INCOME TAX RATES AND HIGH-INCOME TAXPAYERS:

How Strong Is The Case For Major Rate Reductions?

SUMMARY

by Isaac Shapiro and Joel Friedman

| View PDF of full report View PDF of this summary HTML of factsheet PDF of factsheet If you cannot access the file through the link, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

Should it be a national priority to lower marginal tax rates substantially in all tax brackets, including the higher brackets? Those who support large tax-rate reductions in the upper brackets emphasize that the share of federal taxes those in the top brackets pay has increased significantly in recent years. They also argue that as a result of increases in top marginal rates enacted in 1990 and 1993, these rates have grown so high that individuals in these brackets are discouraged from risk-taking and work effort. Both the amount of taxes that upper-income families pay and the marginal tax rates they face have been depicted as being sufficiently high as to be unduly burdensome, unfair, and injurious to the economy.

This analysis seeks to examine these issues. It relies primarily on the latest data available from the Internal Revenue Service on income and income tax trends. For some of this information, the latest IRS data are for 1997; for other information, the latest IRS data are for 1998. These IRS data break out taxpayers by the highest marginal tax rate they pay. The data also break out income and income tax trends for various groups — such as the top one percent of taxpayers — on an annual basis. The trends the IRS data depict are consistent with the trends reflected in estimates the Congressional Budget Office and the Joint Committee on Taxation have issued during the past two months.

The key findings of this analysis are summarized here.

Current Marginal Tax Rates and the Administration's Proposal

| In 1997, only four percent of filers were in the 31 percent bracket or a higher bracket, and fewer than one percent were in the top bracket. |

The tax code currently contains five income tax brackets, with marginal tax rates ranging from 15 percent to 39.6 percent. The marginal tax rate is the rate that applies to each additional dollar of taxable income.

Only a very small share of tax filers have incomes high enough to be subject to the highest marginal income tax rates. IRS data show that in 1997, the latest year for which this information is available:

- Less than one-quarter of all tax filers were in tax brackets higher than the 15 percent bracket.

- Only four percent of tax filers were in the 31 percent bracket or a higher bracket.

- Less than one percent of filers were in the top bracket, where the marginal tax rate is 39.6 percent. The average adjusted gross income of filers in the 39.6 percent bracket exceeded $900,000 in 1997.

Since 1997, the proportions of families that have high incomes and thus are in the higher tax brackets have increased somewhat. Even so, with only four percent of tax filers facing marginal rates of 31 percent or above in 1997, the fraction of tax filers subject to the top rates remains small today.

The part of the Administration's tax proposal the House of Representatives passed on March 8 includes a provision to reduce the higher marginal rates (i.e., the rates above 15 percent). These rate reductions would have no effect on the bottom three-quarters of tax filers. Nevertheless, this provision is the costliest part of the President's overall tax package; the rate reductions make up 30 percent of the cost of the Bush package, when it is phased in fully.

| The percentage of income paid in federal income taxes remains below 20 percent even for most higher-income taxpayers. |

The Bush tax proposal and the House-passed bill (H.R. 3) also would create a new 10 percent tax bracket. This new bracket would benefit upper-income as well as middle-income taxpayers, since part of the taxable income of all such taxpayers would be taxed at the 10 percent rate.

Most low- and many moderate-income families would not be affected by any of these proposals because they do not owe federal income taxes. Many of these families pay significant amounts of other taxes.

Recent Tax Trends

The maximum marginal income tax rates that those at the top of the income spectrum pay are higher now than the marginal rates such individuals faced in the late 1980s. The current top rates are, however, much lower than the top marginal rates during the 1960s and 1970s.

A family's marginal income tax rate — the rate it pays on the last dollar of income it earns — differs from its effective income tax rate. A family's effective income tax rate is the percentage of its overall income that it pays in income taxes. Effective tax rates are much lower than marginal rates and have increased to a much lesser degree over the past decade. Average effective tax rates (referred to hereafter simply as "average tax rates") remain below 20 percent even for most higher-income taxpayers. Average rates fell significantly between 1996 and 1998, the latest year for which these data are available.

