FOOD

STAMP OVERPAYMENT ERROR RATE HITS RECORD LOW

by

Dottie Rosenbaum

| PDF of this report |

| If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

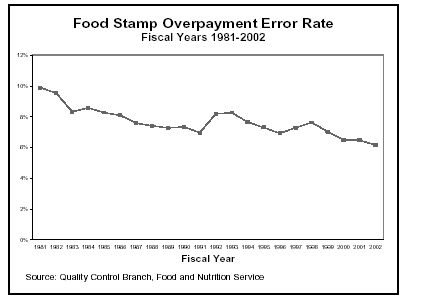

On June 27, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) released state and national food stamp error rates for federal fiscal year 2002 calculated through the food stamp quality control (QC) system. The national overpayment error rate — the percentage of food stamp benefit dollars issued in excess of the amounts for which households are eligible — fell by a third of a percentage point from 2001 levels to 6.16 percent, the lowest level since USDA began the current system of measuring error rates in 1981. The underpayment error rate fell to 2.1 percent, also the lowest level on record. The combined payment error rate, which is calculated by summing the overpayment and underpayment error rates, fell to an all-time low of 8.26 percent.

Nonetheless, the number of states subject to fiscal penalties based on their error rates rose from fifteen to twenty. This is because the food stamp QC sanction system for 2002 measures states’ performance relative to the national average, ensuring that large numbers of states will be subject to sanctions even when overall performance among the states improves.

In May 2002, as part of the nutrition title of the farm bill, the President signed legislation that changes the system for assessing fiscal sanctions against states, beginning with the 2003 error rates. The new system will focus monetary penalties on the few states with persistently high error rates instead of on a large number of states with minor problems. This reform of the QC sanction system should lessen the pressure that states feel to adopt policies that impede access to the Food Stamp Program. The QC system nonetheless will remain the most sophisticated system for measuring payment accuracy in any major federal public benefit program and will continue to be a critical tool for measuring and monitoring state stewardship of federal food stamp funds.

USDA also released states’ error rates for cases in which they denied or terminated benefits. (The underpayment error rate includes only cases where states gave some benefits, but not as much as the household should have received under food stamp rules. It does not include actions that completely denied food stamps to eligible low-income households.) Nationally, in about eight percent of the instances in which households were denied food stamps or terminated from the Program, the action was found to be in error.[1] USDA did not attempt to calculate the amount of benefits that these improperly denied households would have received. As a result, this “negative error rate” is not directly comparable to the overpayment and underpayment error rates, but is instead a less rigorous measure of whether the state followed the proper procedures. Nonetheless, improper denials and terminations result in significant, if unintended, savings to the Program.

Although food stamp error rates have received little public attention in recent years, they do enter into discussions of the Program. Sometimes these discussions fall victim to significant mistakes or mischaracterizations of the food stamp error rates. To understand the error rates properly, several points should be kept in mind.

What the New Food Stamp Error Rates Show

- USDA actually issues three separate payment error rates: the overpayment error rate, the underpayment error rate, and the combined payment error rate. The overpayment error rate counts benefits issued to ineligible households as well as benefits issued to eligible households in excess of what federal rules provide. The underpayment error rate measures errors in which eligible, participating households received fewer benefits than the Program’s rules direct. The combined payment error rate is the result of summing (rather than netting) the overpayment and underpayment error rates.

Thus, for example, a state with a seven percent overpayment error rate and a two percent underpayment error rate would be reported as having a combined error rate of nine percent. The net loss to the federal government, however, from the errors in that state’s program (i.e., the benefits lost through overpayments minus those saved by underpayments) would be only five percent.[2]

As noted above, even this measure overstates the cost of errors to the Program. If it were possible to quantify the amount of benefits eligible households lost due to improper denials and terminations, the net loss to the program would be less. Indeed, it is possible that the combined savings from underpayments and improper denials is greater than the loss resulting from overpayments of benefits. The media often pay the most attention to the combined error rate, presenting it as a reflection of the dimension of excessive federal expenditures due to errors. This is incorrect since the combined error rate includes underpayments that save the Program money.

- For fiscal year 2002 USDA is imposing fiscal sanctions on states whose combined error rates exceeds the national average, even though overall state performance has improved for four consecutive years. This year, eight of the twenty states sanctioned improved their combined error rates from 2001 levels. An additional three of the states subject to sanction exceed the national average by less than one percentage point. Many of these states would not have been subject to sanction in other years when the national average happened to be higher. Delaware and Indiana, for example, are in sanction this year but would not have been last year with the same combined payment error rate.

- The decrease in error rates has been widespread. In 2002 ten states achieved their lowest combined payment error rates on record. Forty-two states have lower error rates in 2002 than they did in 1998 (a year when error rates peaked due in part to the complexity of implementing changes from the 1996 welfare law). Eleven of the 17 states that had combined payment error rates above the national average in 2001 improved their error rates in 2002.

