Extending Marriage-Penalty Relief to Working

Poor and Near Poor Families

by Iris J. Lav

Increasing the standard deduction for married couples appeals to a wide range of policymakers who view a standard deduction increase as a targeted way to relieve marriage penalties in the personal income tax. Recently, Rep. Nancy Johnson and Senators Charles Grassley and Dianne Feinstein proposed legislation that takes this approach. A standard deduction increase is relatively well-targeted with respect to income, because the standard deduction is taken primarily by low- and middle-income taxpayers; higher-income taxpayers generally are able to receive a larger deduction by itemizing their expenses.

Nevertheless, a standard deduction increase leaves out a very substantial segment of low- and moderate-income married couples who face large marriage penalties today and could benefit from marriage-penalty relief. This is because it does not provide any relief from the marriage penalties experienced by low- and moderate-income working families that arise from the phase-out of the Earned Income Tax Credit.

Like other features of the tax code, the structure of the EITC creates both marriage penalties and marriage bonuses. EITC marriage penalties occur when two people with earnings marry and their combined, higher income places them at a point in the EITC "phase-out range" at which they receive a smaller EITC (or no EITC at all) than one or both of them would have received if still single. Changes in the standard deduction do not affect the marriage penalties that arise from the EITC structure. Specific, targeted provisions are required to relieve such penalties.

It is possible to craft marriage-penalty relief strategies to address marriage penalties that arise from the EITC phase-out and to do so in conjunction with a standard deduction increase. Several proposals considered in 1998 to provide marriage-penalty relief by increasing the standard deduction for married filers — such as an amendment that Senator Phil Gramm offered to the McCain tobacco legislation and a bill that Reps. Jim McDermott and Richard Neal introduced — included specific provisions that would have extended the benefits of their standard deduction increases to married families receiving the EITC.

It also is possible to craft ways to relieve marriage penalties for both low- and middle-income families that are more efficient than a standard deduction increase. While increasing the standard deduction is relatively well-targeted with respect to income, it is less well-targeted with respect to the marriage penalty problem it seeks to solve. A standard deduction increase is inefficient because it increases marriage bonuses for couples that already receive such bonuses under current law. This makes a standard deduction increase a more costly avenue for relieving marriage penalties than other strategies specifically targeted on families that experience marriage penalties.

Since marriage penalties occur only when both spouses work, marriage penalty relief can be better targeted by providing a deduction for second earners in low- and middle-income families. Legislation introduced by Senate Minority Leader Tom Daschle is an example of this more targeted, less costly approach. Under the two-earner deduction approach as well, the marriage-penalty relief can be extended to working families receiving the EITC.

Marriage Penalties and Marriage Bonuses

Marriage penalties arise when a couple experiences a greater tax liability than it would if the two members were to file as single individuals. These penalties are created by provisions throughout the federal income tax code designed to treat the combined income of joint filers differently than the income of two single filers. The standard deduction is one source of such penalties.

The standard deduction is $4,300 for single filers and $7,200 for joint filers in 1999. Thus, two unmarried people filing as single individuals will have claimed standard deductions totalling $8,600, but must use the joint filer standard deduction of $7,200 after they marry. The smaller standard deduction results in larger taxable income and a higher tax.

A number of marriage penalty reduction proposals a provision to make the standard deduction for joint filers twice the size of the standard deduction for single filers. Most recently, such a provision has been included in "The Tax Relief for Working Families Act" proposed by Representative Nancy Johnson and Senators Dianne Feinstein and Charles Grassley. Had the proposed increase been in effect for 1998, the standard deduction for joint filers would have been $8,600 instead of $7,200.

As Table 1 shows, this provision relieves the marriage penalties that result from the current structure of the standard deduction. If two single people who each earn $15,000 marry, the couple's income tax bill is $210 higher under current law than their total income taxes if they remain single. Increasing the joint filer standard deduction from $7,200 to $8,600 would eliminate this $210 marriage penalty.(1)

Table

1 |

||||||

| Current Law | With Standard Deduction Increase | |||||

| Single | Married | Married | ||||

| Two People Each Earning $15,000 | $2,385 | $2,595 | $2,385 | |||

| Bonus or (penalty) | ($210) | 0 | ||||

| Single Earner Earning $30,000 | $3,443 | $2,595 | $2,385 | |||

| Bonus or (penalty) | $848 | $1,058 | ||||

It should be noted that some couples marry and receive a "marriage bonus." Couples in which only one of the spouses is working generally have marriage bonuses. For example, Table 1 also shows that there would be a tax reduction under current law of $848 if a single person with taxable income of $30,000 married a person who is not working because he or she is in school or caring for a child.(2)

Increasing the standard deduction would increase this couple's marriage bonus from $848 to $1,058. As a result, the disparities between the treatment of dual-earner couples who marry and single-earner couples who marry would be as great under this proposal as under current law.

