|

March 12, 2008

KYL ESTATE TAX AMENDMENT WOULD COST

NEARLY AS MUCH AS ESTATE TAX REPEAL

By Aviva Aron-Dine

Permanent repeal of the estate tax would reduce revenues by almost $1 trillion between 2012 and 2021, the first ten-year period in which its costs would be fully felt. With the economy slowing and deficits returning — and with far larger deficits projected for future years — there is increasing recognition that estate tax repeal is unaffordable.

The estate tax “reform” proposal offered by Senator Jon Kyl, however, differs little from full repeal. Senator Kyl’s proposal, offered as an amendment to the Senate budget resolution, would increase the estate tax exemption to $10 million per couple and lower the top estate tax rate to 35 percent, with a lower rate applied to part of the value of an estate. Joint Tax Committee estimates suggest that this proposal would cost at least 77 percent as much as repeal.

Under current law, the estate tax rate has already fallen to 45 percent, and the exemption level is scheduled to rise in 2009 to $7 million per couple. Making the 2009 estate tax parameters permanent — as an amendment to the budget resolution offered by Senator Max Baucus would do — would itself be quite expensive, reducing revenues by about $500 billion over the 2012-2021 period or about half as much as repeal.

But going beyond 2009 law to the Kyl proposal would add about $250 billion to the ten-year cost, and more than $300 billion if interest costs are included. All of this additional cost would go toward tax cuts for the 3 in 1,000 estates large enough to owe any tax under 2009 law: those valued at more than $7 million per couple.

Proposal Would Provide Large Windfalls to Wealthiest Estates

As noted above, under 2009 law, the estates of 997 out of 1,000 people who die will be fully exempt from tax as a result of the $7 million per-couple exemption. Thus, all of the additional cost for proposals that go beyond 2009 law would be devoted to providing more munificent tax cuts to the 3 of every 1,000 estates that are larger than $7 million per couple.

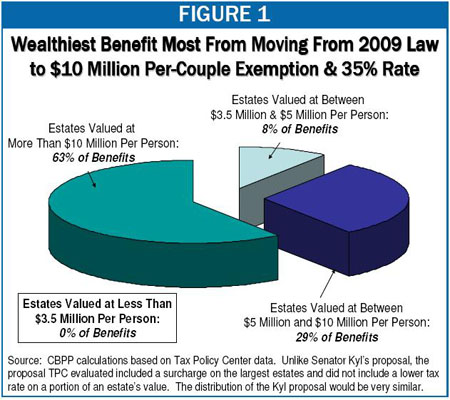

In the case of the Kyl proposal, these additional benefits would be heavily concentrated among the biggest of these very large estates. When the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center evaluated a proposal very similar to Senator Kyl’s, it found that 63 percent of the tax-cut benefits that would result from moving from 2009 law to the proposal would go to estates valued at more than $10 million per person ($20 million per couple).[1] (See Figure 1.) For these estates, the average additional tax cut — i.e., the tax cut that these estates would get on top of the tax cut they would receive from making the 2009 law permanent — would be $1.8 million per estate.

With a 35 Percent Statutory Rate, the Effective Tax Rate Would Be Less Than 14 Percent

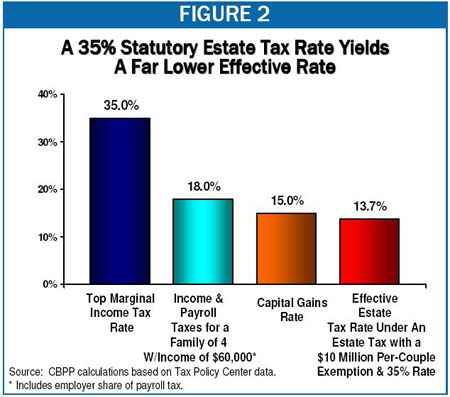

The “effective” tax rate on estates that are subject to the estate tax — the share of these estates that is actually paid in tax — is far below the top statutory rate. In part, this is because estate taxes are due only on the portion of an estate’s value that exceeds the exemption level. Under an exemption of $3.5 million per person, for example, an estate worth $4.0 million would owe tax on a maximum of $500,000. Furthermore, taxpayers can shield a large portion of the estate’s remaining value from tax by taking advantage of various available deductions and by using estate-planning strategies.

