The State Tobacco Settlements:

What Should be Done with the Federal Share

of Medicaid-Related Tobacco Payments?

by Cindy Mann,

Andy Schneider, and Sara Thom

Table of Contents IV. Offsetting Federal Program Cuts V. Long-term Effects of Transferring the Federal Share of Settlement Funds to the States VI. Conclusion |

Overview

All states expect to receive large ongoing tobacco settlement payments as a result of the master settlement with the tobacco manufacturers or previously settled tobacco litigation. The parties to these agreements estimate that states will receive tobacco payments totaling $36.5 billion through 2002 and $239.5 billion through 2025.(1) In exchange for these payments, the states relinquish all claims against the tobacco manufacturers relating to the costs of treating Medicaid beneficiaries for tobacco-induced illnesses.

On average, the federal government pays 57 percent of the costs of providing medical services to Medicaid beneficiaries. The federal government's tobacco-related Medicaid costs are substantial. Estimates developed by the states' experts in the course of the tobacco litigation suggest the federal share of all tobacco-related Medicaid costs will be in the range of $9.0 billion to $13.3 billion in FY 2000, reaching $53.7 billion to $79.8 billion over the five-year period from 2000 through 2004.

Since the federal government shares the cost of Medicaid services with the states, federal Medicaid law requires states to share the proceeds from Medicaid third-party recoveries with the federal government. The states, however, take the position that the federal government should not receive any portion of these tobacco settlement payments. Delaware Governor Thomas R. Carper, the chairman of the National Governors Association, and Utah Governor Michael O. Leavitt, NGA vice chair, have stated that "states initiated this settlement and accordingly states should receive the full funding from the tobacco industry without the threat of federal seizure of funds."(2) The states' position ignores several important points:

- Under federal Medicaid law, the states — rather than the federal government — are responsible for seeking recoveries for Medicaid-related costs from third parties such as tobacco manufacturers. Although the federal government can pursue Medicare claims against tobacco manufacturers, it has no legal authority to pursue Medicaid claims directly. Only states can sue to recover Medicaid third-party claims. The federal government's sole means for recovering any portion of its substantial tobacco-related Medicaid costs is through recovery actions initiated by the states.

- The states did not bear the full risk of the cost of tobacco

litigation. When states pursue third-party Medicaid claims, the federal government

shares half the cost of these collection efforts. The federal government is legally

required to reimburse states for such costs whether a state wins or loses its litigation.

Moreover, the fee arrangements between states filing tobacco litigation and the private firms they engaged indicate that private attorneys bore at least a portion of the risks associated with these suits. According to a National Law Journal report, contingency fee agreements were negotiated with respect to tobacco lawsuits filed in 36 states.(3)

- If Congress adopts legislation that would turn over the federal government's share of the Medicaid-related tobacco payments to the states, offsetting savings would need to be identified. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that such legislation would cost the federal Treasury $2.9 billion from 1999 to 2004 and $6.8 billion over the 10-year period ending in 2009.(4) Under federal budget rules, such costs would have to be "paid for" with savings from Medicaid, Medicare or other federal entitlement programs or a tax increase.(5)

The course favored by the states could lead to anomalous results. The reductions in federal expenditures that would be needed to offset the cost of allowing the states to keep the federal portion of the Medicaid-related tobacco payments could prompt a reduction in federal Medicaid expenditures and potentially result in reductions in coverage and/or services for Medicaid beneficiaries. Moreover, there would be no guarantee that the Medicaid-related resources retained by the states would be used for health initiatives. Once the states receive these federal funds, the funds could be spent on any state initiative, including special-interest tax cuts and pork-barrel projects. Meanwhile, the federal government would continue to pay states its share of the costs of treating the tobacco-induced illnesses of Medicaid beneficiaries. In addition, the federal government would have lost its only opportunity to be compensated by the tobacco manufacturers for at least a portion of the tobacco-related Medicaid costs that it bears.

