THE RYAN-SUNUNU SOCIAL

SECURITY PLAN:

“Solving” the Long-Term Social Security Shortfall by

Raiding the Rest of the Budget

By

Robert Greenstein and Richard Kogan

| PDF of full report |

| If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

In 2003, Peter Ferrara, a conservative policy analyst and activist, proposed a plan to divert very large amounts of revenue from Social Security into private accounts and to restore long-term Social Security solvency without either benefit cuts or payroll tax increases. Ferrara’s plan was subsequently endorsed by Jack Kemp, Newt Gingrich, Grover Norquist, Steven Moore, and an array of conservative organizations. In 2004, Rep. Paul Ryan and Senator John Sununu introduced the plan, with minor changes.

The plan, which would shift substantially larger amounts from Social Security to private accounts than most other private-account plans, has been described by the Wall Street Journal editorial page as showing that “larger personal Social Security investment accounts can be financed without cutting benefits or raising taxes.” The plan has been touted by its proponents as a major breakthrough that shows Social Security can be converted to private accounts on a large scale, and long-term Social Security solvency restored at the same time, while guaranteeing that all current and future beneficiaries receive total benefits at least equal to those provided under the current benefit formula, and with no increases in payroll taxes. Indeed, the plan proposes to deliver all of these things and eventually to reduce payroll taxes as well. The plan is presented, in essence, as showing that its designers have found a way to provide a proverbial “free lunch.”

|

Ryan-Sununu Plan Would Cause Large Increases in Deficits, Debt, and Borrowing This analysis focuses on the large amount of general revenue transfers that the Ryan-Sununu plan would require. A related aspect of the plan is that it would sharply increase federal budget deficits, because very substantial amounts of federal revenue would be diverted from Social Security into private accounts, and that, in turn, would require the Treasury to borrow hefty sums in financial markets to finance the continued payment of Social Security benefits in the decades ahead. The Social Security actuaries found that under the Ryan-Sununu plan, the Treasury would have to borrow an additional $2.4 trillion (in current dollars) over the first ten years alone. The plan would increase the national debt (i.e., the debt held by the public) every year for at least the next 75 years. Increased deficits and debt would be avoided only if Congress made very deep cuts in other programs and/or if corporate income tax receipts boomed in an unprecedented manner that is extremely unlikely to occur. |

The plan also is presented by its supporters as having been certified as sound by the Social Security actuaries. The Wall Street Journal editorial page declared that it was “the conclusion of Steve Goss, the nonpartisan chief actuary of the Social Security Administration” that the Ferrara plan demonstrates that large amounts of Social Security funds can be directed to private accounts — and Social Security solvency can be restored — without cutting benefits or raising taxes.

Yet none of this is true. The plan’s finances rest entirely on the assumed transfer of extraordinary sums from the rest of the budget to Social Security, even though the budget outside of Social Security is in far worse financial shape today than Social Security is — and is projected to remain in much worse shape as far as the eye can see.

The Ryan-Sununu plan shifts enormous sums from the Social Security Trust Fund to private accounts and then backfills the Trust Fund with massive general revenue transfers from the U.S. Treasury (i.e., from the rest of the budget). The following data on the finances of the Ryan-Sununu plan come directly from the analysis of the plan issued by the Social Security actuaries. The actuaries found that:[1]

-

The plan would require general revenue transfers totaling $79 trillion over the next 75 years, measured in constant 2004 dollars.

- Economists generally prefer to express sums that cover long periods, such as 75 years, in “present value.” The actuaries reported that the assumed general revenue transfers would total $8.5 trillion in present value over the next 75 years.

- By way of comparison, the Social Security actuaries

reported that the entire Social Security shortfall over the next 75 years,

measured on a comparable basis, equaled $3.7 trillion in present value. In

other words, the Ryan-Sununu plan relies on general revenue transfers more

than twice as large as the entire Social Security shortfall. (As explained in

footnote 1, the actuaries’ estimates of the Ryan-Sununu plan are consistent

with the assumptions used for the 2004 trustees’ report, which showed a Social

Security shortfall of $3.7 trillion over 75 years, in present value. The 2005

trustees’ report shows a Social Security shortfall of $4.0 trillion.)

