TAX CREDITS FOR INDIVIDUALS TO BUY HEALTH INSURANCE

WON'T HELP MANY UNINSURED FAMILIES

by Iris

J. Lav and Joel Friedman

Overview

| View PDF version If you cannot access the file through the link, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

Although the majority of Americans under age 65 have health insurance, one in every six of the non-elderly — some 42 million people — are not insured. Recently, President Bush, various members of Congress, and some policy organizations have proposed addressing this problem through the creation of refundable tax credits with which individuals could purchase insurance.

Helping uninsured people obtain health coverage is an important goal and an appropriate use of public funds. Public funds devoted to this purpose should be used efficiently and effectively. Unfortunately, the research and evidence suggests that the type of individual tax credits now under discussion are unlikely to help many uninsured families obtain quality health care and could erode coverage for substantial numbers of currently insured families. Among the problems and shortcomings of the individual tax credit proposals now circulating are the following:

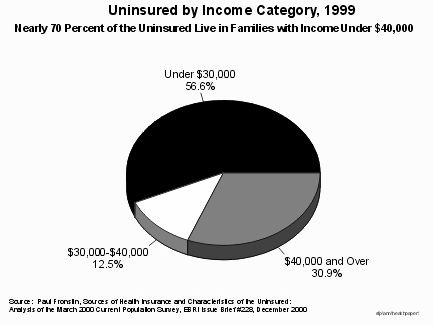

- The proposed tax credits are typically of inadequate size to make insurance affordable for the low- and moderate-income families that make up 70 percent of the uninsured population in the country. Health insurance is expensive. The average cost of group family insurance (purchased through employers) exceeds $6,000 a year, while mid-range premiums for family insurance in the non-group market exceed $7,000 a year. After applying the proposed tax credits — typically $2,000 to $2,500 for families — a family with income of $30,000 would still have to expend 10 to 15 percent or more of its gross income to purchase health insurance. Studies indicate that such expenditure levels are well beyond what most moderate-income families can afford.

- The tax credit proposals would impose few quality-control standards on the type of insurance that could be purchased with the credits. Some companies are likely to market policies with high deductibles and scant coverage that fit the size of the credit. Such policies generally would require families to spend several thousand dollars on health care before they receive any reimbursement from the insurance. Most of these families would receive little benefit from these policies, because they would have out-of-pocket medical expenses as high as they do today.

- The credits generally rely on people purchasing insurance in the individual, non-group insurance market, where older people and people with health problems generally cannot obtain insurance or can obtain insurance only at prohibitive costs. Health insurance in the non-group market is not only more expensive than comparable coverage in the group market (where employers purchase health insurance), but policy premiums vary widely depending on a person's age, gender, residence, and health status. Nearly half of the uninsured are not in very good health or are between the ages of 55 and 65, making it likely that many of them would face unaffordable premiums in the individual market or not be able to obtain insurance at all.

- The existence of an individual health insurance tax credit might lead a significant number of employers not to provide insurance coverage for their employees. To the extent that employers drop or fail to institute coverage as a result of their employees being able to secure an individual tax credit, the employees would be exposed to the vagaries and risks of the non-group market. Some families could end up with less coverage at higher costs.

- Some proposals allow individuals to choose to use their credit either for employer-based coverage or for privately purchased insurance; this would encourage "adverse selection" and increase the cost of employer-provided insurance. To the extent that adverse selection occurs — that is, to the extent that younger and healthier employees look for lower-cost coverage outside of employer plans, and employees with greater health needs become concentrated in the employer plans — the cost of insurance premiums for employer plans would rise and become less affordable. Increases in the cost of premiums due to adverse selection that are passed through to employees could mean that some employees would no longer be able to afford coverage. Higher premiums also could lead additional employers to drop coverage.

- Individual tax credits present a host of administrative problems, including the problems of the mismatch between the time that health insurance premiums must be paid and the time that the reimbursement is available through a tax credit. Low- and moderate-income families cannot afford to pay thousands of dollars for health insurance premiums during the year and then wait to be reimbursed when they file taxes in the following year. As described in detail below, all of the plans that seek to overcome this problem have major pitfalls.

The type of individual tax credits for purchase of health insurance that are currently being discussed represent a costly policy that is unlikely to result in adequate health coverage for most individuals and families that currently are uninsured. Other policies, such as expansions of public programs — perhaps coupled with other selected tax-based strategies such as employer tax credits — hold substantially greater promise for covering the uninsured.

