|

Revised July 27, 2006

CLAIM THAT TAX CUTS “PAY FOR THEMSELVES” IS TOO GOOD TO BE TRUE:

Data Show No “Free Lunch” Here

by Richard Kogan and Aviva Aron-Dine

In recent statements, the President, the Vice President, and key Congressional leaders have asserted that the increase in revenues in 2005 and the increase now projected for 2006 prove that tax cuts “pay for themselves.” In other words, the economy expands so much as a result of tax cuts that it produces the same level of revenue as it would have without the tax cuts.

President Bush, for example, commented on July 11, “Some in Washington say we had to choose between cutting taxes and cutting the deficit…. that was a false choice. The economic growth fueled by tax relief has helped send our tax revenues soaring.”[1] Earlier, in a February speech the President stated, “You cut taxes and the tax revenues increase.”[2] Similarly, Vice President Cheney has claimed, “it’s time for everyone to admit that sensible tax cuts increase economic growth and add to the federal treasury.” [3] And Majority Leader Frist has written that recent experience demonstrates, “when done right, [tax cuts] actually result in more money for government.”[4]

In fact, however, the evidence tells a very different story: the tax cuts have not paid for themselves, and economic growth and revenue growth over the course of the recovery have not been particularly strong.

-

Even taking into account the stronger revenue growth now projected for fiscal year 2006, real per-capita revenues have simply returned to the level they reached more than five years ago, when the current business cycle began in March 2001. (March 2001 was the peak and thus the end of the previous business cycle, and hence also the start of the current business cycle.) In contrast, in previous post-World War II business cycles, real per-capita revenues have grown an average of about 10 percent over the five and a half years following the previous business-cycle peak.[5] By this stage in the 1990s business cycle, real per-capita revenues had increased by 11 percent.

-

Overall, this economic recovery has been slightly weaker than the average post-World War II recovery. In particular, GDP growth and investment growth have been below the historical average, despite recent tax cuts specifically targeted at increasing investment.

Those who claim that tax cuts pay for themselves might argue that stronger revenue growth in 2005 and 2006 represents the beginning of a new trend, and that the tax cuts could pay for themselves over the longer term. Neither the historical record nor current revenue projections support this argument.

-

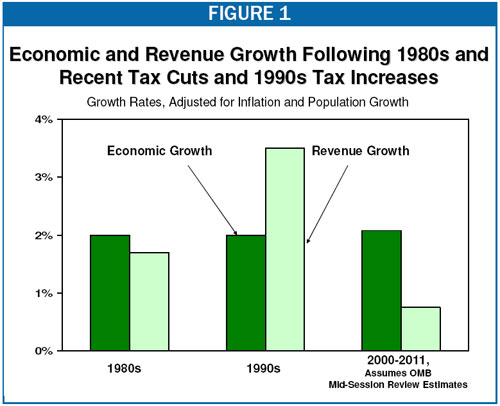

In 1981, Congress approved very large supply-side tax cuts, dramatically lowering marginal income-tax rates. In 1990 and 1993, by contrast, Congress raised marginal income-tax rates on the well off. Despite the very different tax policies followed during these two decades, there was virtually no difference in real per-person economic growth in the 1980s and 1990s. Real per-person revenues, however, grew about twice as quickly in the 1990s, when taxes were increased, as in the 1980s, when taxes were cut. (See Figure 1.)

-

Even the Administration does not project that revenues will continue to grow at their recent rates or that the tax cuts will pay for themselves. Under the revenue assumptions in the Office of Management and Budget’s Mid-Session Review, real per-person revenues will grow at an annual average rate of just 0.8 percent between 2000 and 2011, only about half the growth rate during the 1980s and less than one-fourth the growth rate during the 1990s.

-

Studies by the Congressional Budget Office, the Joint Committee on Taxation, and the Administration itself show that tax cuts do not come anywhere close to paying for themselves over the long term. CBO

and Joint Tax Committee studies find that, if financed by government borrowing,

tax cuts are more likely to harm than to help the economy over the long run, and

consequently would cost more than conventional estimates indicate, rather than

less. Moreover, in its recent “dynamic analysis” of the impact of making

the President’s tax cuts permanent, the Treasury Department reported that even

under favorable assumptions, extending the tax cuts would have only a small effect on economic output. That small positive economic impact would offset no more than 10 percent of the tax cuts’ cost. (See box on page four.)

