New Tax-Cut Law Ultimately Costs as

Much as Bush Plan

Gimmicks Used to Camouflage $4.1 Trillion Cost in Second Decade

by Joel Friedman, Richard Kogan, and Robert Greenstein

| PDF of full report If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

The tax-cut legislation that President Bush signed into law on June 7 includes unprecedented maneuvers that enable the law to comply with the $1.35 trillion tax-cut limit the Congressional budget plan sets for the years from 2001 through 2011. This apparent compliance with the budget resolution targets, however, is essentially a fiction; in reality, the new tax-cut law substantially exceeds these targets. The tax-cut law complies on paper with the budget targets only because all of the tax cuts in the legislation sunset — or expire — at the end of 2010; as a result, the new law is able to meet an 11-year target by simply leaving out much of the last year's costs. The new law also leaves out major tax-cut provisions whose enactment is inevitable, such as extension of the research and experimentation credit and measures to address serious problems in the Alternative Minimum Tax. In other words, the conferees artificially reduced the official cost of the new law by sunsetting the tax cuts before the end of the eleven-year budget period and omitting inevitable costs. They then used the money these maneuvers freed up to write even more tax cuts into the legislation.

Compared to the Senate version of the bill, the enacted tax-cut law directs nearly all of the extra funds created by sunsetting the tax cuts after 2010 to tax cuts for those with high incomes — such as reducing the top rate to 35 percent (rather than 36 percent, as in the Senate bill) and completely eliminating the limitation on itemized deductions for very high income taxpayers. (The Senate bill retained the limitation on deductions for those with incomes above $245,000.) (See a separate Center analysis for a discussion of the distribution of the tax-cut benefits in the new law.(1))

The official Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) cost estimate of the tax-cut law shows a cost of $1.349 trillion over 11 years. This estimate is misleading, however, as a newly released JCT estimate makes clear. The gimmicks used in the new tax-cut law hold down costs over the 11-year period covered by the budget resolution, but yield little or no permanent savings over the long term. Once the reasonable assumption is made that these tax cuts continue beyond the sunset date, their costs are seen to explode.

- If the cost of the new law were not artificially lowered by leaving out various tax-cut measures whose enactment is inevitable and by relying on artificial sunsets, it would cost $1.8 trillion over the 11 years from 2001 through 2011. This is likely to be the true cost.

- To this figure must be added the increased interest payments on the debt that will have to be made as a result of the tax cut. Counting the interest costs, the overall price tag is $2.3 trillion. In other words, the tax cut will consume a total of $2.3 trillion of the budget surpluses projected for the 11-year period. This is slightly more than the total cost of the Bush tax-cut proposal (see box on page 6).

- In the following ten-year period from 2012 to 2021 — when all of the provisions of the legislation will be fully in effect — the cost will be approximately $4.1 trillion, before adding the cost of the increased interest payments. (See appendix for a discussion of the methodology for estimating the cost in the second ten years.)

The new tax law incorporates virtually every device that the Administration's tax-cut proposal or the House or Senate tax bills employed to hold down costs artificially in the first eleven years, while adding to them the gimmick of sunsetting the entire bill after 2010. Overall, the new tax-cut law appears to contain more budget gimmicks than any tax bill — and quite possibly any piece of major legislation — in recent history. These gimmicks include the following:

- Most of the major tax cuts are phased in slowly, with some becoming fully effective only in January 2010 — or only 12 months before they are terminated as a result of the artificial sunset.

- To make the bill's costs appear lower, other provisions sunset even sooner than 2010, even though virtually everyone knows they will have to be extended. For example, the bill sunsets after 2004 a provision that provides some relief from the burgeoning Alternative Minimum Tax.

- Some of the tax cuts do not even begin to take effect for a number of years.

- One provision related to corporate revenues is purely a timing shift, moving tens of billions of dollars in receipts between years but making no substantive change.

- Finally, the new law leaves out altogether various major tax-cut measures that are virtually certain to be enacted in the near future, such as the extension of the Research and Experimentation tax credit and legislation to address on an ongoing basis the serious problems in the Alternative Minimum Tax, which this new law aggravates (and consequently makes more expensive to remedy).

