission’s plan on a fast-track basis, with 51 (rather than 60) votes being needed to pass it in the Senate. No amendments would be allowed either in committee or on the House or Senate floors.

This highly unusual procedure could be used to ram through program terminations and realignments on a purely partisan basis, without a single vote needed from a member of the minority party at any stage of the process (not in the commission, in Congressional committees, or on the House or Senate floors), and with members of Congress barred even from offering amendments. This element of the Gregg bill would allow terminations that could not be enacted under normal Congressional procedures to be rammed through Congress on a narrow partisan basis.

This process would place much greater restrictions on minority-party members of Congress than the “reconciliation” process does. The reconciliation process is currently the only method whereby legislation can be enacted without extended Senate debate (and therefore on a strictly partisan basis). But the reconciliation process at least permits committee markup of legislation, motions during Senate debate to strike objectionable provisions, and germane Senate amendments as long as they do not reduce savings or add to costs. Furthermore, the reconciliation process does not touch discretionary programs. The Gregg proposal would cover all programs and permit no amendments.

This process also would mean that some programs could be terminated despite having the support of a majority of members of Congress, because they would be included in a package of terminations that would not be subject to amendment. When confronted with an up-or-down vote on the package as a whole, a majority of Members might feel compelled to vote for it.

4. Commission on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.

The Gregg bill would establish a separate commission on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. It would charge this commission with developing a plan to ensure the long-term “solvency” of these programs. As explained below, however, the Gregg bill creates new definitions of “solvency” in Medicare and Medicaid that bear no relationship to the actual financial status of these programs or to how these programs are funded.

The new solvency definitions appear to be laden with ideological overtones. In particular, they would have the effect of restricting — to policy changes more popular on the right end of the political spectrum — the options that could be used with regard to these programs. The Gregg bill would essentially “stack the deck” with respect to what the commission could recommend.

This commission would have 9 members appointed by Republican leaders and 6 members appointed by Democratic leaders. Ten votes would be needed to approve a commission plan.[8] This would create a risk that the commission’s 9 Republican appointees could hang together and seek to entice a lone Democratic appointee to get to 10 votes. The plan the commission produced then would be moved under fast-track procedures in Congress, with 60 votes needed to bring the legislation to a final vote in the Senate.[9] (In this case, amendments to the commission’s proposal would be allowed.) Legislation to make sweeping changes in retirement, health care, and disability programs basic to American life could be developed on a largely partisan basis.

The likely partisan makeup of the commission and the special rules for consideration of its proposal would represent a sharp departure from the workings of the 1983 Social Security commission chaired by Alan Greenspan, one of the few commissions to achieve success in tackling a big problem.

The Greenspan commission had a 8-7 party split in reality as well as name. Of particular note, its recommendations were not insulated by a fast-track procedure. This helped to insure that the Greenspan commission would have to develop a truly bipartisan plan. The commission was careful to conduct its business in such a way that its plan would gain the support of President Reagan, House Speaker O’Neill, and other Congressional leaders of both parties. The commission’s plan succeeded in securing overwhelming bipartisan approval both within the commission itself and then in Congress, and it was enacted through the use of the normal Congressional procedures. In contrast, the commission that the Gregg bill would establish could be used to try to force consideration of and pass partisan legislation that could not be passed under the normal procedures.

The provisions of the Gregg bill that prescribe how the commission would treat Medicare and Medicaid raise particularly serious concerns.

-

Medicaid: The bill would establish a Medicaid “solvency” target that the commission would be charged with developing legislation to meet. The target would be that overall Medicaid costs could not grow faster than the Gross Domestic Product in any year after 2012.