- The dollar amount of most errors is quite small. A recent USDA study found that the overwhelming majority of food stamp overpayments went to eligible households and left the recipient households still well below the poverty line. It found that only two percent of recipient households are completely ineligible for food stamps and that only two percent of food stamp benefits are incorrectly issued to these ineligible households. In other words, 98 percent of food stamps are issued to eligible households. The study also found that the average overpayment raised the combined value of the household’s income and food stamps from 79 percent of the poverty line to 85 percent of the poverty line. (In 2003, 85 percent of poverty for a household of three is $1,064 a month or $12,800 a year.)

The Difference between Overpayments and Fraud

Relatively few of these errors represent dishonesty or fraud on the part of recipients (e.g., recipients intentionally lying to eligibility workers to get more food stamps). By its very nature, fraud is difficult to measure accurately. The overwhelming majority of food stamp errors, however, appear to result from honest mistakes by recipients, eligibility workers, data entry clerks, or computer programmers. In recent years, states have reported that half of all overpayments and two-thirds of underpayments were their fault. Most others resulted from innocent errors by households.[3] The Food Stamp Program has numerous anti-fraud measures in place, including sophisticated computer “matching” efforts to detect unreported earnings and assets, extensive requirements that households applying for or seeking to continue receiving food stamps prove their eligibility, and administrative and criminal enforcement mechanisms.

It also should be noted that an overpayment is counted in a state’s error rate whether or not the overpaid benefits are collected back from households. In fiscal year 2001, states collected over $200 million in overissued benefits. New collection techniques, such as intercepting wage earners’ income tax refunds, are expected to increase collections further.

In addition, the error rates measure the accuracy with which benefits are issued, not whether food stamps are redeemed or spent properly. Evidence from USDA research suggests that a very small fraction of food stamp benefits are improperly traded for cash, or “trafficked.” In 1998, USDA found that only three-and-a-half cents of every dollar issued in food stamps was trafficked. This has likely fallen to an even smaller proportion of benefits as the use of electronic benefit transfer (or EBT) — or providing food stamps on cards that can be swiped at stores like credit or debit cards — has expanded since 1998 to become virtually nationwide. One of the benefits of providing food stamp benefits through EBT is that it reduces the risks of trafficking by providing an electronic record of every transaction.

What Factors Contributed to States’ Error Rates

Although this latest release does not include information on the sources of errors, trends seen in prior years likely continued. A number of offsetting factors contribute to states’ error rates in recent years.

- The Economy. Since the beginning of the current economic downturn in March 2001, food stamp caseloads nationally have increased by 22 percent. Some of the states with the steepest increases in unemployment have also seen the largest increases in the number of people who receive food stamps. For example, food stamp caseloads have increased over the last two years by 48 percent in Oregon where the unemployment rate has increased significantly over the last two years to become among the highest in the country. This is a strong indication that the Food Stamp Program is working — that it is responding to increases in need as unemployment rises. These caseload increases are occurring, however, at the same time that states are facing very large budgets gap. Many are cutting back or freezing the number of eligibility workers who make food stamp eligibility determinations. (Although food stamp benefits are 100 percent federally-funded, states provide about half of the administrative costs for determining eligibility and issuing benefits.) The state budget crisis also can make it difficult for states to invest in computer upgrades, staff training, or other administrative activities that could help them improve their error rates.

In earlier recessions error rates have risen modestly when food stamp caseloads have increased. For example, between 1991 and 1993 when food stamp caseloads grew by 22 percent the combined payment error rate went from 9.3 percent to 10.31 percent. The fact that caseloads have been increasing and states have been under budget pressures makes the decline in error rates over the past few years even more remarkable.

- Increased share of working families receiving food stamps. Families’ movement from welfare to work also has tended to increase error rates. Households containing wage-earners historically have had higher error rates than those that rely solely on public assistance, SSI or Social Security. This is because many low-wage workers experience fluctuations in their earnings because of changing jobs or being asked to work a different number of hours week-to-week or month-to-month. If eligibility workers fail to adjust their benefit levels correctly each time, an over- or underpayment is likely to result. By contrast, welfare payments typically come in the same amount each month. (Moreover, since the state initiates any changes, it can plan for them in calculating recipients’ food stamp allotments.) Between 1990 and 2000 the proportion of food stamp households with children that work rose from a quarter to almost half, while the share of food stamp families with cash welfare and no earnings fell from almost 60 percent to 32 percent. The larger numbers of food stamp recipients that have been able to find work has likely increased in both the over- and underpayment error rates above the levels that would otherwise have prevailed. The fact that error rates are nonetheless declining means that improved state management and other factors have likely been in play to help offset this trend in the composition of food stamp households.

- Focus on cash assistance. In the late 1990s many states opted to concentrate their local offices’ staffs’ efforts on moving cash assistance recipients from welfare to work. —To allow their staffs to monitor closely the efforts of families being asked to move from welfare to work, many states substantially reduced the caseloads of those staff assigned to their TANF-funded programs. In some instances, this left eligibility workers responsible for food stamps with larger and less manageable caseloads.

