|

Revised December 19, 2006

ASSESSING THE IMPACT OF STATE ESTATE TAXES

By Elizabeth McNichol

In June 2001, President Bush signed federal legislation to phase out the federal estate tax. This legislation repeals the federal estate tax by 2010 and also effectively repealed by 2005 the state “pickup” taxes through which states share in federal estate tax collections. States can prevent this loss of revenue by “decoupling” from the federal change and, as of December 2006, 17 states plus the District of Columbia were decoupled from the federal changes.[1]

There have been a number of reports concerning the impact of state estate taxes in states that have decoupled from the federal changes. This is a complicated topic; the effect on individual estates varies over time and is very dependent on the size of a person’s estate. If examined out of context, the effects of maintaining a state estate tax can be significantly overstated and lead one to erroneous conclusions.

For example, some reports suggest that people — especially elderly people — should be very concerned about where they live because of the potential impact of state taxes on their ability to pass along accumulated savings and property to their heirs. In fact, however, the vast majority of people are unaffected by these taxes. For those whose estates are large enough to be affected, the difference between living in a state with or without an estate tax can be small. Other reports give the impression that estate taxes are increasing rather than declining over time in states that have retained their state estate tax. This also is incorrect. This report addresses some facts about state estate taxes that will help put their actual impact in perspective.

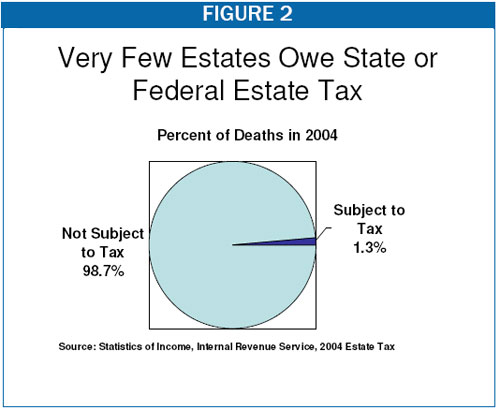

A state’s estate tax — like the federal estate tax — will have no effect on the vast majority of people. Very few people are affected by estate taxes – state or federal. Nationally, less than 2 percent of estates — those of the wealthiest people — are large enough to have any estate tax liability. The over 98 percent of people who will leave a net estate that is valued at less than the minimum required to trigger state estate taxes — $675,000 to $2 million depending on the state — will not be affected by the state tax. In addition, anyone passing their estate on to a spouse will not owe any estate tax — state or federal.

Total estate taxes will decline for all estates, whether the person leaving the estate lived in a state that has retained an estate tax or not. No matter how large a person’s estate is, the 2006 federal and state combined estate tax bill for that estate will decline compared to prior law. The reduction in the bill is smaller in states that retain an estate tax than in other states, but this is because the federal government eliminated the credit for state estate taxes, not because states have raised their estate taxes. Even in those states that are retaining their state tax, the amount that federal estate taxes are going down outweighs the fact that the federal government will no longer give a credit for state estate taxes.

The fact that the state estate tax is being retained by some states but not by others should not affect where people live. Studies show that most people choose their residence based on things such as closeness to a good job and family members, the state’s climate, and access to services such as health care, not because of the estate tax rate of a state. A state’s decision to retain an estate tax won’t change these features. In fact, the revenue that the state keeps could help pay for public services — nurses and state troopers’ salaries, roads, arts centers, housing and more that can make a state more attractive. And, it could allow the state to avoid raising other taxes such as sales or income taxes that affect many more people.

The amount of state estate tax owed by estates that are large enough to be taxable is less than it might appear based on the rate schedule. Most states that have retained an estate tax based on the federal credit continue to use the schedule for the “state death tax credit” that was part of the federal estate tax law in 2001.[2] This is a graduated rate schedule that sets the credit – and thus the amount of the state tax — to a proportion of the value of the estate. The tax rate increases as the size of the estate increases. (See Appendix table 2.) The top marginal rate is 16 percent and this rate is often cited as the bite that state estate taxes will take. In fact, this significantly overstates the impact of the tax.

-

While the federal government has repealed the credit for state estate taxes paid, they replaced it with a deduction against the value of the estate.[3] As a result, the effective state estate tax rate is much less than 16 percent. (See below for more detail.)