For upper-income families, some income is not taxed at all due to deductions and exemptions available to all taxpayers, while some income is taxed at the 15 percent marginal rate, some is taxed at the 28 percent marginal rate, some is taxed at higher rates, and some is taxed at the capital gains tax rate of 20 percent. As a result, the average income tax rates that high-income families face are sharply lower than their marginal tax rates.

- The IRS data show that in 1997, filers in the 28-percent tax bracket faced an average income tax rate of only 14.3 percent. The average income tax rate that filers in the 31-percent bracket faced was 19.5 percent.

- Only those in the 36 percent and 39.6 percent brackets — a group that includes fewer than two percent of all filers — paid more than 20 percent of their income in federal income taxes.

| Highest Marginal Rate | Average Income Tax Rate | Percent of Tax Filers |

| 28% | 14.3% | 19.6% |

| 31% | 19.5% | 2.4% |

| 36% | 23.2% | 1.0% |

| 39.6% | 29.9% | 0.6% |

| Source: CBPP calculations based on IRS data. | ||

- Even among the small number of families in the 39.6 percent marginal bracket — a group that includes fewer than one percent of all tax filers — the average income tax rate in 1997 was 30 percent, or less than one-third of their income. Indeed, the only Americans who pay more than one-third of their income in federal income taxes are a tiny group of extremely high-income individuals who make up a small fraction of one percent of all filers and who earn enormous amounts.

Recent Declines in Average Tax Rates

for High-income Filers

In the past few years, the average income tax rate that the top one percent of tax filers pay has declined, falling from 28.9 percent in 1996 to 27.1 percent in 1998. This drop occurred primarily because of a large increase in capital gains income, which is taxed at a lower rate than other income and is heavily concentrated among those at the top of the income scale. The reduction in the top long-term capital gains tax rate from 28 percent to 20 percent enacted in 1997 also contributed to this decline in average income tax rates among high-income filers.

It may be noted that the Joint Committee on Taxation estimates the top one percent of taxpayers will face a somewhat lower average income tax rate — 25.7 percent — in 2001. The Committee's estimate may be lower than the IRS estimate at least in part because of a continued decline in average tax rates between 1998 and 2001, although inconsistencies between the two sets of data make this difficult to assess. It is clear, however, that the IRS data modestly overstate the share of income that taxpayers pay in taxes because the IRS data use a narrower measure of income. (The IRS income measure, for instance, does not include tax-exempt interest or the portion of pension benefits that is not taxable. The Joint Tax Committee data include these income sources.)

| In the past few years, the percentage of income the top one percent of tax filers pays in income tax has declined, falling from 28.9 percent in 1996 to 27.1 percent in 1998. |

These figures suggest that focusing solely on the marginal tax rates that high-income taxpayers face while ignoring their much-lower average tax rates may lead to an exaggerated sense of the tax burdens that high-income taxpayers face. For example, the President, in his speech before a Joint Session of Congress on February 27, 2001, stated that "No one should pay more than a third of the money they earn in federal income taxes." IRS and Joint Tax Committee data show that even the top one percent of families currently pay significantly less than one-third of their income in federal income taxes; on average, they pay a little more than one-quarter of their income in federal income taxes.

Recent Income Trends

| The primary force behind the increase in the share of income taxes those at the top of the income spectrum pay has not been increases in tax rates; it has been a dramatic rise in the before-tax incomes of these high-income individuals, which has far outstripped increases in income for other Americans. |

The share of income taxes that the top one percent of filers pay has increased substantially since the end of the 1980s. This is a point that proponents of lowering the top tax rates often cite. In 1989, the top one percent of filers paid 25.2 percent of federal income taxes, according to the IRS data. In 1998, they paid 34.8 percent. (The top one percent pay a much larger share of the progressive income tax than of all federal taxes; the top one percent pay 24 percent of all federal taxes.)