In addition, economists from across the political spectrum — including economists who have held top positions in the current Administration — reject the argument that tax cuts pay for themselves (see the discussion of this issue on page five). In tax policy, as in other aspects of policymaking, there is no “free lunch.”

Have the Tax Cuts Increased Revenues?

After adjusting for inflation and population growth, this year and last year’s strong growth in revenues have barely made up for the deep revenue losses in 2001, 2002, and 2003. Measured since the current business cycle began in March 2001, total per-capita revenue growth, adjusted for inflation, has been near zero. Based on OMB’s latest revenue estimates, real per-capita revenues in 2006 will be only 0.2 percent above the level they attained more than five years ago at the start of the business cycle. In other words, the current revenue “surge” is merely restoring revenues to where they were half a decade ago.

By contrast, five and a half years after the peak of previous post-World War II business cycles, real per-capita revenues had increased by an average of 10 percent. And at this point in the 1990s business cycle, real per-capita revenues were 11 percent higher than their level at the end of the previous business cycle.[6]

Furthermore, the performance of the economy during the current business cycle has been slightly weaker overall than the economy’s average performance over the comparable period of other business cycles since the end of World War II. Investment growth during the current business cycle has been below the historical average, even though some of the Bush administration’s tax cuts have been specifically targeted at investment. Employment and wage and salary growth have been especially weak during the current business cycle.[7] If tax cuts are crucial to economic growth, then the current business cycle — with its large tax cuts — should strongly outperform previous business cycles. Instead, it has performed more poorly than average.

|

Treasury

Department Study Finds the Bush Tax Cuts Will Pay For Less Than 10 Percent of Their Cost

According to CBO’s official cost estimate, the Administration’s proposal to make

the tax cuts enacted since 2001 permanent would cost 1.4 percent of GDP

annually. (This does not include the AMT relief that the Administration

proposes on an annual basis, which would bring the total cost to 2 percent of

GDP.)

According to the Mid-Session Review, the tax cuts would have positive long-term

economic effects that would raise national income by “as much as” 0.7 percent

over the long term. With tax receipts projected to be about 18 percent of

national income, this translates into an increase in revenues of as much as 0.13

percent of GDP.a In this scenario, which assumes that the tax cuts are financed

by future cuts in government spending, the tax cuts would cost about 1.27

percent of GDP annually — or more than 90 percent of the conventional

cost estimate. (Under Treasury’s alternative financing scenario, the tax cuts

would actually reduce national income over the long run.) |

Could the Tax Cuts Pay for Themselves Over Time?

Proponents of the tax cuts might argue that the stronger revenue growth in 2005 represents the beginning of a trend and that the tax cuts will pay for themselves over time. This claim is contradicted by the historical record, as well as by the Administration’s own projections.

Tax Cuts Have Not Paid for Themselves in the Past

Senator Charles Grassley (R- IA) recently stated, “There is a mindset in both branches of government that if you reduce taxes you have a net loss, if you increase taxes you have a net gain, and history does not show that relationship.”[8] A look at the past two decades, however, shows exactly that relationship.

In 1981, Congress substantially lowered marginal income-tax rates on the well off. In 1990 and 1993, by contrast, Congress raised marginal income-tax rates on the well off. When the 1981 tax cuts were being debated, some supporters contended the tax cuts would more than pay for themselves. Similarly, opponents of the 1990 and 1993 tax increases claimed they would damage the economy and cause tax receipts to grow more slowly in the 1990s than in the 1980s.

In fact, the economy grew at about the same rate in the 1990s as in the 1980s, while tax revenues grew about twice as fast in the 1990s as in the 1980s: 3.5 percent (after adjustment for inflation and the increase in the size of the population), compared to 1.7 percent in the 1980s.