Economists also express such figures as a share of the economy. The general revenue transfers under the Ryan-Sununu plan over 75 years would total 1.5 percent of the Gross Domestic Product, the broadest measure of the economy. The Social Security actuaries project the size of the Social Security shortfall over this period to be 0.65 percent of the economy, or less than half the size of the transfers.

The Ryan-Sununu Plan and the Stock and Bond Markets

The Ryan-Sununu plan entails extraordinary amounts of additional investments in U.S. stock and bond markets. The Social Security actuaries’ figures show that by 2050, these additional investments would total 145 percent of GDP.

This means that by 2050, under the Ryan-Sununu plan, the entire U.S. market for stocks and corporate bonds would be held in the private accounts established under the plan. It is hard to imagine what would become of other private investors.

- Finally, the actuaries’ analyses indicate that if these massive general revenue transfers did not materialize, the Ryan-Sununu plan would greatly accelerate Social Security insolvency and make Social Security’s long-term actuarial imbalance much larger. Insolvency could come as early as 2020, rather than in 2042 as the actuaries project under current law, and the 75-year actuarial shortfall could increase by between 50 percent and 75 percent.[2]

Some proponents of the Ryan-Sununu plan seek to cloak these startling findings and to claim that the Social Security actuaries have certified the soundness of the plan and given it a “seal of approval.” This is decidedly not the case. The so-called “seal of approval” turns out to be nothing more than a finding on the part of the actuaries that if the massive general revenue transfers that the plan would mandate did occur, the plan would restore long-term Social Security solvency. This is hardly a breakthrough or an achievement of any sort. Any plan that requires general revenue transfers equal to more than twice the Social Security shortfall should be able on paper to restore long-term solvency to the program with room to spare.

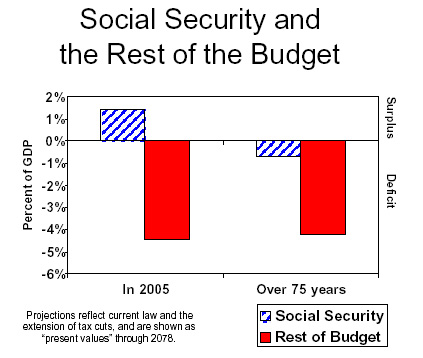

In essence, the Ryan-Sununu plan purports to solve the Social Security shortfall by shifting massive sums from the rest of the budget even though the rest of the budget has no money to spare. Indeed, as the graph on page 2 shows, Social Security is in good shape compared with the rest of the budget. Social Security is in surplus now, although it will be in deficit over the next 75 years and beyond. By contrast, the rest of the budget already suffers from an unsustainably large deficit and will continue to do so over the next 75 years, running deficits that dwarf Social Security’s.

|

White House Official Blasts Plans Such as Ryan-Sununu As Irresponsible (Without Naming the Plans) In a memo to fellow conservatives on January 5, 2005 that subsequently was leaked and widely reported, Peter Wehner, Director of Strategic Initiatives at the White House, took strong issue with the approach that the Ryan-Sununu plan embodies. Wehner wrote:

* Peter H. Wehner, Memo on Social Security, January 5, 2005, available at http://online.wsj.com/article/0,,SB110496995612018199,00.html |

In short, the Ryan-Sununu plan restores solvency through a gimmick — massive transfers from the rest of the budget. Private accounts themselves do nothing to restore solvency, as the President and the White House have acknowledged; only benefit cuts or revenue increases do that.

Given the sorry state of the federal budget outside Social Security, a truly notable accomplishment would have been to develop a plan that restores long-term Social Security solvency without any general revenue transfers. A recent book by M.I.T. economist and renowned retirement expert Peter Diamond and Brookings economist Peter Orszag does that.[3] The Diamond-Orszag plan demonstrates that it is possible to restore long-term solvency without transferring revenue from a budget already projected to be deep in deficit when the baby boomers retire, provided that one is willing to “bite the bullet” and include some benefit reductions, payroll tax increases, or a combination of the two.