The primary driving force behind the increase in the share of income taxes that those at the top of the income spectrum pay has not, however, been increases in tax rates. The primary factor has been a dramatic increase in the before-tax incomes of these high-income individual, an increase that has far outstripped increases in income for other Americans. Approximately two-thirds of the increase in the share of income taxes paid by the top one percent of tax filers that occurred between 1989 and 1998 reflected the increased concentration of income at the top of the income scale rather than higher tax rates.(1)

Both Before- and After-Tax Income Gains Substantial for Top One Percent

The IRS data provide information through 1998 on the incomes of the top one percent of tax filers, a group primarily made up of filers that face a marginal income tax rate of either 36 percent or 39.6 percent. The IRS data also provide information on the incomes of tax filers in the 95th through the 99th percentiles of incomes — that is, those in the top five percent of tax filers, except for those in the top one percent. Nearly all those tax filers in the 95th to 99th percentiles are in the 28 percent, 31 percent, or 36 percent bracket.

- The average before-tax income of the top one percent of tax filers rose 51 percent between 1992 and 1998, after adjusting for inflation. (We measure changes in income between 1992 and 1998, because 1992 is the year before the 36 percent and 39.6 percent marginal tax rates were established, while 1998 in the latest year for which these IRS data are available.)

- The before-tax income of those in the 95th to 99th percentiles also increased significantly, climbing 21 percent.

- In contrast, the before-tax income of the bottom 95 percent of tax filers rose a more modest nine percent.

These figures — as well as the robust growth in the economy in recent years — are not consistent with theories that the increases in the top marginal tax rates enacted in the early 1990s sapped risk-taking, entrepreneurship, and work effort among high-income individuals.

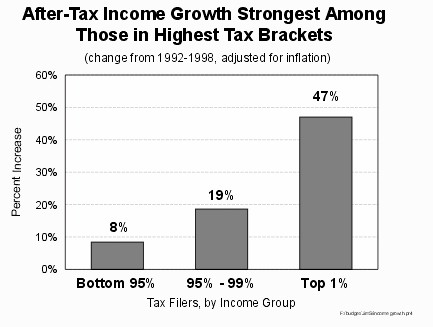

The trends in after-tax incomes are similar:

- Between 1992 and 1998, the average incomes of the top one percent of tax filers rose 47 percent after federal income taxes are subtracted. The average after-tax income of these taxpayers increased from $405,000 in 1992 to $595,000 in 1998, after adjusting for inflation, a gain of $190,000 per filer.

- Among tax filers in the 95th to 99th percentiles of income, average after-tax income rose 19 percent during this period.

- Among the rest of the population, after-tax income increased eight percent.

- The average after-tax increase of $190,000 among the top one percent of tax filers is several times greater than the total after-tax income of the typical American family.

We also examine data from 1989 (before the top marginal income tax rate was increased as part of deficit reduction legislation enacted in 1990) to 1998. The findings from this longer period are essentially the same — after-tax income has become concentrated to a much greater degree at the top of the income spectrum despite the increases in the top marginal tax rates that occurred during this period.

Joint Tax Committee Also Shows

Increasing Income Concentration

This increased concentration of income is similarly in evidence in tables the Joint Committee on Taxation released on February 27. As recently as last June, the Joint Committee was projecting that the top one percent of taxpayers would receive 13.7 percent of the national after-tax income in 2001. The Joint Committee now estimates that these taxpayers will receive 15.7 percent of the national after-tax income this year. This reflects a large upward revision in the Joint Committee's estimate of the average after-tax income of those in the top one percent of the population. The Joint Committee has raised its estimate of the average after-tax income these families will receive in 2001 by nearly $120,000 — from $589,000 in the estimate the Joint Committee issued in June to $708,000 in the new estimate.