These unbalanced outcomes can be avoided. Congress need only leave current Medicaid law intact, allowing the federal government to recover some of its tobacco-related Medicaid costs from the manufacturers' payments. By maintaining both the federal government's ongoing obligation to share tobacco-related Medicaid costs with the states and the states' responsibility to share Medicaid-related third-party recoveries with the federal government, responsibilities and obligations for tobacco-related Medicaid costs would be spread fairly.

At a minimum, if legislation is enacted allowing the states to retain the federal government's share of Medicaid-related tobacco payments, such legislation should be designed so it does not prompt cutbacks in federally-funded health programs. It also should require states to use the federal share of these Medicaid-related funds for new health services and coverage for low- and moderate-income individuals and families, consistent with the purposes of the Medicaid program and the tobacco litigation. In addition, such legislation could limit the period of time during which states would be permitted to retain the federal portion of these settlement funds. This would assure that these funds were available at the federal level at a time when the federal budget may no longer be in surplus. For example, rather than turning these federal payments over to the states in perpetuity, Congress could forgo the federal share of the settlement payments for 10 years after which the federal government would begin to receive its share of the annual payments.

The Settlement Payments Include Reimbursement to the States for their Tobacco-Related Medicaid Costs

On November 23, 1998, forty-six states, the District of Columbia, and five territories agreed to settle pending litigation with the tobacco manufacturers, and to refrain from bringing suit on new claims against those manufacturers, in exchange for annual payments that will continue in perpetuity. According to estimates the parties have made, payments to states under the master settlement will amount to $67.6 billion between 1998 and 2008 and $195.9 billion between 1998 and 2025. The other four states — Florida, Mississippi, Texas, and Minnesota — individually settled their lawsuits with the manufacturers prior to this master agreement; the estimated payments to these states total $43.6 billion through 2025.(6) The parties estimate that industry payments to all states under these settlements will amount to $36.3 billion through 2002 and to $239.5 billion through 2025.

While the settlements do not specify what portion of the payments is attributable to tobacco-related Medicaid costs, Medicaid claims were the centerpiece of the litigation the states initiated. It is indisputable that the settlement payments by the tobacco manufacturers are, in substantial part, designed to reimburse states for Medicaid costs.

Calendar Year |

Payments to States |

| 1998 | $2.40 |

| 1999 | $0.00 |

| 2000 | $6.41 |

| 2001 | $6.92 |

| 2002 | $8.31 |

| 2003 | $8.39 |

| 2004 | $7.00 |

| 2005 | $7.00 |

| 2006 | $7.00 |

| 2007 | $7.00 |

| 2008 | $7.14 |

| 10-Year Total | $67.60 |

Source: National Association of Attorneys General, "Annual Payments to Each State", www.naag.org/tob2.htm |

|

In June 1997, before any of the individual state settlements were achieved, the Attorney General of Indiana sent a memorandum to all suing Attorneys General which makes clear that Medicaid recoveries were central to the state lawsuits. The memorandum, which proposes a formula for the distribution of tobacco settlement funds among the states, explains that "[s]tates are in the business of administering Medicaid, and Medicaid reimbursement was the primary element of damages for most, if not all, suing States." In a footnote, the memo elaborates: "We realize, of course, that most States also sued on other theories such as antitrust, RICO, and consumer protection. States have in common, however, the desire for Medicaid reimbursement."(7)

Moreover, the settlement agreements extinguish any legal claims the states have against the tobacco manufacturers to recover past or future Medicaid costs attributable to smoking-induced illness. For example, under the master settlement agreement, each participating state agrees to "absolutely and unconditionally release and forever discharge" the tobacco manufacturers from monetary claims directly or indirectly based on the use of tobacco products, including "without limitation any future Claims for reimbursement of health care costs allegedly associated with the use or exposure to Tobacco Products."(8) In addition, the "model statute" that each participating state is required to adopt to receive its full allotment under the master settlement provides that a purpose of this settlement is to address the state's "financial concerns" relating to its legal obligation to provide medical assistance to persons with tobacco-related illnesses who may have a legal entitlement to receive such medical assistance.(9) While Medicaid is not named in this model statute, the references clearly contemplate the Medicaid program.

