|

Revised May 22, 2008

CLAIMS THAT A MODEST TAX SURCHARGE ON MILLIONAIRES WOULD DAMAGE SMALL BUSINESSES AND THE ECONOMY DO NOT WITHSTAND SCRUTINY

By Aviva Aron-Dine

Supplemental appropriations legislation that the House of Representatives approved last week (H.R. 2642) would impose a modest income tax surcharge on couples with adjusted gross income above $1 million (and singles with AGI above $500,000) to fund an expansion of higher education benefits for veterans.[1] The surcharge would be equal to 0.47 percent of a taxpayer’s income above the threshold. For example, a couple with AGI of $1.1 million would pay a surcharge of $470 ($470 = 0.47% x $100,000).

Critics of the legislation have charged that the surcharge would harm small businesses and thereby damage the economy. In a letter to House members, the National Association of Manufacturers asserted that the surcharge would even diminish the employment prospects of returning veterans.[2] The claim is that, because most small business owners pay individual income tax on their small business income, many of them would pay higher tax on their profits as a result of the legislation, which would deter them from hiring new workers and investing in their businesses. This argument is severely flawed in several respects.

Only a Tiny Number of Small Businesses Would Pay the Surcharge

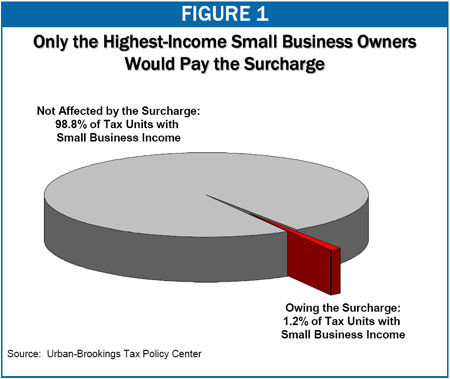

Data from the Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center show that only 1.2 percent of all tax units with business income have incomes high enough for them to owe the surcharge. (See Figure 1.) Critics of the House-passed bill maintain that their concern is its impact on “mom and pop” small business operations, which they describe as the engines of economic growth and job creation. These critics should be reassured by the fact that the overwhelming majority of such enterprises will never generate enough profits to make them subject to the surcharge. (Importantly, only business profits, not gross receipts, are potentially subject to the surcharge. Some critics have misleadingly implied that the surcharge applies to gross receipts over $1 million.)

Moreover, even the 1.2 percent figure likely overstates the impact of the surcharge on small business owner-operators. The Tax Policy Center data classify as a small business owner anyone who receives any income from an S corporation, partnership, sole proprietorship, or various other types of businesses.[3] Many of these individuals, however, play no role in managing the business and are simply passive investors who contribute some capital to the enterprise and, in exchange, receive a share of the profits. Their ranks include President Bush and Vice-President Cheney, as well as many other wealthy investors who are not actual small business operators — and whom the public generally does not think of as “small business owners.” These individuals typically receive the bulk of their incomes from other sources. The Tax Policy Center data show that the households with business income that would pay the surcharge receive, on average, less than one- third of their income from small businesses. The notion that a business’s day-to-day hiring and investment decisions would be greatly affected by a small increase in the tax rate that these passive investors face strains credulity.

Also of note, some of the businesses affected are far from small. Joint Committee on Taxation data show that while 82 percent of all S corporations, partnerships, and sole proprietorships had gross receipts of less than $100,000 in 2003, some 58 percent of these businesses’ total business receipts went to the small share of businesses whose gross receipts exceeded $10 million.[4] Such businesses better resemble large corporations than the popular image of a “small business.” Because these enterprises are organized as S corporations, partnerships, or sole proprietorships, however, their income is generally taxed at a lower effective tax rate than the earnings of comparable businesses that are organized as C corporations. This would remain the case even if the House-passed income tax surcharge were enacted.

Economic Effects of the Surcharge Would Be Minimal

As discussed above, the surcharge would affect only a tiny fraction of small business owners. And it is unlikely to significantly affect the business decisions of even the few small businesses that would pay it.

In the short term, with the economy experiencing either a recession or a significant slowdown, the main determinant of business investment and hiring decisions will be consumer demand. Whatever the tax rate on their profits, businesses will hire new workers only if they are confident they will be able to sell what those workers produce. As a Goldman Sachs analysis explains, “companies don’t spend money just because it’s there to spend. To justify outlays for new projects, the expected returns have to exceed the costs, and that usually requires growth in demand strong enough to put pressure on existing resources.”[5] The House-passed surcharge is highly unlikely to depress overall consumer demand, since it affects only a small number of very high-income households and since these high-income households would more likely have saved than spent the additional income anyway. The surcharge thus is unlikely to affect business hiring decisions in the near term.