This recent widening of income disparities is a continuation of a longer-term trend. Data from the Congressional Budget Office, which extend back to 1977 and run through 1995, show that disparities in after-tax income grew substantially between the late 1970s and 1995. Census data on before-tax income that go back to 1947 similarly show that income disparities have been increasing since the mid-1970s. These various data indicate that income disparities are greater now than at any time recorded since the end of World War II.

Conclusion

| After-tax incomes have climbed sharply in recent years among those at the top of the income spectrum and particularly among individuals in the tax brackets in which marginal rates were raised in the 1990s. Income has become more concentrated; those at the top receive a larger share of the national after-tax income than at any time on record. |

These data demonstrate that after-tax incomes have climbed sharply in recent years among those at the top of the income spectrum and particularly among those who fall in the tax brackets in which marginal rates were increased in the 1990s. The data also show that those at the top of the income spectrum receive a larger share of the national after-tax income than at any other time on record.

These patterns suggest that any tax cut should tilt against these trends or, at a minimum, not exacerbate them. While providing some tax reductions to high-income individuals may be appropriate, a tax-cut package should not be structured in a way that further widens the already vast income disparities between those at the top and other Americans. This goal can be achieved only if the share of the tax cuts that high-income families receive is no greater than their share of the national after-tax income. The Administration's tax proposal, as well as the bill that the House of Representatives passed on March 8, fail to meet this standard.

| At a time when income disparities in the United States are the widest on record, the Administration's proposal and the House-passed bill would enlarge the income gulf. |

An analysis by Citizens for Tax Justice, using the Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy model, finds that the top one percent of taxpayers would receive 44 percent of the tax cut benefits under the House-passed bill to create a new 10-percent bracket and reduce marginal rates. This 44 percent share of the benefits is more than two and one-half times the share of after-tax income these individuals receive.

In addition to the income tax provisions in the House bill, the plan President Bush submitted to Congress on February 8 would make numerous other changes, such as addressing the marriage penalty relief, expanding the child credit, repealing the estate tax, and extending the research and experimentation credit. Combining CTJ data on all of the income tax provisions in the Bush tax plan with Treasury Department data on the distribution of estate and corporate income taxes provides an estimate that the top one percent of taxpayers would receive 39 percent of the tax cuts in the overall Bush plan. That is more than double their share of the national after-tax income.

Because the top one percent of taxpayers would receive a share of the tax-cut benefits would generate that exceeds the share of the national income they already get — and most other income groups would receive a share of the tax cut that is smaller than the share of income they currently get — the tax proposal would further widen income disparities. This widening of income disparities is clearly illustrated when one looks at the change in after-tax incomes resulting from the two tax-cut proposals:

- Under the House-passed bill, after-tax incomes of the top one percent of taxpayers would rise by 3.8 percent, or three times the 1.2 percent increase in the after-tax incomes for the 20 percent of families in the middle of the income spectrum.

- Under the Bush plan, after-tax income for the top one percent of taxpayers would grow by 6.2 percent. This is three times the income growth of 1.9 percent for the fifth of the population in the middle of the income spectrum.

At a time when income disparities in the United States are the widest on record, the Administration's proposal and the House-passed bill would enlarge the income gulf.

End Notes:

1. As noted, from 1989 to 1998, the share of income taxes paid by the top one percent of tax filers rose from 25.2 percent to 34.8 percent. If the top one percent had paid the same percentage of its income in income taxes in 1998 as in 1989, it would have paid 31.4 percent of all income taxes in 1998. In other words, if the average income tax burden of the top one percent of tax filers had remained the same, this group's share of all income taxes would have risen from 25.2 percent in 1989 to 31.4 percent in 1998, simply because of the increased share of the national income it received. The increasing concentration of income thus accounted for about two-thirds of the increase that occurred in the share of income taxes paid by the top one percent.