In the absence of a fundamental restructuring of the U.S. health care system, this goal would be virtually impossible to meet without increasingly deep cuts in Medicaid that eventually reached Draconian levels. The reasons for this are clear. The U.S. population is aging. Over time, an increasing share of Medicaid beneficiaries will be elderly people, and elderly people have much higher average health care costs then younger people do. As a result, as the proportion of Medicaid beneficiaries who are elderly increases, the program’s costs necessarily rise at a substantial clip. In addition, the Medicare program does not cover nursing-home costs; among federal programs, only Medicaid does. This will push Medicaid costs still higher as the elderly population grows. Furthermore, per-person health care costs throughout the U.S. health care system — including the private as well as the public sector — are rising faster than the Gross Domestic Product, primarily because of continued medical advances that improve health and prolong life but add to health-care costs. Indeed, Medicaid costs per beneficiary have been rising more slowly in recent years than private-sector health care costs, and studies have established that Medicaid costs per beneficiary are significantly lower than the costs per beneficiary for comparable beneficiaries in the private sector.

The Gregg bill ignores these hard realities. To comply with the Medicaid target that it prescribes would require cuts of extraordinary depth.

-

Meeting the Gregg “solvency” target would require Medicaid cuts of 22 percent by 2020, 36 percent by 2030, and 50 percent by 2042. (These cuts are relative to CBO’s projections of program costs under current law.)

-

It would likely be impossible to achieve cuts of this magnitude — especially in the absence of broader system-wide health-care reform that markedly slows the overall rate of growth of health care costs in the United States, which apparently would be beyond the commission’s charter — without adding millions (and probably tens of millions) of people to the ranks of the uninsured and the underinsured.

-

Indeed, the magnitude of the Medicaid cuts that would be required to meet the Medicaid “solvency” target would be so great that the commission likely would see little alternative to proposing the abolition of Medicaid in its present form and its replacement with a block grant to states under which federal block-grant funding would rise only at the rate of GDP.

-

Medicare: The Gregg bill also would ignore the standard actuarial measure of solvency used in Medicare and substitute a new measure of “solvency” that is based in conservative ideology rather than the program’s financial status. Medicare would be deemed to be insolvent — even if the Medicare trust fund still had hundreds of billion of dollars in assets — once at least 45 percent of total Medicare costs were being financed with general revenues.

The 45-percent threshold is an arbitrary benchmark that is inconsistent with Medicare’s financing structure. By law, Medicare physicians’ coverage and the new Medicare prescription drug benefit are supposed to be financed by general revenues (as well as beneficiary premiums), rather than by payroll taxes. That a particular share of Medicare costs is financed by progressive income taxes (general revenues) rather than by regressive payroll taxes is not itself a problem, just as it is not inherently problematic that defense, education, veteran’s medical care, or space exploration are financed by general revenues. That this 45-percent level is expected to be reached in 2012 also is of little significance. The 45-percent threshold will be reached in a relatively few years even if Medicare costs rise much more slowly than is currently projected.

Of particular concern, complying with the 45-percent threshold would skew debates about how to address Medicare’s financing problems. It would arbitrarily rule out certain approaches to strengthening Medicare’s finances, rather than allowing all approaches to be on the table.

-

The 45-percent measure is designed to preclude increases in general revenues as a way to help finance Medicare. Under this measure, increases in regressive payroll taxes would be allowed, but increases in progressive income taxes would not be.

-

Moreover, if policymakers endeavored to meet the 45-percent threshold without raising Medicare payroll taxes (as many policymakers would want to do), their options would be limited to: increasing beneficiary premiums and co-payments, with the increases growing larger each year and ultimately reaching very high levels; cutting back Medicare eligibility and the medical services that Medicare covers, with such cutbacks growing deeper with each passing year; cutting payments to Medicare providers, with these cuts, too, growing deeper each year; and increasing the amount of “clawback” payments that states are required to make to the federal government in conjunction with the prescription drug program.