Finally, the Ryan-Sununu plan also would increase the shortfall in the Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund and likely accelerate its insolvency. Under Ryan-Sununu, regular Social Security benefits would largely or entirely be replaced with proceeds from private accounts. (See box on page 7.) Currently, a portion of regular Social Security benefits is considered taxable income for better-off retirees, and the proceeds from the taxation of those benefits are dedicated to Medicare. Under Ryan-Sununu, by contrast, the proceeds of private accounts would be tax free even for retirees at high income levels. As a result, the plan’s replacement of much of Social Security with private accounts would cause Medicare to lose a significant source of revenue and make Medicare’s shortfall larger.

We now proceed to analyze the Ryan-Sununu plan in more detail.

How the Ryan-Sununu Plan Wishes Away the Social Security Shortfall

By counting on massive transfers from general revenues to Social Security, the Ryan-Sununu plan essentially wishes away the entire Social Security deficit. The actuaries’ analysis contains extensive information showing the magnitude of these general revenue transfers, and making clear that the plan falls apart without them.

The actuaries emphasize on page 1 of their analysis that under the Ryan-Sununu plan, “The ability of the Social Security Trust Funds to meet benefit obligations would be maintained through transfers from the General Fund of the Treasury that would be specified in the law.” Without these transfers, the plan would make Social Security’s deficit substantially larger, rather than smaller.

This can be seen by examining the analysis of the Ferrara plan that the actuaries issued in late 2003. The Ryan-Sununu plan is based on, and is extremely similar to, the Ferrara plan. (The actuaries calculated the effect of the Ferrara plan on the Social Security trust fund both with and without the assumed general-fund transfers; they calculated the effect of the Ryan-Sununu plan only with the assumed transfers.) The actuaries’ analysis of the Ferrara plan shows that under it, the Social Security trust fund would become insolvent in 2015 without the general funds transfers, long before the 2042 date of insolvency that the actuaries project under current law. Similarly, without the general-fund transfers, the actuarial imbalance in the Social Security trust fund over the next 75 years would made $1.8 trillion, or 50 percent, larger in present value than it currently is.[4]

The Magnitude of the Assumed General-Revenue Transfers

There are several ways of expressing the size of the assumed general-revenue transfers.

- Based on the actuaries’ estimates, we see that the Ryan-Sununu plan assumes $2.1 trillion in general revenue transfers over the ten-year period from fiscal year 2006 through fiscal year 2015 (measured in current dollars).[5]

|

Plan Poses an Additional Fiscal Threat Under the Ryan-Sununu plan, participants would receive a guarantee of benefits at least equal to those under the current Social Security benefit structure, regardless of the investment options they chose. The Social Security trust fund would act at a backstop to the private accounts: if an individual’s investments turned out badly, the government — i.e., the taxpayers — would make up the difference between what the private account actually earned and the amount needed to provide the individual the full level of benefits promised under the current Social Security benefit structure. This aspect of the Sununu-Ryan plan poses large additional risks for the rest of the budget. By insuring the holders of private accounts against bad investment results, the plan would encourage individuals to invest their private account balances in the riskiest allowable manner, hoping for the greatest returns. If the risky investments win big, the individual wins; if not, the rest of the budget (or the taxpayer) loses, not the individual investor. This would be a classic example of “moral hazard,” in which the presence of a third-party guarantee promotes irresponsible behavior on the part of individuals, with others — in the case, the taxpayers — left to bear all the risk. |

- Measured in constant 2004 dollars, the general revenue transfer would exceed $200 billion a year by 2015, surpass $300 billion a year by 2016, climb above $400 billion a year by 2020, and exceed $500 billion by 2024, including interest costs. The accumulated general revenue transfers from 2006 forward, expressed in 2004 dollars, would total $1.6 trillion by 2015, $3.4 trillion by 2020, and $79 trillion by 2078.