-

For example, consider someone with $2.5 million in assets to pass on to their heirs. If this person died in 2006 while living in a state that has retained its tax, the state tax will equal 3.0 percent of the estate. This effective rate of 3.0 percent of the estate is well under 16 percent.

In sum, the fact that some states are retaining their estate taxes even though the federal government is eliminating the credit for state taxes and replacing it with a deduction will affect very few people. For those who are affected, the impact is not one that is significant enough to prompt major life style changes such as moving to another state.

What Will a State’s Estate Tax Cost a Typical Estate?

The amount of combined federal and state estate tax that an estate will owe depends on many factors, including whether the death occurs in a state that has retained its state estate tax or not. The sections below discuss the effect of the retention of a state estate tax on an estate’s tax bill. This effect — like the total estate tax bill — varies by year of death and by the size of the estate. Review of existing data on estates and analysis of the provisions of the federal estate tax law lead to the following conclusions.

The vast majority of estates will owe no federal or state estate tax. According to figures from the Internal Revenue Service for deaths occurring in 2004 – the most recent data available — some 30,276 estates owed some estate tax. These estates made up just 1.3 percent of deaths. Put another way, fully 98.7 percent of estates owed no estate tax.[4]

The vast majority of estates that do owe tax are valued at less than $10 million so they are not subject to the top marginal rate of state estate taxes. Table 1 shows the breakdown of taxable estates by size of estate. Only a small fraction of taxable estates – 4.4 percent — are valued at more than $10 million. Some nine of ten estates are valued at less than $5 million and 70 percent of these estates are valued at less than $2.5 million. The median value for an estate subject to tax in 2001 was between $1 and $1.5 million. Most taxable estates are clustered at the lower values and pay far less than the maximum state rate.

|

Table 1:

Distribution of Estates by Size of Estate - 2004 |

| Size of Estate |

Number |

Percent of Total |

Cumulative |

| $1 million to $2.5 million |

21,152 |

69.9% |

69.9% |

| $2.5 million to $5 million |

5,630 |

18.6% |

88.5% |

| $5 million to $10 million |

2,166 |

7.2% |

96.5% |

| $10 million to $20 million |

808 |

2.7% |

98.3% |

| $20 million plus |

520 |

1.7% |

100.0% |

| Total |

30,276 |

100.0% |

|

-

As noted above, the typical estate owes no state or federal estate tax and is not affected by the level of those taxes. An estate must be valued at more than $2 million to be subject to the federal estate tax. The minimum value for an estate to owe a state’s estate tax ranges from $675,000 to $2 million.

-

According to the Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances, the median net worth of U.S. families was $93,100 in 2004. This figure includes the value of their home, personal belongings and financial assets such as savings accounts reduced by any outstanding debt such as mortgages and auto loans. The typical family in the U.S. has a net worth that is far below the level that would trigger any estate tax liability.

The two examples below illustrate the effect of state estate taxes on the small minority of estates that are potentially subject to estate taxes.

Impact on Estate Valued At $2.5 Million

First, the effect of retaining a state estate tax on an estate of $2.5 million in a state that has ‘partially decoupled’ from the federal changes is considered. (A state that has partially decoupled has retained its estate tax by setting the amount of the tax equal to the credit as it stood in 2001 but has adopted the higher federal exemptions of the current federal law.)

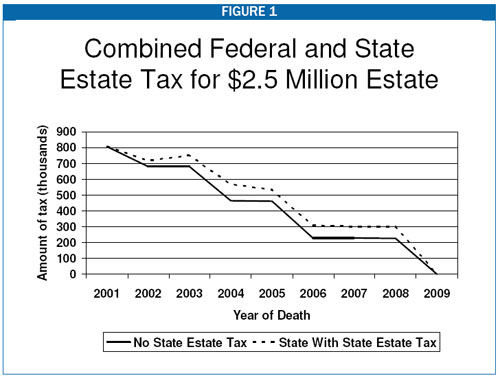

In 2005 the combined federal and state estate taxes owed by an estate of this size will have dropped from $805,250 to $533,564 – a substantial reduction of $271,686 (33.7 percent) in a state that has retained its estate tax. In a state that did not retain its tax, the reduction is $345,350 (42.9 percent).