Marriage Penalties Facing Millions of Families Overlooked

Many low- and moderate- income families have no income tax liability under current law. The combination of their personal exemptions, the standard deduction, the child credit, and (if applicable) the dependent care credit eliminates their income tax liability. As a result, these features of the tax code do not cause marriage penalties for these families. But the structure of the Earned Income Tax Credit affects these families and can cause marriage penalties or bonuses.

The Earned Income Tax Credit for families with children is a refundable credit for low- and moderate-income taxpayers with earnings. The credit is structured so it phases out gradually for families with incomes in excess of a specific level. In 1999, the phase-out range begins when gross income reaches $12,460 and continues through gross income of $26,928 for families with one child and $30,580 for families with two or more children. To the extent that combining the earnings of two people as a result of marriage boosts the couple's income to a point in the phase-out range at which they receive a smaller credit than one or both of them would have received if still single (or raises their income to a level that makes them ineligible for the EITC), the family experiences a marriage penalty.

An EITC-related marriage penalty would occur, for example, if a low-income man married a low-income woman who had similar earnings and was raising two children. Table 2 shows how the marriage penalty comes about for such a man and woman if they each work full time throughout the year at the federal minimum wage. If unmarried, the man would file as a single taxpayer, while the woman would file as a head of household and claim an EITC for her two children. Before they are married, the man pays $549 in income tax while the woman qualifies for a $3,816 refund — the maximum EITC for a family with two children in 1999. Their combined refund thus is $3,267. If they marry, the couple's combined income of $21,424 puts them in the phase-out range of the EITC and reduces their EITC substantially. Their combined refund is reduced from $3,267 to $1,928, yielding a marriage penalty of $1,339. (Note that the EITC, like other features of the tax code, also creates marriage bonuses.(3))

| Man (no children) | Woman (2 children) | Couple (2 children) | |||

| Income | $10,712 | $10,712 | $21,424 | ||

| Exemptions | ($2,750) | ($8,250) | ($11,000) | ||

| Standard Deduction | ($4,300) | ($6,350) | ($7,200) | ||

| Taxable Income | $3,662 | $0 | $3,224 | ||

| Tax (at 15%) | $549 | $0 | $484 | ||

| Child Credit | $0 | $0 | $484 | ||

| Tax after Child Credit | $549 | $0 | $0 | ||

| EITC | ($0) | ($3,816) | ($1,928) | ||

| Liability/(Refund) | $549 | ($3,816) | ($1,928) | ||

| Combined Refund | ($3,267) | ($1,928) | |||

| Marriage Penalty | $1,339 | ||||

Enlarging the standard deduction would, by itself, do little or nothing to address the marriage penalties associated with the EITC. Specific provisions are required to make marriage penalty relief applicable to families receiving the EITC.

A number of marriage penalty reduction proposals considered in 1998 did address the marriage penalties resulting from the EITC phase-out, using one of two general approaches.

- One approach is to reduce, through a deduction that applies to the EITC computation, the amount of income that married couples must count for the purposes of calculating the EITC phase-out.

- The other approach is to modify the structure of the EITC so the phase-out begins (and ends) at a higher income level for married couples than for taxpayers who are not married.

In either case, the effect is to increase, relative to current law, the amount of EITC a married couple can receive when its income falls in the phase-out range of the EITC schedule.

The first approach was taken by Senator Phil Gramm in his amendment to the McCain tobacco legislation. Senator Gramm proposed an amendment that would increase the standard deduction for married couples with incomes below $50,000 by $3,450. Under the Gramm amendment, the standard deduction for a married couple would be increased to equal the sum of the standard deduction for a single filer and the standard deduction for a head-of-household filer. The Gramm amendment also included specific language to apply the additional deduction to the EITC computation.