Moreover, the distribution of the proceeds of the master settlement to the states closely mirrors each state's share of Medicaid-related tobacco expenditures. Citing the Colorado Attorney General, the Wall Street Journal reported that the amounts each state will receive under the master settlement "will depend on the numbers of Medicaid recipients on each state's rolls, the cost of medical services and the amount each state contributed to Medicaid coverage historically."(10)

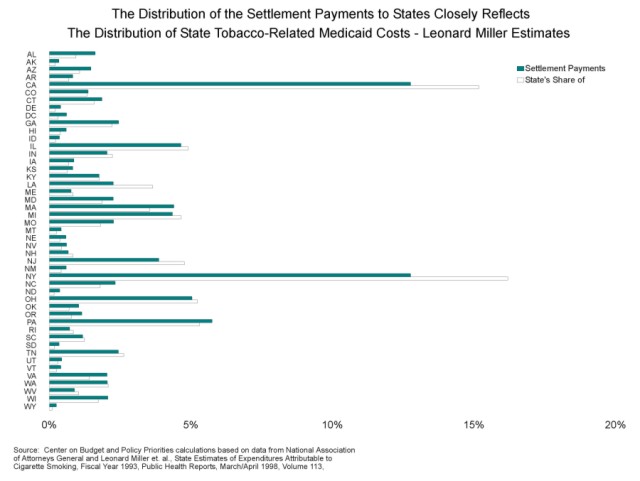

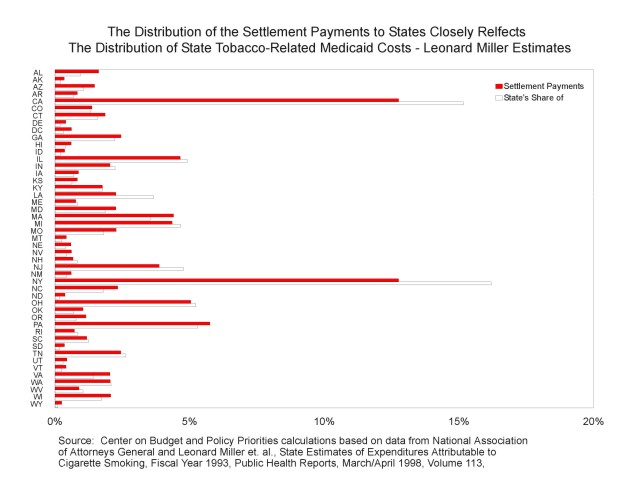

There is a striking relationship between tobacco-related Medicaid expenditures for each state and the distribution of the tobacco settlement funds. The graphs on the following page plot participating states' share of the master settlement against each state's share of Medicaid expenditures for tobacco-related illnesses. Two sets of estimates of tobacco-related Medicaid costs by state were prepared for the states in connection with their tobacco litigation — one by University of California-Berkeley professor Leonard S. Miller, et. al,(11) and one by Vincent Miller and his colleagues from the Berkeley Economic Research Associates (BERA).(12) The distribution among the states of the funds from the settlements has a 98 percent correlation with the distribution of tobacco-related Medicaid costs among the states as estimated by Leonard Miller, and a 96 percent correlation with the distribution of these costs as estimated by BERA. (See Figures 1 and 2 below.)

The Federal Government's Legal Entitlement to a Share of the Medicaid-related Tobacco Settlement Payments

Federal Medicaid law requires that states electing to participate in the Medicaid program take "all reasonable measures" to identify responsible third parties and recover from them payments for the costs of services that Medicaid purchases on behalf of eligible individuals.(13) For example, if a Medicaid beneficiary is injured in an automobile accident and Medicaid pays for the required emergency services, the state is responsible for recovering the costs of those services from the automobile insurer. In the case of the costs of treating tobacco-related illnesses that Medicaid covers, the liable third party is not an automobile insurer but the tobacco industry.

For more than 30 years, federal Medicaid law has provided that any funds states recover from liable third parties must be shared between the state and the federal government in proportion to their respective shares of the costs of Medicaid services. The federal Medicaid matching rate varies from 50 to 80 percent depending on the state's per capita income; on average, the federal government pays 57 percent of the cost of program services. The federal government thus is entitled, on average, to 57 percent of any Medicaid recoveries from liable third parties.