To stay within the 45-percent threshold over time, these cutbacks or beneficiary payment increases eventually would have to reach levels that could cause millions of elderly and disabled individuals to become uninsured (if the eligibility criteria were scaled back) or underinsured (if the benefit package were cut extensively), or that could result in many elderly and disabled beneficiaries forgoing care that they need because they can not afford the premiums, co-payments, and deductibles. Alternatively, if the cuts focused heavily on providers, that could essentially cripple Medicare, as many providers likely would cease to accept Medicare patients if they were forced to take big losses on such patients.[11]

In short, the 45-percent standard threatens to artificially skew the Medicare debate by ensuring that progressive revenue options (such as scaling back a portion of the Bush tax cuts for very-high-income households to free up more funding for Medicare) are not permissible options for Congress to consider even as a part of a larger Medicare reform plan. Having to meet this artificial standard would place an even larger share of the burden of dealing with the increases in Medicare costs on increases in premiums, deductibles, and co-payments, increases in payroll taxes, or cuts in eligibility, benefits, and provider payments. The measures that would be permissible generally have one common element: they would largely shield the most affluent Americans and place more of the burden on people on the low and middle rungs of the income ladder.

5. One-sided PAYGO

The Gregg bill also contains a provision that, starting in 2007, would prohibit the Senate from considering any legislation that would increase entitlement spending unless that increase is paid for by cuts in other entitlement spending or increases in revenues.[12] This provision fundamentally differs from the Pay-As-You-Go rules of the 1990s, because tax cuts would be exempt from it.

In addition to failing on equity grounds, this provision is likely to be relatively ineffective as a measure to force fiscal discipline. According to the Government Accountability Office, the tax code contains nearly $800 billion a year in what OMB, GAO, and the Joint Committee on Taxation term “tax expenditures” and former Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan has termed “tax entitlements.” The enactment of a one-sided PAYGO provision would likely spur lobbying efforts to convert many sought-for entitlement expansions into new or expanded tax expenditures, since tax-expenditure measures could continue being deficit-financed.

In fact, this one-sided PAYGO provision could actually have adverse effects on fiscal discipline. It likely would make it harder to pass legislation in subsequent years to reinstate full PAYGO on both tax cuts and entitlement increases. If policymakers who favor tax cuts and seek to curb entitlements can get a PAYGO rule that applies solely to entitlements — without having to apply the rule to tax cuts as well — why should they ever agree to its application to tax cuts? The potential would be gone for an even-handed, middle-of-the-road approach under which those policymakers who favor entitlement increases agree to the imposition of PAYGO on entitlements in return for its application to tax cuts, and policymakers who favor tax cuts accede to the application of PAYGO to tax cuts in return for its application to entitlement expansions.

6. Line-item veto.

The Gregg bill also contains a version of the line-item veto that would open the door to abuse of power by the executive branch. It would run this risk to a greater degree than the version of line-item veto legislation passed by the House on June 22 (which also raises concerns of this nature).

-

The Gregg bill would give the President up to one year after a bill is enacted to propose the cancellation of items in it. By contrast, the 1996 line-item-veto legislation (which the Supreme Court subsequently struck down for other reasons) gave the President 5 days after a bill’s enactment to propose vetoes, and the House Budget Committee’s bill gives the President 45 days. The longer that a President has to submit his vetoes, the greater his ability to threaten to veto various items of importance to particular Members of Congress if they do not vote for proposals that the President is pushing on other, unrelated matters. This lengthy period would increase the prospects that the line-item-veto authority would be used primarily to heighten White House leverage and power rather than to promote fiscal discipline.

-

The Gregg bill would enable the President to cancel funding for programs unilaterally even when Congress has disapproved his vetoes. As noted, the bill gives the President up to a year after enactment of a bill to propose a veto. Once he proposes a veto, he would be allowed to withhold the funds in question for 45 days, regardless of Congressional action. It would not be difficult for a White House to use these procedures to withhold appropriated funds through the end of the fiscal year, so that the funds would lapse — and the appropriation would thereby be cancelled — even if Congress had rejected the veto.