Value of the Credit is Typically Too Low to Make Health Insurance Affordable

To be successful in substantially reducing the ranks of the uninsured, a program to cover the uninsured must make insurance affordable for the low- and moderate-income families that make up most of the uninsured population in the country. Nearly 60 percent of uninsured people live in families with incomes below $30,000, and about 70 percent live in families with incomes below $40,000. The individual tax credits that have been proposed are too small to make health insurance affordable for most of these families; research shows that perhaps only one-fifth of moderate-income uninsured families, and a still-smaller percentage of low-income families, would be able purchase insurance with credits of the size under consideration.

- Most of the tax credit proposals rely on people using their credit to purchase insurance in the individual, non-group market. (See below for more discussion of the non-group market.) Policies purchased in the individual market are expensive. The General Accounting Office identifies the "medium" cost of a non-group health insurance plan for a family of four as $7,352 per year.

- Many of the tax credit proposals would provide $1,000 for an individual and $2,000 for a family to offset the cost of health insurance. These are the levels proposed, for example, by President Bush in his campaign and in the Armey-Jeffords bill in the last Congress. (See Appendix A for a brief description of various proposals.) After applying a credit of this size, the remaining premiums for "medium" cost health insurance coverage for a family would be $5,352, absorbing 18 percent of the income of a family that earns $30,000.

- Even a credit as large as $3,600 for family coverage, such as the one proposed by Rep. Pete Stark, would reduce the cost of a "medium" family plan to $3,752. This lower cost still represents 12 percent of income for a family earning $30,000. (See Table 1.)

- Few low- and moderate-income families are likely to find room in their tight budgets to pay for health insurance if it still consumes 10 to 20 percent of gross income after applying the credit. A recent analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation concluded that only subsidies that pay nearly the full cost of insurance premiums will induce these families to purchase coverage.

| Income Level | |||

| $20,000 | $30,000 | ||

| Premium | Percent of Income | ||

| Premium with No Credit | $7,352 | 36.8% | 24.5% |

| Premium with $2,000 Credit | $5,352 | 26.8% | 17.8% |

| Premium with $3,600 Credit | $3,752 | 18.8% | 12.5% |

- The inadequacy of the tax credits under consideration will compound over time, as none of the proposed credits are adjusted in future years to take into account the effects of medical inflation. This year, for example, many insurers are projecting premium increases of 10 percent or more; insurance costs routinely grew at double-digit rates through the 1980s and into the early 1990s. Some of the credits make no adjustments whatsoever, while others are adjusted only for general inflation, which historically has been substantially lower than medical inflation.

Tax Credits Would Stimulate Low-Quality Health Insurance Policies

Some proponents of tax credits argue that some health insurance is better than no health insurance. Even if the amounts of the proposed credits would be inadequate to allow purchase of a more comprehensive policy, the argument goes, families would be able to use tax credits to purchase some type of insurance policy. Indeed, it is reasonable to expect that companies would develop and market policies that people could buy using the credit alone, without adding additional funds. Enactment of a credit for purchase of health insurance of $2,000 per family, for example, would likely result in family policies being offered for sale that cost about $2,000. Such insurance policies clearly would have limited benefits; the question is whether those benefits would be of significant value to families. The evidence suggests that these limited policies often would not provide families with meaningful coverage to address their health care needs.

A survey conducted by the authors through the Internet of low-cost insurance policies that are available to individuals and families in six U.S. cities suggests that the purchase of a policy that matches the value of the tax credit might not provide much improvement in a family's financial situation vis-a-vis the family's health costs. Family policies costing in the range of $2,000 to $2,500 — about the amount that would be covered by the proposed tax credits — carry high deductibles, high cost-sharing and narrow benefit coverage. In some of the plans, for instance, the deductible was $5,000 per family. That means a family with an income of $30,000 would have to spend a full one-sixth of its income on health costs before receiving any benefit from these policies. Other policies cover only inpatient hospital expenses — providing no reimbursements for outpatient procedures, office visits, maternity care, or medications — and require co-payments for covered services of as much as 50 percent. Most low- or moderate-income uninsured families would be little or no better off with such policies than they are today. (See Appendix B.)

- Experience with an individual health insurance credit for children that was part of the Earned Income Tax Credit in the early 1990s indicates that if a modest-sized health tax credit is established, insurance companies will indeed design, market, and sell cut-rate policies that offer limited benefits. A Congressional investigation of policies sold in response to the EITC child health insurance credit revealed that many policies paid only for costs up to an absurdly low limit (such as $50 per day for hospitalization) or covered only specific diseases (often diseases that rarely occur among children). The rise of these rather flimsy insurance policies, which often were marketed to unsuspecting low-income working families, prompted then-Treasury Secretary Lloyd Bentsen, the original lead supporter of the credit when he was in the Senate, to help push through its repeal after just three years.