Liable tobacco manufacturers are no exception. As the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services informed state Medicaid directors last year, "Under current law, tobacco settlement recoveries must be treated like any other Medicaid recoveries."(14) This means that as states receive their settlement payments each year from the tobacco manufacturers, HCFA would recoup the federal share of the payments attributable to Medicaid costs by reducing the amount of federal matching payments a state would otherwise receive. Consider a state with a 50 percent federal Medicaid matching rate that is otherwise entitled to $100 million in federal Medicaid matching funds in a quarter. If the state received a tobacco settlement payment in that quarter of $10 million of which $5 million was determined to be Medicaid related, then $2.5 million (50 percent of the $5 million) would be owed to the federal government. HCFA would collect these funds by reducing the federal Medicaid matching payment for that quarter from $100 million to $97.5 million.

Who Bore the Risk?

The states take the position that the federal government should not recover any portion of the settlement payments because the states, and not the federal government, took the action to sue the tobacco manufacturers and bore the financial risk of the litigation. This argument is weak, however, for two reasons.

- The federal government does share the risk of litigation equally with

the states. The federal government matches, on a 50-50 basis, the costs that states incur

in recovering Medicaid funds, including litigation expenses. Federal matching funds are

guaranteed whether a state's recovery efforts are successful or not. Had the states been

unsuccessful in pressing their Medicaid claims against the tobacco manufacturers, they

could have — and most surely would have — sought federal reimbursement for half

of the litigation costs relating to these Medicaid claims. Consequently, the federal

government did bear a sizeable financial risk as a result of the tobacco litigation.

The argument that states alone bore the costs and the risks of the tobacco litigation also ignores the fact that the fee arrangements between the states and the private attorneys who pursued these claims on behalf of the states suggest that private attorneys bore at least a portion of these risks.

- The states' contention that the federal government should be barred from receiving its share of Medicaid-related settlement payments because the federal government failed to bring suit against the tobacco manufacturers to recover its tobacco-related Medicaid costs is not valid. Federal law appears to give states exclusive authority to sue to recover Medicaid costs from third parties.(15) Although the Justice Department is pursuing claims against tobacco companies to recover tobacco-related costs under Medicare and certain other federal health programs, such as veterans' programs, the federal government's sole means for recovering its share of tobacco-related Medicaid costs flows from the requirement that states pursue third-party claims and share the proceeds of Medicaid third-party recoveries with the federal government.

The Federal Government Incurs Substantial Medicaid Costs Associated with Treating Tobacco-related Illnesses

The federal government has incurred — and will continue to incur — substantial costs under the Medicaid program for treating people with tobacco-induced illnesses. One way to estimate federal tobacco-related Medicaid costs is to use the estimates prepared for the states in connection with the tobacco litigation. As noted above, two such estimates were developed. In each case, the experts estimated the Medicaid costs attributable to smoking that each state incurred in 1993. These costs include both the state and federal shares.

Using BERA's estimates, total costs equaled $8.7 billion nationally in 1993; using Leonard Miller's estimates, the overall cost was $12.9 billion. On average, 57 percent of these expenditures or $5.0 to $7.4 billion were borne by the federal government. Since total federal Medicaid expenditures on services in fiscal year 1993 amounted to $56.2 billion, 8.8 percent of federal Medicaid costs (under the BERA estimates) and 13.1 percent (under the Leonard Miller estimates) were attributable to treating tobacco-related illnesses.