Provision |

When Provision Becomes Fully Effective | When Provision Sunsets |

Years Fully Effective Before Sunsetting |

| Repeal estate tax | Jan. 1, 2010 | Dec. 31, 2010 | 1 year |

| Repeal personal exemption phase-out | Jan. 1, 2010 | Dec. 31, 2010 | 1 year |

| Repeal itemized deduction phase-out | Jan. 1, 2010 | Dec. 31, 2010 | 1 year |

| Expand child credit | Jan. 1, 2010 | Dec. 31, 2010 | 1 year |

| Benefits for married couples: | |||

| Increase standard deduction | Jan. 1, 2009 | Dec. 31, 2010 | 2 years |

| Expand 15% bracket | Jan. 1, 2008 | Dec. 31, 2010 | 3 years |

| Expand EITC for married filers | Jan. 1, 2008 | Dec. 31, 2010 | 3 years |

| Deduction for higher education expenses | Jan. 1, 2004 | Dec. 31, 2005 | 2 years |

| Increase IRA contribution limits | Jan. 1, 2008 | Dec. 31, 2010 | 3 years |

| Increase AMT exemption | Jan. 1, 2001 | Dec. 31, 2004 | 4 years |

| Increase employee contribution limit for 401(k) and similar retirement plans | Jan. 1, 2006 | Dec. 31, 2010 | 5 years |

| Reduce upper-bracket income tax rates | Jan. 1, 2006 | Dec. 31, 2010 | 5 years |

| Note: Period covered by the congressional budget resolution: 11 years | |||

The result, as noted, is a cost explosion in the second ten-year period. It is in this period, which falls outside the period the budget resolution covers, that the nation's fiscal situation becomes tenuous as the baby-boom generation begins to retire in large numbers. In fact, the Comptroller General of the United States (the head of the General Accounting Office) recently testified that "although the 10-year horizon looks better in CBO's January 31 projections than it did in July 2000, the long-term fiscal outlook looks worse" (emphasis added).(2) The long-term forecast has deteriorated due to adoption of a higher (and, most analysts believe, a more realistic) estimate of the long-term rate of growth in health care costs. This change for the worse in the long-term projections suggests that the room available for permanent tax cuts or spending increases has gotten smaller, not larger, as compared with previous budget projections. Relying on an array of gimmicks to shrink the apparent cost of tax cuts in the first ten years — and thereby making the total tax-cut package larger and ultimately much more costly than it otherwise would be — only makes the long-term fiscal situation more troublesome.

The Sunset in 2010

There is no policy reason for the tax cuts in the new law to sunset in 2010. This gimmick is employed for the sole purpose of holding down costs in 2011 and thereby accommodating more tax cuts within the period covered by the budget resolution. (A sunset is required by the Congressional Budget Act of 1974. To comply with the Budget Act, however, the sunset need only take effect at the end of 2011. That approach, which does not significantly affect the measure's eleven-year costs, was the approach the Senate-passed bill took.)

Supporters of the legislation clearly expect these tax cuts will not actually expire after the end of 2010, but will remain in effect. Indeed, any lawmakers who do not favor extending the tax cuts when the time comes to renew them can anticipate being subject to political attack for "seeking to impose major tax increases on the American people." House Majority Leader Dick Armey has announced that the House will shortly consider legislation to extend the tax cuts permanently, even though such an extension would breach the targets set in the congressional budget plan.

The New Law Backloads Most of its Major Tax Cuts

Under the new tax-cut law, several provisions do not become fully effective until 2010 — the same year in which they are repealed by the bill's sunset provision. The estate tax would not be repealed until 2010. Nor would repeal of the personal exemption phase out for high-income taxpayers ("PEP") and the limitation of itemized deductions for high-income taxpayers ("Pease"), or the last stage of the increase in the child tax credit, become fully effective until 2010. As a result, these provisions are in full effect for only 12 months before they terminate.

In other cases, the dates on which provisions become fully effective are not only delayed until late in the decade, but some of these tax cuts do not start phasing in until mid-way through the period. For instance, the major marriage-penalty relief provisions in the new law would not start phasing until 2005. Similarly, the repeal of "Pease" and "PEP" would not begin to phase in until 2006. By comparison, President Bush had proposed that all major tax cuts become fully effective by 2006, except for estate tax repeal, which would have occurred in 2009.

In historical terms, the new tax-cut law is unprecedented in the way which it delays implementation of tax cuts. The Reagan tax cuts were largely phased in after three years. Although some of the tax cuts enacted in 1997 phased in slowly, such as the increase in the estate tax exemption, that legislation did not wait several years before beginning to implement major tax cuts.