The Gramm proposal effectively increases the income level at which the EITC phase-out begins by changing the definition of income for purposes of the EITC phase-out. Under current law, the income used to determine where in the phase-out range a family falls is the family's adjusted gross income or total earnings, whichever is larger. In the Gramm proposal, a married-couple family's adjusted gross income or earnings for EITC purposes would be reduced by the amount that the standard deduction for married couples is being increased.(4)

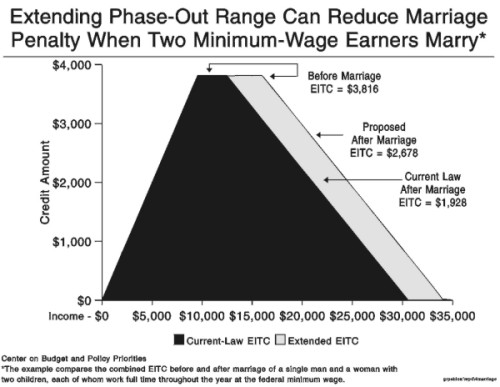

The second approach, modifying the EITC structure for married couples, was proposed by Reps. Richard Neal and Jim McDermott.(5) The Neal/McDermott bill would create a separate EITC computation for joint filers that increases the amount of income the couple can earn before the EITC begins phasing out. The phase out begins when income reaches $12,460 under current law for 1999; the Neal/McDermott approach would raise the beginning of the phase out for joint filers to approximately $16,000. This change was intended to be used in conjunction with a separate bill increasing the standard deduction for joint filers.

Raising the beginning of the phase out range means that married-couple families with incomes up to approximately $16,000 would be able to receive the maximum EITC. In addition, EITC-eligible married families with incomes above that level would receive somewhat larger EITCs than under current law; married families with incomes up to $30,000 would see an EITC increase of approximately $750. And the income level at which the EITC is fully phased out would increase from $30,580 to over $34,000. (See Figure 1.)

The

effect of the two approaches — allowing a subtraction from income for calculating the

EITC phase out and modifying the structure of the EITC for married couples — is

substantively the same. In either case, couples in the phase-out range would receive

somewhat larger EITCs for any given income level, and the income level at which the EITC

is completely phased out for married couples would rise.

The

effect of the two approaches — allowing a subtraction from income for calculating the

EITC phase out and modifying the structure of the EITC for married couples — is

substantively the same. In either case, couples in the phase-out range would receive

somewhat larger EITCs for any given income level, and the income level at which the EITC

is completely phased out for married couples would rise.

EITC marriage penalty relief in the amount provided by either the Neal/McDermott or Gramm approaches to a standard deduction increase would likely cost close to $3 billion a year. Providing a different level of relief obviously could increase or decrease that cost. For example, the Johnson/Grassley/Feinstein proposal increases the standard deduction by approximately $1,400 (to double the standard deduction applicable to single taxpayers). If the same size deduction were applied to the EITC calculation, the cost likely would be less than $1.5 billion a year.

Two-Earner Deduction is More Efficient

As noted, a standard deduction increase is not targeted in the most efficient way with respect to the marriage penalty problem it seeks to solve. Increasing the standard deduction for joint filers increases marriage bonuses for couples that already receive such bonuses under current law. It maintains the differential tax treatment of married couples that have the same total earnings but different earnings patterns (ie., one-earner versus two-earner families). As a result, a standard deduction increase is a more costly avenue for relieving marriage penalties than other strategies specifically targeted on families that experience marriage penalties.

| Two-Earner Families - Each spouse earns at least one-third of couple's total earnings | Married Families - Only one spouse has earnings | |

| Penalties | $15.2 | $0 |

| Bonuses | 0.1 | 28.5 |

| Source: Congressional Budget Office | ||

In addition, because a standard deduction increase maintains the disparities that exist under current law between couples that enjoy marriage bonuses and other married couples, it could sow the seeds of demands for future tax relief to redress the disparities.

It is possible to target marriage penalty relief much more effectively and efficiently on low- and middle-income families that currently experience marriage penalties. Table 3 shows couples in which only one member works or in which one member earns most of the couple's income have substantially lower taxes after marriage than before; these couples enjoy marriage bonuses under current law and do not need marriage penalty relief. By contrast, two-earner couples in which each spouse earns at least one-third of the couple's overall earnings generally pay higher taxes when married than when single. (Other families may have marriage penalties or marriage bonuses, depending on income and other circumstances.) Consequently, it is most efficient to target marriage penalty relief to couples in which there are two earners.