To estimate the federal share of the tobacco-related costs the Medicaid program will incur in the future, these 1993 percentages can be applied to projected federal Medicaid spending levels. In making these estimates, we assume that the percentage of national Medicaid spending attributable to the treatment of smoking-induced illnesses will not vary significantly from year to year. Using this approach, the amount the federal government is projected to spend on tobacco-related Medicaid costs over the next 10 years ranges from $124.30 billion to $184.66 billion, depending on whether the BERA or the Leonard Miller estimates are used. (See Table 2.)(16)

| Fiscal Year | Projected Federal Medicaid Expenditures(17) | Low-Range Estimates of Federal Medicaid Expenditures Attributable to Tobacco (8.8% of Federal Medicaid Expenditures)(18) | High-Range Estimates of Federal Medicaid Expenditures Attributable to Tobacco (13.1% of Federal Medicaid Expenditures)(19) |

| 1999 | 92.9 | 8.17 | 12.14 |

| 2000 | 101.3 | 8.91 | 13.23 |

| 2001 | 110.3 | 9.7 | 14.41 |

| 2002 | 120.3 | 10.58 | 15.72 |

| 2003 | 130.8 | 11.5 | 17.09 |

| 2004 | 142.9 | 12.57 | 18.67 |

| 2005 | 155.8 | 13.7 | 20.35 |

| 2006 | 170.1 | 14.96 | 22.22 |

| 2007 | 185.8 | 16.34 | 24.27 |

| 2008 | 203.2 | 17.87 | 26.55+ |

| 10-year total | $1,413.40 | $124.30 | $184.66 |

Source: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities calculations based on estimates of total (federal and state) Medicaid expenditures on tobacco-related illnesses in fiscal year 1993; the "low-range" estimates are derived from estimates by Vincent Miller et. al in Smoking-Attributable Medical Care Costs: Models and Results, Berkeley Economic Research Associates, September 3, 1997, Table 5.8; www.bera.com. , and the "high-range" estimates are derived from estimates by Leonard S. Miller et. al in "State Estimates of Medicaid Expenditures Attributable to Cigarette Smoking, Fiscal Year 1993," Public Health Reports, March/April 1998, Volume 113, pp.140-151. Federal expenditures for 1993 were based on Congressional Budget Office, The Economic and Budget Outlook, Fiscal Years 1999-2008, Appendix G, Table G-2 and are net of administrative costs and disproportionate share hospital payments based on data on administrative costs from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Care Financing Administration Medicaid Statistics: Program and Financial Statistics, Fiscal Year 1993, HCFA-64-Table 1, page 132 and data on disproportionate share hospital payments from David Liska, Karen Obermaier, Barbara Lyons, and Peter Long, Urban Institute, Medicaid Expenditures and Beneficiaries, National and State Profiles and Trends, 1984-1993, July 1995, Table 39, page 91. Projections of federal Medicaid expenditures are based on CBO's March 1999 Baseline, Medicaid and Children's Health Insurance Program, Fact Sheet-March 1999. |

|||

Offsetting Federal Program Cuts

The states argue that the federal share of the portion of settlement payments attributable to Medicaid costs should be turned over to the states. This transfer of federal funds to the states would require Congress to amend the Medicaid statute relating to recoveries from liable third parties. CBO has stated it will score such legislation as a cost to the federal government. A recent CBO memorandum declares: "Any legislation that would reduce the amount of the federal share of Medicaid-related state settlement funds or the probability of HCFA retrieving those funds would increase federal Medicaid spending."(20)

Taking into account the adjustments required by the settlements, CBO assumes that states will receive $48 billion in tobacco settlement payments by 2004 and $97 billion by 2009. The extent of the federal government's share of these settlement payments under current law depends in part on what portion of these funds are determined to be based on Medicaid claims. CBO projects that about half of the tobacco payments will be determined to be Medicaid-related. It consequently estimates that the federal share of these payments would be $14 billion over five years and $28 billion over 10 years. CBO discounts the federal recovery, however, and assumes the federal Health Care Financing Administration actually will collect only one-fourth of these federal funds from the states. Thus, CBO estimates that federal tobacco-related recoveries from the states will begin in 2001 and amount to $2.9 billion for the five years ending in 2004 and $6.8 billion over the ten-year period from 1999 to 2009.

Federal budget law requires that if these funds are turned over to the states, the resulting cost to the federal Treasury must be "paid for" through offsetting reductions in Medicaid, Medicare, or other federal entitlement programs or through a tax increase.(21) Even if the necessary offsets can be found, applying them to legislation allowing the states to keep the federal share of Medicaid-related tobacco settlement recoveries would preclude their use to help finance other federal initiatives, including health and other tobacco-related initiatives.