The Administration Itself Does Not Project that the Tax Cuts Will Pay for Themselves

The revenue estimates in OMB’s Mid-Session Review show that even the Administration does not expect the tax cuts to produce revenue growth that would make up for their costs. Based on the Mid-Session Review projections for revenues in 2006-2011, real per-person revenues will grow at an annual average rate of 0.8 percent between 2000 and 2011, only about half the growth rate during the 1980s and less than one-fourth the growth rate during the 1990s.

|

Table 1:

Economic and Revenue Growth Rates

in the 1980s and 1990s |

|

|

Average Economic Growth[9] |

Average Revenue Growth |

|

1980s[10] |

2.0% |

|

1.7% |

|

|

1990s |

2.0% |

|

3.5% |

|

|

2000-2011,

(Based on OMB’s Mid-Session Review Estimates) |

2.1% |

|

0.8%

|

|

These results are especially striking given that the Administration’s revenue estimates are highly inflated in one key respect — they assume that relief from the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) will not be extended beyond 2006, with the result that 30 million households will pay the AMT by 2010. Virtually all observers expect AMT relief to be continued. If the Administration’s revenue estimates are adjusted by using CBO’s estimates of the cost of continuing AMT relief, the estimates then show real per-capita revenue growth over the 2000-2011 period averaging only 0.5 percent per year.

In addition, the Treasury Department’s own recent “dynamic analysis” of the effects of making the President’s tax cuts permanent shows that the tax cuts would not come anywhere close to paying for themselves.

In the Treasury study's more optimistic scenario, extending the tax cuts could eventually increase long-run economic output by a total of 0.7 percent of GDP, which is enough to pay for, at most, 10 percent of the tax cuts’ cost.[11]

Economists Across the Political Spectrum Reject Claims that Tax Cuts Pay for Themselves

While serious economists are divided on the question of whether and under what circumstances tax cuts are good for the economy, there is no such debate on the question of whether tax cuts pay for themselves. Economists from across the political spectrum reject the latter assertion.

In recent testimony before Congress’s Joint Economic Committee, Edward Lazear, current chairman of President Bush’s Council of Economic Advisors, stated, “I certainly would not claim that tax cuts pay for themselves.”[12]

|

Are Capital Gains Tax Cuts Different?

In its most recent Budget and Economic Outlook report issued in late January, 2006, CBO revised upward its estimates of capital-gains revenues over the 2003-2005 period. Some have cited this CBO reestimate as evidence that capital-gains tax cuts, if not other tax cuts, pay for themselves. More careful scrutiny shows, however, that this narrower claim is seriously flawed as well.

-

CBO noted that it has raised its estimate of capital-gains revenues based on information showing higher-than-expected capital-gains realizations. Describing this reestimate as a “technical revision,” CBO explained that capital-gains realizations have been above historical levels (relative to GDP and the capital-gains tax rate) over the past few years, but that it does not expect this trend to continue. The effect of the lower capital gains tax rates on CBO’s reestimates of capital-gains realizations was minor.

-

The higher capital-gains realizations do reflect, in part, the rise in the stock market in 2003, which rebounded after three consecutive down years. Capital-gains realizations and revenues tend to go up and down with the market. But a recent study by three Federal Reserve economists demonstrates that the capital-gains and dividend tax cuts of 2003 were not the reason that the market went up that year.a

|

N. Gregory Mankiw, former chairman of President Bush’s Council of Economic Advisors and a Harvard economics professor, wrote in his well-known 1998 textbook that there is “no credible evidence” that “tax revenues … rise in the face of lower tax rates.” He went on to compare an economist who says that tax cuts can pay for themselves to a “snake oil salesman trying to sell a miracle cure.”[13]

Commenting on President Bush’s claim that tax cuts pay for themselves, the Economist magazine recently wrote, “Even by the standards of political boosterism, this is extraordinary. No serious economist believes Mr. Bush’s tax cuts will pay for themselves.”[14]

The President’s own Council of Economic Advisors concluded in its Economic Report of the President, 2003, that, “although the economy grows in response to tax reductions (because of the higher consumption in the short run and improved incentives in the long run) it is unlikely to grow so much that lost revenue is completely recovered by the higher level of economic activity.”[15] The CEA chair at the time was conservative economist Glenn Hubbard.