Figure 1 shows the change in estate tax liability for an estate of $2.5 million in a state that has retained its state tax compared to one that has not. In both cases the estate taxes owed are declining dramatically. By 2009, an estate of this size will owe no tax in either case.[5]

|

Table 2:

Additional Tax Owed by $2.5 Million Estate in State that has Retained a State Tax |

|

Year |

Tax (as percent of estate) |

|

2003 |

2.8% |

|

2004 |

4.2% |

|

2005 |

2.9% |

Starting in 2005, the retention of a state estate tax raises the effective rate of the estate tax by about 3 percent for an estate of this size. Table 2 shows the additional amount of tax that would be would be owed by a $2.5 million estate in 2003, 2004 and 2005. The reason the rate is higher is 2004 is because this is the last year that the credit for state taxes paid remained in the federal law and it will equal 25 percent of taxes paid. A 25 percent credit is of less value to an estate than the deduction that will replace it in 2005 and beyond. Thus the effective rate of state estate taxes is higher in 2004 than in 2003 and also higher than in 2005 and beyond.

Impact on Estate Valued At $1.5 Million

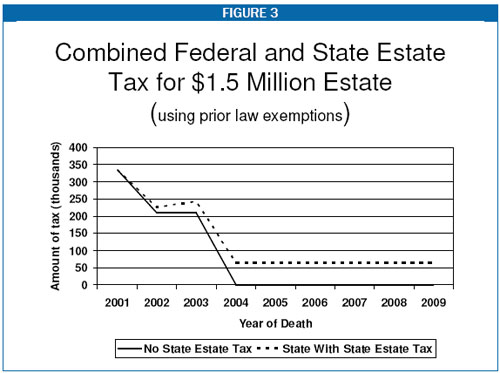

The effect of retaining a state estate tax on an estate of $1.5 million in a state that has ‘completely decoupled’ from the federal changes will be somewhat larger relative to the size of the estate. (A state that has completely decoupled is one that has retained its estate tax by setting the amount of the tax equal to the credit as it stood in 2001 and is also using the federal exemptions that were in effect in 2001 rather than the higher ones of current law.) The effective rate will be greater because the federal exemption equals $2 million in 2006. As a result, there is no federal estate tax liability for an estate of this size. So, the federal deductability of state estate taxes is of no benefit.

By 2005, the combined federal and state estate taxes owed by an estate of this size had dropped from $335,250 to $64,400 – a reduction of $ 260,850 (80.1 percent) in a state that has retained its estate tax. In a state that did not retain its tax, the reduction is $335,250 (100.0 percent). In both cases, as Figure 3 shows, the estate taxes owed decline dramatically.

Starting in 2005, the retention of a state estate tax raises the effective rate of the estate tax by about 4.3 percent for an estate of this size. Table 3 shows the additional amount of tax that would be owed by a $1.5 million estate in 2003, 2004 and 2005. The reason the rate is higher is 2004 and beyond is because the federal exemption rises to $1.5 million in 2004 so there is no federal tax to be offset by the credit or deduction for state estate taxes paid.

|

Table 3:

Additional Tax Owed by $1.5 Million Estate in State that has Retained a State Tax |

|

Year |

Tax (as percent of estate) |

|

2003 |

2.1% |

|

2004 |

4.3% |

|

2005 |

4.3% |

Impact On Larger Estates

For the minority of estates with a value of more than $2.5 million, the effective rate of a state estate tax will range from 3 percent for estates valued at just above $2.5 million to about 9 percent for the very few estates valued at $100 million or more.

Impact In 2010 And Beyond

These examples show the effect of a state estate tax on “typical” taxable estates between now and 2009. The effect in 2010 and beyond depends on whether the federal government acts to further modify the federal estate tax between now and 2010.

As the law currently stands, the federal estate tax is repealed in 2010. As a result, the effective rate of state estate taxes will be higher in 2010 than in 2009 because of the loss of federal deductability. However, in 2011 and beyond the federal estate tax will return at the 2001 level. If this stands, the effective rate of state estate taxes will again be zero starting in 2011 as the full credit for state estate taxes will be in place again.

There are a variety of proposals to modify the path currently set in law. Until this debate comes to a conclusion, it is not possible to determine the impact of a state estate tax in 2010 and beyond.