Long-term Effects of Transferring the Federal Share of Settlement Funds to the States

CBO's estimates reflect the cost over five years and 10 years of legislation implementing the states' position. Since such legislation would alter federal Medicaid law permanently, the loss to the federal government of its share of funds would continue indefinitely, rather than ceasing at the end of the 10-year period. Over the 27-year period from 1998 to 2025, the federal government would be giving up its share of $239.5 billion in tobacco payments to the states.

Although the exact amount of the federal share of these payments is unknown (because the adjustments of the state settlement payments required under the master settlement have not been estimated), the wisdom of turning over substantial federal resources to the states in perpetuity is questionable. Although the federal budget currently is in surplus, this will not always be the case. CBO's latest projections indicate that even if none of the projected budget surplus is used for tax cuts or spending increases, deficits will return some time after 2020 and eventually climb to record levels for periods other than wars or recessions. If Congress and the President use much or all of the projected surpluses in the non-Social Security budget for program or tax-cut initiatives, as seems very likely, the deficit will return sooner. If Congress amends the Medicaid statute to allow states to continue retaining in perpetuity the federal share of tobacco settlement payments, one likely effect will be deeper cuts in federal programs, larger tax increases, or still-greater deficits when the nation's fiscal problems return.

Congress should not readily relinquish the federal government's claim to these Medicaid-related tobacco funds. The federal government has no other means by which it can recover from the tobacco manufacturers any portion of the substantial costs it has incurred, and will continue incurring, in treating Medicaid beneficiaries for tobacco-related illnesses.

If Congress does relinquish its claim to its share of the settlement payments, the cost of such legislation should not be offset through reductions in Medicaid or other low-income or health programs, and the legislation should include provisions assuring that states use these relinquished federal funds for health-related benefits and services consistent with the purposes of the Medicaid program. In addition, if Congress passes such legislation, rather than turning these federal payments over to the states in perpetuity, it may want to consider allowing states to retain these federal Medicaid-related tobacco payments only for a specified period of time. For example, Congress could forego the federal share of the settlement payments for 10 or 15 years, after which the federal government would begin to receive its share of annual payments to avoid potentially damaging long-term federal fiscal consequences.

End Notes:

1. National Association of Attorneys General, www.naag.org/tob2.htm. In general, the estimates of payments that will be made through the master settlement are based on the annual payments that states are expected to receive before a number of adjustments, including an adjustment for inflation. These estimates do, however, reflect the "previously settled states adjustment," a reduction in state payments designed to account for tobacco manufacturers' payments to the four states that reached agreements prior to the master settlement agreement. States can begin to draw down their tobacco settlement funds on June 30, 2000 or after 80 percent of the states and states that account for 80 percent of the total settlement funds have received final approval from a state court for their participation in the master settlement agreement, whichever occurs first.

2. National Governors Association, Press Release: State Leadership Clinches Tobacco Deal, November 20, 1998.

3. Bob Van Voris, That $10 Billion Fee", National Law Journal, November 30, 1998. According to press reports, arbitration of the fees for the trial attorneys representing Florida, Mississippi and Texas in their individual settlements resulted in an award totaling $8.2 billion. Ann Davis, Arbitration for Fees in Tobacco Suit Reflects Lobbying, Wall Street Journal, December 14, 1998, B2. The arbitration of attorneys' fees under the master settlement agreement has not yet occurred.

4. CBO memorandum, Tobacco-related Medicaid Recoveries in the CBO January 1999 Baseline, January 25, 1999. The assumptions underlying this estimate are discussed at pages 12.

5. Legislation to transfer the federal share of Medicaid-related tobacco recoveries to the states would be subject to a point of order in both the House and the Senate if the cost of the legislation were not offset by reductions in entitlement programs or tax increases. If such a point of order were overridden and the legislation were enacted without offsetting savings, the "Pay-As-You-Go" rules would require OMB to impose cuts on Medicare and other mandatory programs to pay for the cost of the legislation. The level of cuts made through this procedure, known as sequestration, would depend upon OMB's (rather than CBO's) estimates of the cost to the federal government of allowing states to retain the federal share of Medicaid-related tobacco settlement payments. Since OMB does not assume any federal tobacco recoveries in its baseline, a sequester would not be likely. Nevertheless, the Congress generally acts in accordance with CBO rather than OMB cost estimates and consequently may require an offset if the legislation sought by the states is adopted.