-

The Gregg bill would allow the President to package items from different pieces of legislation (including both appropriations bills and bills dealing with mandatory programs) into a single veto package, and Congress would be required to vote on the package without being allowed to amend it. Congress would have to vote up-or-down on the package as a whole exactly as the President presented it, using fast-track procedures. This would enable the President to take a few egregious pork items (e.g., a new “bridge to nowhere”) that had received damning publicity — and to package vetoes of those egregious items with vetoes of other, much more meritorious items that the President opposed on ideological grounds. Members who voted “no” on the package could then be attacked for refusing to curb the egregious pork.

-

Finally, the Gregg line-item-veto proposal provides for highly disparate (and inequitable) treatment of entitlement expansions and tax cuts. The President would be able to propose a veto of any entitlement increase, even including improvements in Social Security. He would be barred, however, from submitting vetoes of new tax cuts — including special-interest tax loopholes — unless they were specifically classified as “targeted tax benefits” by the Joint Congressional Committee on Taxation. The Joint Tax Committee is a body of Congress whose director is appointed by the chairmen of the tax-writing committees (the Senate Finance Committee and the House Ways and Means Committee). In response to a question on June 14, Senator Gregg said that in deciding whether to classify a new tax break as a “targeted tax benefit” (and thus to make it potentially subject to a line-item veto), the Joint Tax Committee staff “would be responsible to those people who appoint them.” [13] The people who appoint them — the chairs of the tax-writing committees — would, of course, be the very people whose bills contained the tax-cut measures in question. It is likely that few, if any, special-interest tax breaks would be identified as “targeted tax benefits” and made potentially subject to a line-item veto.

In other words, entitlement expansions — such as, for example, a measure to extend health care coverage to more uninsured children — would be subject to a line item veto if a President so chose, but the vast preponderance of new tax breaks for wealthy investors and corporations would be shielded from the line item veto.

Conclusion

This analysis is not intended to be an exhaustive review of the Gregg bill, which also includes other proposals that the Center has analyzed elsewhere (e.g., biennial budgeting[14]) and several minor proposals that would represent sound policy, such as requiring CBO cost estimates of conference reports before the conference reports are brought to a vote. The bill also includes some changes in procedures related to emergency spending that we have not yet analyzed.

The most far-reaching and important proposals are discussed here, however, and they are highly problematic. The bill omits what should be the first three elements of any serious fiscal discipline package: the enactment of actual program reductions and revenue increases, or at least a call for serious bipartisan negotiation to that end; the restoration in full of the PAYGO rule; and the prohibition of the use of the reconciliation process to push through legislation that increases deficits. Instead, the Gregg bill contains provisions that could have profound impacts on American society over time — increasing poverty, swelling the ranks of the uninsured, threatening most domestic programs with reductions, even subjecting disabled veterans to benefit cuts, and adversely affecting the economy when it is weak — while leaving large deficit-financed tax cuts for the most affluent members of society entirely unchecked and permitting their unlimited expansion.

End Notes:

[1] Instead of full estate-tax repeal, we have assumed here the repeal of most (but not all) of the estate tax, as approved by the House of Representatives on July 29, 2006.

[2] This is the amount by which WIC caseloads would have to be reduced under the current program structure, if funding for the program in 2009 were set at the level shown in the President’s budget. The Administration also has proposed shifting part of the costs of the WIC program to states. If that proposal were adopted, the number of people served through WIC would have to be cut 295,000 by 2009.

[3] The need for $1.6 trillion in entitlement caps assumes that in years after 2009, funding for discretionary programs will be held to the 2009 cap level, adjusted only for inflation.

[4] See Richard Kogan, “Proposed Line-Item Veto Legislation Would Invite Abuse by Executive Branch,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised April 21, 2006.