- Furthermore, as a result of the establishment and growth of the State Children's Health Insurance Program, nearly all children from families with incomes below 200 percent of the poverty line — or about $35,000 for a family of four in 2000 — now are eligible for Medicaid or a SCHIP-funded program. In a growing number of states, the parents of these children are also eligible. Many of those who are eligible, however, have not yet enrolled and need to be reached. If aggressive marketing by private insurers in response to an individual health insurance tax credit encourages these families to use the credit to buy policies in the non-group market instead of enrolling in Medicaid or SCHIP, these families would receive much less in the way of comprehensive coverage than they could receive from the public programs for which they are eligible. The establishment of these credits thus could depress participation rates in Medicaid and SCHIP. The existence of the credits also could discourage state policymakers in some areas from expanding their Medicaid and SCHIP programs to serve more low-income working parents.

The Individual Market is Risky, and Credits Could Degrade Coverage for Older, Less Healthy Workers

Most of the proposed tax credits would subsidize health insurance purchased in the individual, non-group market, as opposed to the group market available to employers. Non-group insurance is more expensive than comparable group insurance, reflecting the high administrative costs associated with marketing and selling policies to individuals and the inability of non-group insurers to pool risk over a large group. Moreover, policy premiums in the individual market can vary widely, depending on a person's age, gender, health status, and geographic location. In some areas, non-group insurance is simply not available to people who need it, as insurers can deny coverage to applicants who have preexisting health conditions. In most states, the non-group market is weakly regulated.

- According to Commonwealth Fund estimates, nearly half of the uninsured are not in very good health or are between the ages of 55 and 65, making it likely that many of them would face unaffordable premiums in the individual market or not be able to obtain insurance at all.

- Some employers will use the credit as an opportunity to drop coverage or not to initiate it, leading their employees to seek insurance in the precarious non-group market. Workers who could not afford to buy coverage, even with the credit, or could not obtain insurance would end up uninsured.

- Some tax credit proposals attempt to address the problems of the individual market by suggesting that purchasing groups could be formed voluntarily or that states could regulate access to insurance in the individual market. This is likely to be considerably more difficult than some proponents of these proposals suggest. RAND Corporation economists Stephen Long and Susan Marquis surveyed research on the experience of states and found that those states that have tried such approaches have had only limited success in mitigating the problems of the non-group market.

- The problems posed by the non-group market could be bypassed only if use of an individual tax credit were limited to purchase of insurance through some large, well-established insurance pool. Rep. Pete Stark's proposal, for example, would allow a tax credit only for the purchase of qualified plans sold through a new federal Office of Health Insurance, which would offer plans from the same insurers selling insurance to federal workers through the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program. Many supporters of individual health tax credits hold strong ideological opposition, however, to such regulation. It seems highly unlikely that a tax credit that Congress might pass would include such regulations and protections.

Individual Tax Credits are Not Well Targeted on the Uninsured

Individual tax credits are an inefficient way to cover the uninsured. Tax credits for individuals tend to provide more subsidies to people who already have insurance than to the uninsured. Research indicates that most of the tax credit proposals would provide the bulk of their subsidies to individuals and families who already are purchasing insurance on the individual market, or to employees whose employers drop coverage as a result of the availability of the individual tax credit.

Professor Jonathan Gruber of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has conducted research that shows the extent to which individual tax credits would result in churning in health insurance coverage — that is, workers moving from employer coverage to individual coverage with a credit — rather than result in large numbers of previously uninsured individuals and families becoming insured. Gruber found that an individual tax credit that is similar to the credit in most of the major proposals being considered would have only a modest impact in reducing the number of uninsured, because three-quarters of those making use of the credit would already have health insurance — either through their job or purchased on their own.

- Gruber examined a credit of $1,000 for individuals and $2,000 for families, limited to people without access to employer-sponsored coverage. (This proposal is nearly identical to one offered by Majority Leader Richard Armey and Senator Jim Jeffords in the last session of Congress, and the one that President Bush presented during the campaign.) Gruber estimated that overall about 10 million people would use the credit, but that the number of uninsured people would fall by only 2.1 million. This poor targeting drives up the cost of tax credits per newly insured individual, rendering credits an inefficient way to extend coverage to the uninsured.

- Under such a credit, some employers would drop coverage for their employees, preferring that their employees use the tax credit instead of including health benefits as part of the employees' compensation. Gruber estimated that 4.1 million employees would be newly forced to buy insurance outside the workplace. He also estimated that about 600,000 of these workers would not be able to obtain insurance, even with the tax credit, and thus would become uninsured.