- For purposes of examining financial data over long periods of time, the

preferred practice is to measure a long-term cost in terms of its “present

value.” The “present value” of the assumed general revenue transfers is the

amount today that, with interest, would exactly cover the cumulative cost of

the general revenue transfers for the next 75 years.

Table 1a of the actuaries’ analysis presents the cost of the general revenue transfers in “present value” terms. It shows that over the next 75 years, the Ryan-Sununu plan assumes general revenue transfers from the rest of the budget that equal $8.5 trillion in present value. This assumed general-revenue transfer is more than twice the Social Security shortfall over the next 75 years, which the actuaries projected to be $3.7 trillion.[6] It should come as no surprise that the plan can eliminate the long-term deficit in Social Security: the plan simply assumes that the rest of the budget provides Social Security with resources equal to more than twice the entire deficit projected in Social Security over the next 75 years.

Assumed Financing for the General-Revenue Transfers

Given the magnitude of the plan’s general-revenue transfers, it is important to examine how they would be financed. The Ryan-Sununu plan assumes that the general revenue transfers would be financed in two ways: 1) by reducing the amounts budgeted for federal programs; and 2) by assuming that corporate tax revenues would increase substantially in the future. The plan’s authors contend that the plan would ignite more robust economic growth, which in turn would generate dramatic increases in corporate profits. The plan assumes that huge increases in corporate tax receipts would materialize and help finance the massive general revenue transfers.

As explained below, however, the budget cuts that the plan assumes are so large as to be implausible. Furthermore, despite the magnitude of the budget reductions that are assumed, the Ryan-Sununu plan fails to identify any specific cuts in any government programs that should be instituted to help generate the dramatic savings assumed to come from budget cuts. In addition, as also explained below, the extraordinarily rosy “dynamic scoring” assumptions that the Ryan-Sununu plan applies to corporate tax receipts are inconsistent with the established practices of the Congressional Budget Office, the Joint Committee on Taxation, the Office of Management and Budget, and the Treasury Department.

The Assumed Budget Reductions

When Mr. Ferrara first unveiled his plan, he sought to portray the reductions in government programs called for under the plan as being modest. They would require, he said, a reduction in the rate of budget growth of one percent per year for eight years. This presentation is misleading. For example, when Ferrara calculated the assumed budget cuts as a percentage of federal spending, he included Social Security in the federal spending base for purposes of calculating the spending reduction percentage. Since Social Security would not be cut, this made the percentage reduction in other programs look smaller than it actually would be.

|

Risks to Medicare The plan poses risks to the Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund. The HI Trust Fund currently is credited with part of the income taxes paid on Social Security benefits by high-income beneficiaries. The Ryan-Sununu plan would dramatically reduce or entirely eliminate traditional Social Security retirement benefits (see box on page 7). And all withdrawals from the private accounts, which would largely replace traditional Social Security benefits, would be tax free. The result would be to reduce revenue for the Medicare Hospital Insurance program, which already faces an insolvency problem of its own. Under current law, by 2050 more than 13 percent of Medicare Hospital Insurance revenues would come from the taxation of Social Security benefits, much of which would be lost under the plan. The plan consequently would accelerate the point at which the Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund would become insolvent and would increase the unfunded liability that the Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund faces. |

Moreover, Social Security, Medicare, defense and homeland security, and interest payments on the debt account for the vast majority of federal spending. Social Security would, as noted, be off limits for reductions under the plan, and reductions in interest payments on the debt cannot be legislated. In addition, in recent years, policymakers have expanded the budgets for Medicare, defense, and homeland security, not reduced them

It therefore is instructive to examine the size of the assumed budget cuts relative to total federal expenditures for non-defense discretionary programs (outside of homeland security). In 2015, the Ryan-Sununu plan assumes that government spending can be reduced by $284 billion (in current dollars). Under CBO projections, non-defense discretionary spending outside homeland security is expected to equal $535 billion that year. Thus, given the unlikelihood of cuts in defense, homeland security, Medicare, and other entitlements such as veterans programs, the Ryan-Sununu plan can be seen as assuming we can eliminate more than half of all non-defense discretionary spending outside homeland security. That part of the budget includes education, law enforcement, infrastructure, biomedical research, environmental protection, tax collecting, and national parks and other natural resources. An assumption of such severe reductions in this part of the budget is not credible.