Over the longer run, it is possible that tax rates might influence business owners’ decisions about whether to invest money in expanding their businesses. But the impact is likely to be very modest, particularly since the surcharge itself is so small. As compared with the surcharge, the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts affected a much larger share of the population and changed marginal tax rates by much larger amounts. (Just the reduction in the top marginal rate enacted in 2001 was almost ten times as large as the proposed tax surcharge, and it affected more people.) But when the Treasury Department examined the economic effects of extending the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts, taking into account their impact on investment, it found these effects would at best be quite small — the equivalent of increasing real annual economic growth from 3 percent to 3.04 percent.[6]

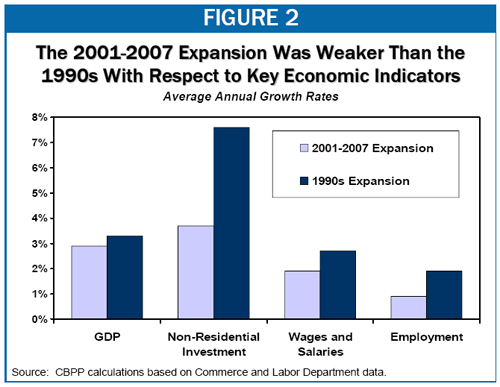

Indeed, recent history alone should be enough to discredit the dire pronouncements that opponents are making about the surcharge. For instance, for the surcharge to meaningfully affect the job prospects of returning veterans, it would have to have a very large impact on aggregate investment and economic growth. And if tax rates really had economic effects this large, these effects should be evident from aggregate economic data: the economy should perform notably better when tax rates are low than when tax rates are high. But, as Figure 2 shows, aggregate economic growth, employment growth, investment growth, and wage and salary growth all were stronger in the 1990s, when the top individual income tax rate was 39.6 percent, than during the 2001-2007 expansion, after the top rate had been cut. Furthermore, the performance of these economic indicators also was stronger in most or all other post-World War II business cycles than during the recent expansion, despite the fact that marginal tax rates on high earners were much higher in the previous business cycles than they are today (or than they were in the 1990s).

Surcharge Would Take Back Only a Small Fraction of the Tax Cuts Received by the Highest-Income Americans

Tax Policy Center estimates show that if the House-passed surcharge takes effect in 2009, only 500,000 filers —just 3 in 1,000 U.S. households — will be affected.

These very high-income households have been among the largest beneficiaries of the tax cuts enacted over the past several years. For example, the Tax Policy Center estimates that, in 2009, households with total income over $1 million will receive an average of $124,000 in tax cuts from the tax reductions enacted in 2001 and 2003. The surcharge that these households would pay under the House bill, in contrast, would average only about $9,000 — or just 7 percent of their average tax cut. (See Table 1.)[7]

|

Table 1: Average Tax Cuts and Surcharge Payments for Households With Incomes over $1 Million, 2009 |

|

Tax Cut from Tax Reductions Enacted in 2001 & 2003 |

$124,000 |

|

|

Surcharge |

|

$9,000 |

|

|

Net Tax Cut After Surcharge |

$115,000 |

|

|

Source: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center |

Tax Policy Center estimates show that had the House-passed surcharge been in effect in 2007, fewer than 400,000 filers — and fewer than 3 in 1,000 U.S. households — would have paid it. Since the surcharge raises about $5 billion per year and is levied at a 0.5 percent rate on AGI above $1 million for couples and $500,000 for singles, this implies that households subject to the surcharge have incomes that average about $2.5 million above those thresholds: about $3.5 million for a couple.

End Notes:

[1] More specifically, the surcharge applies to “modified AGI,” which differs from AGI in minor respects.

[2] “NAM Key Vote Letter on Amendment 3 to the Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2008,” May 15, 2008.

[3] More specifically, the Tax Policy Center definition includes any filer with income reported on tax schedules C, E, or F. The Tax Policy Center uses this definition so that its estimates are comparable to those issued by the Treasury Department.

[4] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Present Law and Background Relating to Selected Business Tax Issues,” JCX-41-06, September 19, 2006, http://www.house.gov/jct/x-41-06.pdf.

[5] GS Weekly, September 21, 2007.

[6] See Jason Furman, “Treasury Dynamic Scoring Analysis Refutes Claims by Supporters of the Tax Cuts,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised August 24, 2006, https://www.cbpp.org/7-27-06tax.htm.

[7] Even if these tax cuts were allowed to expire at the end of 2010, it would be many years before the surcharge took back even full value of the tax cuts that very high-income households have already received. |