- Changes in law or policy. In the late 1990s, a significant part of states’ overpayments resulted from states’ difficulties in implementing complex provisions of the 1996 welfare law, notably the provision denying food stamp eligibility to the majority of legal immigrants. On the other hand, changes that the Administration has made in policy and state options to simplify certain procedures in the delivery of food stamp benefits that were enacted in the 2002 farm bill — such as simplified rules regarding what changes in circumstances clients must report in between visits to the welfare office and options to streamline what counts toward the income and asset limits — have likely had a significant role in helping to reduce errors in recent years.

The Recent Changes to the Quality Control System

Prior to the 2002 reauthorization of the food stamp program, a consensus emerged among states, advocacy groups, USDA, and other policy makers that the food stamp QC system exerted an inappropriate influence on state policy. As noted, the prior system (which remained in effect for the 2002 error rates) subjected states with combined payment error rates above the national average to sanction. This set up half the states to be viewed as failures each year. As a result of this QC sanction system, states with high or rising error rates were under strong pressure from USDA to adopt policies that improve their error rates. State officials, governors, and state legislatures take these sanctions very seriously. Receiving a fiscal sanction can be perceived as a serious negative reflection on the state’s performance, even when the performance may be only modestly worse than average.

Some approaches that states may employ to reduce overpayments — improved staff training, giving eligibility workers more manageable caseloads, combating staff turnover, centralized change reporting functions, simplifying and better explaining households’ reporting obligations, etc. — also are likely to reduce underpayments and to improve needy families’ access to nutrition assistance. Other approaches, however, such as requiring working recipients to take time off work more frequently to come into the food stamp office for interviews, and increasing the amount of documentation a household must provide to verify their income and other circumstances, can have the effect of driving eligible families away from food stamps at the very time they may need these benefits to support their transition from welfare to work. This may have the effect of reducing states’ error rates by reducing participation by working poor families (a group with an above-average error rate). Unfortunately, it also undercuts efforts to make work more attractive than welfare and is likely to cause hardship for the families affected.

As a result of these concerns, the nutrition title of the 2002 farm bill included a major reform to the food stamp QC system’s sanction rules. While retaining the program’s strong commitment to payment accuracy, the new system will focus penalties on the few states with consistently high error rates. From a management perspective, this revised QC sanction system provides USDA with a broader range of options for how they respond to various payment accuracy concerns and how they assist states in improving their performance. USDA is now better equipped to provide different interventions for different types of states as opposed to having only the blunt legal requirement to sanction all states with measured error rates above the national average each year, regardless of the cause.

States that have chronic, long-term, excessive payment accuracy problems will still be subject to financial penalties and the new rules actually increase the likelihood that such states will pay fiscal penalties. However, many states experience short-term problems when, for example, they implement new computer systems, they implement a complex change in policy, or when their caseloads increase because of a downturn in the economy. In these states, it is counterproductive to take away resources at the very time that the state needs more resources to cope with the problem. Under the new system, states with short-term error rate problems will have time to work to correct the problems before they are faced with a fiscal penalty.

Specifically, a state will be subject to fiscal sanction if, with statistical certainty, its combined payment error rate exceeds 105 percent of the national average for two consecutive years. The new rules will go into effect beginning with the 2003 error rates, which will be released next summer. If the new rules had been in effect for 2002 error rates, instead of 20 states being subject to fiscal sanctions, only a handful of states would have received a fiscal penalty. In the future USDA will be able to focus energy on these states that have chronic problems. Another group of states — those that exceeded the threshold for the first year — would have been given notice that their error rates are high and that they are likely to be sanctioned the following year unless they take immediate corrective action. And every state with a combined payment error rate above six percent would be required to work with USDA to develop a corrective action plan to improve performance in future years.

The new QC system also includes new performance bonuses that reward exemplary achievements in payment accuracy and service to eligible households. Specifically, beginning in 2003, in addition awarding bonus funds to states that achieve low or improved error rates, USDA will also reward states with high or improved rates of serving eligible households and in doing so in a timely manner.

End Notes:

[1] For 2002 USDA did not release a national average for such “negative action” errors, but did publish them for each state. The approximation of a national average of eight percent is based on weighting the state error rates by the level of issuance of food stamp benefits in the state. While not precisely correct, this method closely approximates the national average in earlier years.

[2] To be sure, these savings are not sought or desired by either federal or state agencies. But in calculating the net cost to the federal government of errors, or the difference between the actual cost of the Program and what it would cost in the absence of errors, the value of benefits not provided due to underpayments must be subtracted.

[3] In fiscal year 2001, over 90 percent of all overpayments states established were classified as non-fraud. Some of these were innocent errors by households; others were mistakes the states themselves made.