The New Law Uses the AMT to Hold Down Costs Artificially

The tax-cut law makes the growing problems surrounding the Alternative Minimum Tax more severe. It also understates the cost of a number of its tax-cut provisions by unrealistically assuming that the AMT will cancel out several hundred billion dollars of tax relief the new tax-cut law is designed to provide.

The AMT requires a set of calculations that are separate and distinct from regular income tax calculations. Taxpayers are required to pay the higher of their regular income tax or their AMT liability. The reductions in income tax rates in the new tax law would lower regular income taxes substantially and thereby greatly increase the number of taxpayers whose AMT liability (in the absence of reductions in the alternative tax) will be higher than their regular tax liability.

- To address this problem, the new law provides limited — and largely temporary — AMT relief; it increases the AMT exemption amount but ends that provision after 2004. As a result, much of the limited AMT relief the bill provides would terminate after 2004.

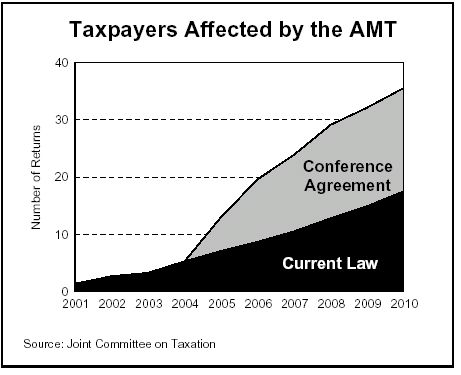

- The Joint Tax Committee projects that under the bill, the number of taxpayers affected by the AMT would explode over the coming decade, climbing to 35.5 million taxpayers by 2010 — a higher level than either the Administration, House, or Senate measures would have reached in that year. This is 25 times the number of taxpayers the AMT will affect in 2001.

- Joint Committee estimates indicate that a swollen AMT will cancel significant amounts of the tax relief that the bill is commonly thought to provide, thereby lowering the bill's stated cost by more than $300 billion over the first decade.

Congress is unlikely to allow the AMT to explode in this manner. This growth in the AMT is neither in keeping with the AMT's original policy intent nor politically sustainable. Congress ultimately will act to prevent these tax cuts from pushing millions more taxpayers — including substantial numbers of middle-class taxpayers — under the AMT. Such action will cost tens of billions of dollars on an annual basis. By leaving permanent AMT reform out of the new tax-cut law except for a few modest measures, the framers of the proposal were able to shrink substantially the official cost estimate of the proposed tax cuts. But since the problems in the AMT eventually will be addressed, the actual cost of the new tax-cut law ultimately will be considerably greater than the figures reflected in the current official cost estimate.

The New Law Fails to Extend Several Expiring Tax Credits That Are Virtually Certain to Be Extended

Although both President Bush and the Senate proposed to make permanent the Research and Experimentation tax credit — and there is near-universal agreement that this popular tax credit, scheduled to expire in 2004, will be renewed — the new tax-cut law fails to extend it. That enables the $47 billion cost of extending this credit throughout the decade — a cost that is included in the Bush plan and ultimately will be incurred — to be left out of the bill's cost estimate. The new law also omits measures to extend most of the other popular tax credits that are scheduled to expire in the next few years. These credits virtually always are extended; most of them are certain to be renewed in the years ahead. Extending these credits through 2011 will cost another $34 billion. This cost, too, is not reflected in the JCT's official estimate of the tax cut's cost.

The New Law Adds to the List of "Tax Extenders" by Sunsetting Some of its Tax-cut Provisions Even Before 2010

Although the new tax-cut law sunsets all provisions in 2010, some provisions expire at an even earlier date under the new law. These include: an "above-the-line" deduction for qualified higher education expenses, which sunsets in 2005; a non-refundable credit for moderate-income workers to encourage retirement savings, which sunsets in 2006; and the increase in the AMT exemption discussed above, which sunsets in 2004. It is highly unlikely these tax provisions will be allowed to expire; they almost certainly will be extended. Not counting the increase in the AMT exemption (which is considered as part of the AMT discussion here), extending these new Senate provisions throughout the decade would add $26 billion in costs. Stated another way, sunsetting these provisions artificially lowers the bill's cost by another $26 billion.