Deficit-Financed Tax Cuts May Cost Even More than Official Estimates

A recent CBO study of the economic effects of tax cuts found that how tax cuts are financed significantly impacts how they affect the economy. In the short run, deficit-financed tax cuts may help stimulate an economy in recession and thus temporarily improve growth (although the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts were poorly structured as stimulus). But in the long run, the deficits that result from unpaid-for tax cuts constitute a drag on the economy because they lower national savings.[16]

For this reason, deficit-financed tax cuts may actually weaken long-run economic growth. A study and literature review by Brookings Institution economists William Gale and Peter Orszag, for instance, concluded that the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts were “likely to reduce, not increase, national income in the long term” because of their effect in swelling the deficit.[17] Studies by economists at the Congressional Budget Office and the Joint Committee on Taxation have found that, even in models that predict that deficit-financed tax cuts can have a positive economic impact over the ten-year budget window, their longer-run impact is negative.[18]

If deficit-financed tax cuts weaken economic growth, their long-run cost could be greater than conventional revenue estimates suggest, because they will reduce revenues not only directly (by lowering people’s tax bills) but also indirectly (by slowing the economy). A recent CBO study of the economic effects of a hypothetical 10 percent across-the-board cut in income tax rates found that under certain assumptions, the increased deficits resulting from the tax cut would be enough of a drag on the economy that the tax cut actually would lose more revenue than if one assumed it had no effect on the economy. In other words, deficit-financed tax cuts could be even more expensive than officially “scored,” rather than less expensive or costless.

In the final analysis, the idea that tax cuts can spur sufficient economic growth to pay for themselves sounds too good to be true because it is too good to be true. In tax policy, as in other aspects of policymaking, there is no “free lunch.”

End Notes:

[1] “Remarks by the President on the Mid-Session Review,” July 11, 2006.

[2] “President Discusses 2007 Budget and Deficit Reduction in New Hampshire,” February 8, 2006.

[3] “Remarks by the Vice President on the 2006 Agenda,” Washington D.C., February 9, 2006.

[4] Bill Frist, “Tax Cuts Make Money,” USA Today, February 21, 2006.

[5] We consider here the revenue growth that the Administration projects through the end of fiscal year 2006. The fiscal year will end on September 30, 2006, which will be 5 ½ years after the business cycle began in March 2001. Hence, the equivalent period of earlier business cycles is the first 5 ½ years of those cycles.

[6] Aviva Aron-Dine, Joel Friedman, Richard Kogan, and Isaac Shapiro,

“The Recent Upturn in Revenues and OMB’s Mid-Session Review,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised July 11, 2006.

[7] For more detailed comparisons, see Isaac Shapiro, Richard Kogan, and Aviva Aron-Dine, “How Good Is the Current Economic Recovery?” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised July 10, 2006.

[8] Wesley Elmore, “Snow Touts Dynamic Analysis before Ways and Means Committee,” Tax Notes, February 16, 2006.

[9] Growth rates are adjusted for inflation and population growth.

[10] Growth rates are measured from business cycle peak to business cycle peak (fiscal years 1979 to 1990 and fiscal years 1990 to 2000). By measuring growth over complete business cycles, we avoid the distortions that could result from, for example, comparing an expansion to a recession.

[11] James Horney, “A Smoking Gun: Claim that Tax Cuts Pay for Themselves Refuted by Administration’s Own Analysis,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities,

revised July 27, 2006.

[12] Edward Lazere, Testimony before the Joint Economic Committee, June 27, 2006.

[13] N. Gregory Mankiw, Principles of Economics, Dryden Press, Fort Worth, TX, 1998, pp. 29-30.

[14] The Economist, “Tripe Is Back on the Menu,” January 14, 2006.

[15] Council of Economic Advisors, Economic Report of the President, February 2003, pp. 57-58.

[16] Congressional Budget Office, “Analyzing the Economic and budgetary Effects of a 10 Percent Cut in Income Tax Rates,” December 1, 2005. See also Isaac Shapiro and Joel Friedman, “Tax Returns: A Comprehensive Assessment of the Bush Administration’s Record on Cutting Taxes,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised April 23, 2004, chapter 4, https://www.cbpp.org/4-23-04tax.pdf

[17] Williams Gale and Peter Orszag, “Bush Administration Tax Policy: Effects on Long-Term Growth,” Tax Notes, October 18, 2004.

[18] Douglas Hamilton, “Dynamic Analysis of a 10 Percent Cut in Federal Income Tax Rates,” June 16, 2006, Joint Committee on Taxation, “Exploring Issues in the Development of Macroeconomic Models for Use in Tax Policy Analysis,” June 16, 2006. |