[5] The Gregg bill includes a procedure under which Congressional leaders could, if they chose, expedite a vote to temporarily suspend the GRH-like procedures if CBO projected two consecutive quarters of negative real GDP growth or if the Commerce Department reported that two consecutive quarters with real economic growth of less than one percent (on an annual basis) had already occurred. This procedure, which also existed under the original GRH law, is of little value. CBO never projects recessions before they actually occur. And by the time the Commerce Department issued a report that two very-slow growth (or recession) quarters had occurred, the operation of the GRH-like mechanism (if not evaded through rosy estimates or other gimmicks) likely would have caused damage to an ailing economy, weakening it further.

[6] These estimates assume permanent repeal of most, but not all, of the estate tax, as approved by the House of Representatives on July 29, 2006.

[7] The magnitude of the domestic discretionary cuts that would have to be made under the Gregg caps and the cuts that actually were made in the 1990s are compared here as a share of GDP.

[8] The President, the Speaker of the House, the Minority Leader of the House, and the Majority and Minority Leaders of the Senate would each appoint three members of the commission, with the restriction that no more than two of members each appoint can be affiliated with the same party. Under this plan, the membership of the commission would nominally consist of eight Republicans and seven Democrats, but the Democratic members of the commission appointed by the Republican Leaders are almost certain to be people who agree with the Republican Leaders on all important issues but happen to be registered as Democrats. The Republican members appointed by Democratic Leaders likewise would almost certainly be Republicans in name only. (Recall that the Social Security commission that President Bush appointed in 2001 had a number of Democratic members, but the only Democrats selected were people who agreed in advance to support replacing part of Social Security with private accounts.) Thus, the commission would in reality have a 9-6 partisan majority.

[9] The legislation originally introduced by Chairman Gregg and Majority Leader Frist would have provided for fast-track consideration of the commission’s plan all of the way through final passage, with only 51 votes required to pass the legislation in the Senate. A manager’s amendment adopted by the Budget Committee included a modification to the commission plan that left the fast-track procedures for consideration of the commission’s plan in place (the commission’s plan would be automatically discharged from committees if the committees did not report the proposal and could be brought up in the Senate with the support of 51 Senators instead of 60. In addition, Senate debate on the proposal, and the kind of amendments that could be offered in the Senate, would be limited.) But the manager’s amendment added a requirement for the support of 60 Senators to bring the proposal to a final vote in the Senate. That requirement does not apply to the proposal produced by the sunset commission (described above), which could be passed by the Senate with only 51 votes.

[10] As this brief discussion of Medicaid indicates, in the absence of system-wide health care reform, it will be extremely difficult to achieve large savings in Medicaid without jeopardizing the health care of large numbers of low-income families and individuals. Moreover, even with system-wide reform, limiting the growth of Medicaid costs to the rate of growth of GDP is likely to be impossible without Draconian cuts. Health care reform cannot change the fact that the Medicaid population is aging, the fact that older people have much higher health care costs either than younger people, or the fact that the Medicare program does not cover costs for long-term care, which results in Medicaid being stuck with much of that bill.

[11] The 2006 Medicare trustees’ report projects that under current law, the share of Medicare costs financed with general revenues will rise to 62 percent in 2030. If Congress sought to keep this share at 45 percent without raising payroll taxes or directly hitting beneficiaries (or states) and instead focused entirely on cuts in provider payments, projected Medicare payments to providers would have to be reduced 31 percent by 2050.

[12] Under the Gregg bill, the one-sided PAYGO provisions would become effective once the Medicare trustees reported for two consecutive years that Medicare was projected to reach the 45-percent threshold described above (see previous page) within the next seven years. This trigger would likely be pulled in 2007.

[13] Emily Dagostino, “House, Senate Treat Tax Benefits Differently in Line-Item Veto Bills,” Tax Notes, June 15, 2006.

[14] Robert Greenstein and James Horney, “Biennial Budgeting: Do the Drawbacks Outweigh the Advantages?,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 16, 2006. |