6. Memorandum of Understanding, State of Mississippi Tobacco Litigation, pp. 2-3, July 3, 1997, (http://stic.neu.edu/MS/Mssettle.htm); Settlement Agreement, State of Florida v. American Tobacco Company et. al., paragraph II.B, August 25, 1997 (http://stic.neu.edu/FL/FLsettle.htm); Comprehensive Settlement Agreement and Release, State of Texas v. American Tobacco Company et. al., pp. 6-7, January 16, 1998 (http://stic.neu.edu/TX/Texas-settlement.htm); Settlement Agreement and Stipulation for Entry of Consent Judgement, State of Minnesota v. Phillip Morris Incorporated et. al., pp. 6-8, May 8, 1998 (http://stic.neu.edu/MN/settlement.htm); Attorney General Mike Moore, News Release, Attorney General Announces An Additional Half Billion Dollars for Mississippi, July 7, 1998; Mark Curriden and Richard Oppel, Jr., State Tobacco Settlement May be Imminent: Cigarette Makers Agree to Pay State An Extra $2.28 Billion, Dallas Morning News, July 16, 1998; Florida Attorney General Bob Butterworth, News Release, Governor, AG Announce $1.7 Billion More From Tobacco Case, September 18, 1998, (http://legal1.firn.edu/newsrel.nsf).

7. Attorney General Jeff Modisett, Memorandum to All Suing Attorneys General, "Draft Proposal for Tobacco Settlement Distribution Formula," June 23, 1997, p. 3.

8. Master Settlement Agreement, subsections XII(a)(1) and II(nn)(2).

9. Master Settlement Agreement, model statute, Exhibit T. Under the agreement any state that fails to enact such a statute will experience a reduction in its allotment of up to 65 percent.

10. Milo Geyelin, "States Agree to $206 Billion Tobacco Deal," Wall Street Journal, November 23, 1998, B13.

11. Leonard S. Miller, et. al. State Estimates of Medicaid Expenditures Attributable to Cigarette Smoking, Fiscal Year 1993, Public Health Reports, March/April 1998, Volume 113, pp. 140 - 151.

12. Vincent Miller et. al, in Smoking-Attributable Medical Care Costs: Models and Results, Berkeley Economic Research Associates, September 3, 1997, Table 5.8. www.bera.com.

13. Section 1902(a)(25) of the Social Security Act.

14. Letter from Sally K. Richardson, Director, Center for Medicaid and State Operations, HCFA, to State Medicaid Directors, November 3, 1997.

15. Statement of Nancy-Ann Min Deparle, HCFA Administrator, Medicaid and Tobacco Settlements", submitted to the House Committee on Commerce, Subcommittee on Health and Environment, December 8, 1997.

16. Projected Medicaid spending levels are based on CBO's January 1999 Medicaid baseline.

17. Congressional Budget Office, January 1998 baseline. (Get more specific cite).

18. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities calculations based on estimates of total (federal and state) Medicaid expenditures on tobacco-related illnesses in fiscal year 1993, developed by Vincent Miller et. al in Smoking-Attributable Medical Care Costs: Models and Results, Berkeley Economic Research Associates, September 3, 1997, Table 5.8. www.bera.com.

19. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities calculations based on estimates of total (federal and state) Medicaid expenditures on tobacco-related illnesses in fiscal year 1993, developed by Leonard S. Miller et. al in State Estimates of Medicaid Expenditures Attributable to Cigarette Smoking, Fiscal Year 1993, Public Health Reports, March/April 1998, Volume 113, pp.140-151.

20. CBO Memorandum, Tobacco-related Medicaid Recoveries in the CBO January 1999 Baseline, January 25, 1999.

21. OMB, however, does not assume any tobacco recovery payments in its Medicaid baseline. See footnote 5, infra.