Nor is credibility enhanced by assuming that every program except Social Security would be subject to cuts. If all programs except Social Security were cut, the reductions would reach 11 percent of program costs by 2015, and would affect Medicare, military retirement and health benefits, national defense, veterans' disability compensation, veterans' health care, homeland security, and other anti-terrorism spending abroad, among others.

Furthermore, these unrealistically large assumed cuts in government programs would have to be even larger if the private accounts did not perform as projected. Under the Ryan-Sununu plan, the federal government would guarantee that individuals would receive, from the combination of their private accounts and Social Security benefit payments, an amount at least equal to the full benefit that the current Social Security benefit formula would provide. This guarantee would hold regardless of how risky an investment strategy an individual pursued with his or her private account. Thus, if the stock market did not perform as well as assumed, the required transfers to Social Security from the rest of the budget would have to be even larger than the already massive transfers that this analysis describes. These even larger transfers would have to be made regardless of whether Congress found a way to finance them. The increased transfers would be financed by an even greater amount of borrowing.

In short, a key aspect of the Sununu-Ryan plan is that it would essentially pledge to restore long-term Social Security solvency by promising to borrow whatever was needed to keep paying benefits.

It may be noted that this is a hollow way to “guarantee” future Social Security benefits. Congress could act tomorrow to guarantee all promised benefits in perpetuity simply by enacting a legal promise to borrow money as needed to pay the benefits. Doing so would, of course, fail to address the question of how the budget or the nation could afford such unlimited borrowing.

The Assumed Corporate Tax Revenue

The Ryan-Sununu plan also assumes that its private accounts would generate huge increases in corporate income tax receipts.

Corporate income tax receipts would be much higher, Ryan and Sununu contend, because their plan would greatly boost national saving, which, in turn, would ignite investment and cause a permanent surge in corporate profits. But merely shifting payroll tax revenue from Social Security into private accounts does not boost national saving at all. The large spending cuts that the Ryan-Sununu plan envisions could increase national saving, but those massive cuts are unlikely to occur. If these large program cuts do not materialize, the private accounts would be deficit financed, with the result that national saving would not rise. (Under the plan, the private accounts must be established — and the general revenue transfers must be made — regardless of whether the program reductions and the assumed corporate revenue increases actually materialize. If they do not materialize, the required diversion of federal revenue into private accounts would directly increase the federal deficit.)

In short, it is far from clear that national saving would increase at all under the plan, let alone increase by the massive amounts the proposal’s authors assume. Without the increase in national saving, none of the assumed increase in corporate income tax receipts would occur.

Even if some increase in national saving did occur, the scale of the increases in national saving and corporate tax receipts that the Ryan-Sununu plan assumes is not plausible. The plan assumes that corporate income taxes will increase by an amount equal to 3.3 percent of GDP by 2078. By comparison, total corporate income tax collections averaged only 1.9 percent of GDP during the 1990s and 1.6 percent of GDP in 2004. In addition, recent CBO budget projections show corporate tax receipts at a steady 1.5 percent of GDP from 2011 through 2015. In other words, the plan blithely assumes that corporate tax revenue will more than triple relative to GDP as a consequence of the plan. Such a grandiose assumption cannot be taken seriously.

General Revenue Transfers Not Contingent on Offsetting Savings

As we have seen, the financing for the massive general revenue transfers that the plan assumes is very unlikely to materialize in anything close to the assumed amounts, if the financing materializes at all. The Office of the Chief Actuary of the Social Security Administration did not evaluate the plausibility of the plan’s assumptions in this area, since the general revenue transfers would be required by law and would not be contingent on either government spending declining or corporate income tax revenue rising. As the actuaries’ memorandum emphasizes, “Specified transfers to the Trust Funds would, however, not be contingent on achieving these reductions in actual Federal spending.” In other words, the assumed transfers to Social Security would occur regardless of whether the implausible mechanisms for financing the transfers actually worked. This underscores the fiscal recklessness of the plan.