Legislation that Senate Minority Leader Tom Daschle has introduced, for example, would accomplish such targeting by allowing a deduction of 20 percent of the lower-earning spouse's earnings, phased out for couples with adjusted gross income exceeding $50,000.(6) For families receiving the EITC, the Daschle bill allows the second-earner deduction to be used to reduce the earnings and adjusted gross income counted for purposes of computing the EITC phase-out, much as the Gramm proposal does for his standard deduction increase.

A standard deduction increase that boosts marriage bonuses will cost much more than a marriage-penalty relief strategy targeted on couples that experience marriage penalties. The difference in cost can be readily illustrated. The standard deduction increase proposed by Senator Gramm in 1998 would cost approximately $9 billion a year. The Daschle second-earner deduction, on the other hand, would cost approximately $3 billion a year, a third as much. Both proposals include relief of EITC marriage penalties, and both proposals would phase out their tax relief for families with incomes exceeding $50,000. Although the Gramm proposal provides greater tax reduction to some families, the major difference in cost between the two proposals results from the difference in whether couples that already enjoy marriage bonuses under current law would have those bonuses enhanced.

Conclusion

Raising the standard deduction for married couples without including specific provisions to apply the higher deduction to the EITC phase-out computation would aid many middle-income families that have marriage penalties under current law. This approach, however, would miss millions of low- and moderate-income working families that also face marriage penalties. The standard deduction increase could be made more equitable through inclusion of a specific provision allowing the deduction also to deliver EITC marriage penalty relief.

Increasing the standard deduction for married couples would, however, cost substantially more than is necessary to provide effective marriage penalty tax relief to low- and middle-income families need entail, because it also showers tax relief on millions of couples that already receive marriage tax bonuses, making those bonuses larger. A more efficient approach is a targeted two-earner deduction that includes provisions for applying the deduction to the EITC computation.

End Notes:

1. If one of the two single people qualifies to file as a head of household, the marriage penalty would be larger. The standard deduction for head of household filers in 1999 is $6,350. When added to the single standard deduction of $4,300, the total standard deduction for these two people is $10,650. This would compare to a joint filing standard deduction of $7,200 after marriage. In this case, the marriage penalty is $518.

2. Before marriage, the $30,000 earner was entitled to a standard deduction of $4,300 and a personal exemption of $2,750. The non-working member of the couple did not have income and so could not use either the standard deduction or the personal exemption for which he or she otherwise would be eligible. After marriage, the couple's income would still be $30,000. While income would remain constant, the couple would be able to use the $7,200 standard deduction for married couples instead of the $4,300 standard deduction for single individuals and would be able to subtract two personal exemptions rather than one. This would result in lower taxable income after marriage than before and thus a lower tax.

3. When a person raising a child has little or no earnings and marries a worker with modest earnings, the family can become newly eligible for an EITC or eligible for a larger EITC and thus receive a sizeable marriage bonus. Consider, for example, the father and mother of two children who are not married and live apart. The mother stays at home to care for the children and does not work; she may live with her parents or receive welfare payments. Since the mother does not have earnings or other taxable income, she pays no income tax and receives no EITC. The father works but cannot receive the EITC for his children because he does not live with them. If the father earns $21,400 a year, he would pay $2,153 in income tax. If he marries the mother of his children, however, the family would receive a $1,933 refund. In this case, marriage results in a marriage bonus of $4,086, nearly half of which is due to the EITC.

4. Specifically, the language says, "Section 329(c)(2) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 (defining earned income) is amended by adding at the end the following new subparagraph: '(C) Marriage Penalty Reduction. — Solely for purposes of applying subsection (a)(2)(B), earned income for any taxable year shall be reduced by an amount equal to the amount of the deduction allowed to the taxpayer for such taxable year under section 222 [the additional standard deduction for couples].'"

5. The 1998 bill was H.R. 3995.

6. This provision was first introduced in 1998 during consideration of tobacco legislation in the Senate. It was reintroduced as part of S. 8, the "Income Security Enhancement Act of 1999," in January 1999.