Tax Cut Consumes $2.3 Trillion of Projected Surplus When Interest is Taken Into Account In discussing the full effect of any tax or spending proposal on the projected surplus, it is necessary to reflect the fact that increased costs will directly reduce the projected surplus, and by doing so, lead to higher debt — and therefore higher interest costs — than CBO projected when making its estimate of the surplus. The table below shows the full cost over the first decade of the basic Bush tax package and the new tax-cut law, with and without these resulting interest costs. (The new tax law produces slightly higher interest costs than the Bush tax-cut proposal because the new tax law includes some features that provide immediate tax cuts, including rebates. Since these tax cuts take effect sooner than President Bush had proposed, the resulting increases in interest costs compound over a longer period of time.)

|

Do Further Tax Cuts — and an Explicit Busting of Budget Targets — Lie Ahead?

By relying on these various devices to hold down the cost of the tax-cut package, conferees were able to circumvent much of the fiscal discipline the Congressional budget resolution targets are supposed to impose. Moreover, the White House and Republican Congressional leaders have said they hope to pass additional tax cuts in coming months, beyond the tax-cut measures in the newly enacted law, and do not consider the budget resolution's tax-cut limit a binding constraint. The Administration's budget includes numerous tax-cut proposals that are not included in this legislation, and the President recently proposed additional new tax cuts as part of his energy policy.

House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Bill Thomas was recently quoted in the Daily Tax Report as saying he is "operating under no limit whatsoever" when it comes to passing tax-cut bills this year. Chairman Thomas' comments have been echoed by other members of the Republican leadership in the House and Senate. The leadership's approach appears to be to seek to write tax cuts into minimum-wage legislation, Patients' Bill of Rights legislation, and possibly other popular legislation that may be able to secure the 60 votes needed in the Senate to breach the budget resolution targets.

Appendix

Method of Projecting the Cost of Tax Cuts

We project the cost of the tax cuts into the second decade by generally assuming that their costs in the second ten years, measured as a share of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), are the same as their costs in 2011. That is, we assume that tax cuts will grow at the same pace as the economy after 2011. This is the standard approach for projecting revenues over longer periods of time. CBO uses it when making long-term budget projections.

To derive the full costs in 2011, we take the official Joint Tax Committee estimate of the costs of the new law in 2011 and add to it the recent JCT estimate of the costs that will be incurred in 2011 if the sunsets in the legislation are removed, AMT relief is provided so the legislation does not increase the number of taxpayers subject to the AMT, and the other expiring tax credits (such as the Research and Experimentation credit) are extended.

There is no JCT estimate of the cost of AMT relief that would be associated with the President's proposed tax-cut package. To estimate the cost of the associated AMT relief under the President's tax package, we use the following approach. First, we compute for each year the amount of AMT relief that the JCT has estimated is needed for each additional taxpayer who will be subject to the AMT as a result of the new tax law. Second, we apply this per-capita cost of AMT relief to the JCT estimate of the number of additional taxpayers who would be subject to the AMT each year under the President's tax package.

Our methodology includes one exception to the general approach of assuming that revenue losses grow with GDP; this exception applies to our methodology for estimating the cost in the second ten years of repealing the estate tax. Before enactment of the new tax law, JCT estimated that revenues collected by the estate tax would grow slightly faster than GDP after 2006. That growth probably reflected the fact that under prior law, the amount of an estate that was exempt from taxation was not indexed for inflation; as estates grew with inflation, a greater share of their assets thus would have become subject to the estate tax. We assume that the revenue loss that will result from repeal of the estate tax will grow after 2011 at the same rate (relative to GDP) as JCT projected that estate tax revenues would have grown between 2007 and 2011 under prior law.

Also of note, estimates from the JCT show that the President's proposed repeal of the estate and gift tax would have resulted in the loss not only of the revenue that otherwise would have been derived from this tax but also of some income tax revenue, as well. The reason is JCT's conclusion that without the estate and gift tax, wealthy individuals would engage in asset-shifting schemes that would shield some of their income from taxation. We assume that the portion of the cost of the President's estate-and-gift-tax repeal proposal attributable to lost income tax revenue would have grown with GDP after 2011, rather than growing slightly faster than GDP.

End notes:

1. See "Under Conference Agreement, Dollar Gains for Top One Percent Essentially the Same as Under House and Bush Packages," available at www.cbpp.org/5-26-01tax2.htm.

2. Long-Term Budget Issues: Moving from Balancing the Budget to Balancing Fiscal Risk, Testimony of Comptroller General David M. Walker before the Senate Budget Committee, February 6, 2001.