The bottom line is that, despite claims by the plan’s supporters to have shown that Social Security solvency can be restored without any benefit reductions or payroll tax increases, all that the Ryan-Sununu plan actually shows is that if one makes general-revenue transfers equal to more than twice the entire Social Security shortfall, long-term Social Security solvency can be restored on paper (and large private accounts created) without benefit cuts or payroll tax increases. The general revenue transfers merely shift the burden of financing the Social Security shortfall from the trust fund to the general fund, without in any way reducing that shortfall. And the Ryan-Sununu plan simply assumes that the general fund will be able to handle this increased burden. It bears repeating that the Office of the Chief Actuary did not embrace or approve these assumptions; it merely calculated the effect of the Ryan-Sununu plan on Social Security, given the assumptions made by the plan’s authors. Requiring general revenue transfers more than twice the size of the entire Social Security deficit over the next 75 years does not represent a meaningful or responsible reform plan.

End Notes:

[1] Steve Goss, “Estimated Financial Effects of the ‘Social Security Personal Savings and Prosperity Act of 2005,’”April 20, 2005. The Goss memorandum applies to S. 857 (Sununu) and H.R. 1776 (Ryan). All figures in our analysis are taken directly from this memorandum, are calculated from data in the memorandum, or are calculated from data in the memorandum combined with data from Social Security Administration, “2004 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Trust Funds,” March 17, 2004, available at http://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TR/TR04/tr04.pdf, and supporting tables available at http://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TR/TR04/lrIndex.html. The actuaries’ calculations of the effects of the Ryan-Sununu plan are consistent with the assumptions in the 2004 Trustees’ Report.

[2] The 2042 insolvency date is from the trustees’ 2004 report, which is the basis for the actuaries’ estimates of the Ryan-Sununu plan. The 2005 trustees’ report shows an insolvency date of 2041.

[3] Diamond, Peter A. and Peter R. Orszag, “Saving Social Security: A Balanced Approach,” Brookings Institution Press, 2003.

[4] For the actuaries’ analysis of the Ferrara plan, see Steve Goss, “Estimated Financial Effects of the “Progressive Personal Account Plan,’” December 8, 2003. The Ryan/Sununu plan produces financial results very similar to those of the Ferrara plan. The Ryan-Sununu plan relies on general-fund transfers similar to, but larger than, those called for under the Ferrara plan. The actuaries’ analyses show that the Ferrara plan includes general-fund transfers totaling $68.3 trillion over 75 years in constant 2003 dollars; their analyses show that the general fund transfers under the Ryan-Sununu plan would total $79.3 trillion in 2004 dollars.

[5] The Goss memorandum on the Ryan-Sununu plan, op cit, portrayed general revenue transfers in constant 2004 dollars, e.g., in Table1a of that memorandum. We have converted constant to current dollars using the conversion factors in the supporting tables accompanying the 2004 Trustees’ Report (see note 1). Our figures include both the direct amount of the specified transfers from the general fund and the interest that the general fund pays to Social Security on these transferred amounts.

[6] The $8.5 trillion estimate of the 75-year present-value cost of the general fund transfers to Social Security appears in Table 1a of Goss, op. cit. The Goss memorandum is based on the economic and other estimating assumptions used by the Social Security Trustees in their 2004 report. The $3.7 trillion present-value estimate of the 75-year Social Security shortfall is from the 2004 Trustees’ Report (Table IV.B7) rather than from the 2005 report, for comparability. (The equivalent estimate from the 2005 Trustees’ report is $4.0 trillion.) The Goss memorandum on the Ryan-Sununu plan states that updating the analysis to reflect 2005 estimating assumptions would produce estimates that are “not expected to be materially different from those provided in this memorandum.” Goss, page 2.