Appendix

Provisions of the 2001 Federal Estate Tax Cut

The federal tax cut of 2001 made three major changes to the estate tax that affect the amount of federal and state taxes owed.

-

First, the law gradually lowers the top rate for federal taxes owed. In 2001, the top rate equaled 55 percent. By 2009, it will have declined to 45 percent. (See Appendix table 1.) In 2001, the federal top rate applied to the value of estates that exceeded $3 million. As the rate declines, the size of the estate subject to the top rate will also decline.

-

Second, the size of estates that are exempt from the federal tax is being increased. The exemption equaled $675,000 in 2001 and will increase in steps to $3.5 million by 2009. The exemption equals $1.5 million for 2005, and $2 million for 2006, 2007 and 2008.

The state credit was repealed on a much faster timeline than the repeal of the federal tax. The credit was phased out over four years and was eliminated for deaths that occur in 2005. Starting that year estates could deduct the amount of state and inheritance taxes from the value of their estate to determine the amount subject to the federal estate tax.

The effect of the repeal of the state credit is different depending on how the state is linked to federal law. In many states, the amount of the state estate tax is set to be equal to the amount of the credit that can be taken against federal taxes. So, the repeal of the credit effectively repealed those states’ estate taxes.

By contrast, some 17 states and the District of Columbia are not directly linked in this way.[6] (This is the result of legislation passed since the federal estate tax repeal passed or because of the way their estate tax laws are written.) These states will retain their estate tax in the amount of the credit as it stood in 2001 or a similar amount. Estates in these states can take a declining portion of the state tax as a credit against federal estate taxes owed. In 2003, that credit equaled 50 percent of the state taxes paid and in 2004 it equaled 25 percent. In 2005 and beyond estates can take a deduction against their federal estate taxes for the amount of the state tax.[7]

Click here to download additional appendix tables

End Notes:

[1] The estate tax in Virginia will expire effective July 2007, in Wisconsin in 2008 and in Kansas in 2010.

[2] A few states have adopted a different rate schedule but the amount of tax owed is very similar.

[3] Under 2001 law, estates received a dollar-for-dollar credit for state estate taxes paid up to a specified maximum. This credit was phased out effective 2005. Estates are now able to take a deduction for state estate taxes paid. That is, they can subtract the amount of state estate taxes paid from the value of the estate that is subject to federal taxes. The value of this deduction to the estate is the amount of the tax paid times the estate’s marginal tax rate. Under the new law the top marginal rate will equal 45 percent and will apply to the value of estates that exceeds $2 million. This deduction will reduce the cost of a state’s estate tax by the marginal rate times the amount owed to the state. So, an estate subject to the highest state rate of 16 percent will effectively be paying only 8.8 percent.

[4] The data from 2004 are the most recent available from the Internal Revenue Service. They provide a good estimate of the estates that could possibly be subject to state estate taxes in states that have decoupled from the federal estate tax cut and are using the federal exemption amounts. Other states have tied their estate tax to 2001 law. In 2001, about 2 percent of estates were subject to the federal tax. States that have decoupled will be taxing estates of the size that would have been subject to the federal tax in 2001 or have adopted higher exemptions, so the percent of estates subject to state taxes should be similar to or lower than the number subject to the federal tax in 2001.

[5] This example assumes that the state has adopted the increases in the federal unified credit that were part of the federal tax law of 2001. This assumption does not affect year 2002 through 2008. However, if the state has not adopted these increases an estate of $2.5 million will continue to owe state estate tax in 2009. The amount will equal $138,800 and will not be offset by a deduction against the federal tax as the estate will not owe federal tax.

[6] The estate tax in Virginia will expire effective July 2007, in Wisconsin in 2008 and in Kansas in 2010.

[7] It should be noted that for estates in states that have decoupled from the federal changes, the deductions allowed in 2005 and beyond will be worth more than the 25 percent credit allowed in 2004 because the top marginal rate is significantly higher — 47 percent in 2005, 46% in 2006 and 45 percent in 2007 and beyond. The value of the deduction is the amount of the state tax paid times the marginal tax rate. in 2006, for example, 47 percent — which results in a reduction in federal taxes owed that is almost twice as large as a 25 percent credit. |