As a result, an estate tax with a 35 percent top rate and a $10 million per-couple exemption would yield an average effective rate of less than 14 percent.[2] That is, under this proposal, the heirs of the very wealthiest estates would pay tax at rates that are lower than the combined income and payroll tax rate a typical middle-income worker pays on his or her wages. (See Figure 2.)

If the 2009 estate-tax law were made permanent, the average effective rate would be 16.5 percent, still far below the top individual income tax rate, barely above the current capital gains rate, and lower than the combined income and payroll tax rate that a typical middle-income worker might face.

Making 2009 Estate Tax Law Permanent Would Shield Virtually All Farm and Small Business Estates From Tax

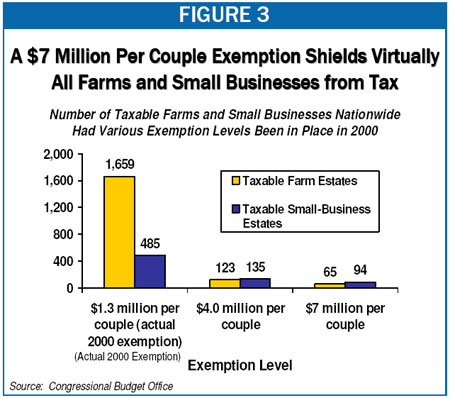

One of the major justifications Senator Kyl has offered for his amendment is that it would help family farms and businesses. But going beyond 2009 law to the Kyl proposal would help exceedingly few farms and small businesses, since virtually all such estates would already be exempt from tax under 2009 law.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that, had the $7 million per-couple 2009 estate tax exemption been in effect in 2000, only 65 farms and only 94 family-owned businesses in the entire country would have owed any estate tax.[3] (See Figure 3.) Moreover, farm and business estates also have access to additional special provisions that lower their tax bills and prevent them from ever having to liquidate a family farm or business to pay the estate tax.[4]

When the Tax Policy Center evaluated a proposal similar to Senator Kyl’s, it found that only 0.2 percent of the additional cost of the proposal, relative to making 2009 law permanent, would go toward tax cuts for small businesses and farms (businesses and farms valued at less than $5 million per person). That is, of the $250 billion additional cost of the Kyl proposal (2012-2021), only about $500 million would be spent on relief for such estates.

No Justification for Going Beyond 2009 Law

There are good reasons to consider an estate-tax reform that would be somewhat less generous than making 2009 estate tax law permanent. For example, making 2008 estate tax law — a $4 million per couple exemption and a 45 percent rate — permanent would shield 995 of every 1,000 estates from tax while preserving somewhat more revenue. As noted, under 2009 estate tax law, heirs to the wealthiest estates would still pay tax on their inheritances at lower effective rates than middle-income Americans pay on their wages. Given large deficits and serious unmet needs, it is doubtful that an estate tax reform costing $500 billion over ten years is the best use of available resources.

What should not be in doubt is that there is no justification for cuts to the estate tax that go beyond 2009 law. The additional annual cost of the Kyl proposal, relative to making 2009 law permanent — all of which would be spent on tax breaks for estates of more than $7 million per couple — is greater in today’s terms than the entire budget of the Environmental Protection Agency and is about what the federal government spends on spent on Pell Grants for low-income college students.

End Notes:

[1] These Tax Policy Center estimates are for a proposal offered in 2006 by Senator Mary Landrieu that featured a $10 million per-couple exemption and a 35 percent rate but also included a small surcharge on estates valued at more than $100 million and did not include a lower rate for smaller taxable estates. The distribution of the benefits of the Kyl proposal should be very similar.

[2] As noted above, these Tax Policy Center estimates are for Senator Landrieu’s proposal. Senator Kyl’s proposal, which includes no surcharge and a lower rate on smaller taxable estates, would generate even lower effective rates.

[3] Congressional Budget Office, “Effects of the Federal Estate Tax on Farms and Small Businesses,” July 2005, http://cbo.gov/ftpdocs/65xx/doc6512/07-06-EstateTax.pdf.

[4] See Aviva Aron-Dine, “An Unlimited Exemption for Farmland: Unnecessary, Open to Abuse, and Likely to Hurt Rather Than Help Family Farmers,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 1, 2007, https://www.cbpp.org/10-1-07tax.htm. |