About 15 percent of all uninsured people — or six million people — live in families where the worker has declined employer-sponsored coverage. Surveys have shown that the most common reason for the uninsured to decline employer-based coverage available to them is that it is too expensive.

- Most proposals for individual tax credits cannot be used to pay the employee's share of employer-subsidized health insurance premiums and thus do not help employees who are uninsured because they cannot afford the insurance their employers offer.

- A few of the proposals, including proposals by Rep. Charles Norwood and the Progressive Policy Institute, do allow employees to use a smaller tax credit to help pay the employee share of employer-subsidized insurance. Such an approach could help some workers who are offered insurance by their employer but cannot afford to purchase it. In the PPI plan, only low- and moderate-income employees would be able to use the tax credit. If a provision to allow credits to be used for an employee's share of premiums were to be extended to most or all taxpayers who currently have employer-provided insurance rather than just to lower-income people, however, it becomes very costly and would be poorly targeted on the uninsured.

A tax credit that is available to everyone regardless of whether they are eligible for employer-offered insurance also has the potential to erode the existing employer-based system. For example, healthy employees who could get a better deal on the individual market would not have the option of leaving the employer plan if the credit were restricted to those whose employer does not offer insurance. Credits that are available regardless of the availability of employer coverage, however, could set off a spiral of "adverse selection" as young and healthy workers use the credit to buy non-group insurance at a lower cost than they pay for employer-sponsored coverage.

The Progressive Policy Institute Proposal A proposal by the Progressive Policy Institute attempts to grapple with some of the more problematic aspects of an individual tax credit. In particular, it attempts to develop a way to provide individual tax credits while avoiding some of the vagaries of the non-group insurance market. While a thoughtful effort, the PPI proposal still exhibits many of the pitfalls and problems of individual tax credits identified in this analysis. Moreover, the solution that it develops to mitigate non-group insurance problems relies on requiring all employers to offer and process (although not subsidize) insurance for their employees. It also mandates states to create insurance pools and products. Absent these requirements and mandates, which are not likely to be acceptable to smaller businesses and states and thus are unlikely to be approved by Congress, the PPI plan is quite similar to the other proposals discussed in this report. For taxpayers not covered by an employer-subsidized plan, the PPI tax credit would be $1,000 for individuals and $2,500 for families. A smaller credit would be available to employees using an employer-subsidized plan. (Note that PPI's explanation of its plan is unclear with respect to when employees would be eligible for the larger or the smaller credit. The proposal appears to say that a taxpayer who is eligible for an employer plan but prefers to purchase individually would get the larger credit.) Like the credits in most of the other plans currently under discussion, the PPI credit would not be large enough to make insurance affordable for the low- and moderate-income families that comprise most of the uninsured. Even if the PPI plan were successful in its intention to encourage group purchase and thereby hold down the cost of insurance as compared to the non-group market, the credit would make insurance affordable only for a modest fraction of the uninsured. The cost of family coverage averages $6,350 per year in the group market, of which $2,500 could be paid by the credit. That would leave a family earning $30,000 with the need to expend one-eighth of its gross income to purchase insurance. For most families at this income level, costs would remain prohibitive. The PPI plan tries to create access to group insurance for those who currently do not have such access. The proposal requires employers to offer insurance plans to their employees, either through employer-arranged group insurance or through special groups set up by states. The proposal also requires employers to determine which of their employees are eligible for the credit, based on family income. Furthermore, the proposal asks employers to advance to their eligible employees over the course of the year, in their paychecks, the amount of their anticipated credit. The advance payments are intended to alleviate the problem of moderate-income families being unable to afford to pay up-front for insurance and then wait for a refund a year later at tax-filing time. For the PPI plan actually to garner these advantages and be an improvement over tax credit plans that rely on the individual insurance market, however, legislation would have to be enacted requiring employers to perform all the mentioned functions: offer insurance plans, enroll their eligible employees, and provide advance payments of the credit through employees' paychecks. Nearly half of uninsured workers are employed by small businesses, which do not have a history indicating eagerness to take on these roles. Even if the employers were required to perform these roles, there may be barriers to their doing so. Determining which employees are eligible for a credit that is based on family income and providing advance payments are far more complicated matters than they employees' wages, not their employees' family income. Employers could ask their employees about family income at the beginning of the year, but the total family income of low- and moderate-income families often fluctuates considerably during a year due to changes in family situation, job losses or job changes, overtime pay, and a number of other variables. For example, a Census study shows that only one-third of people who were poor in a given month were poor for two full years. If an employee receives a credit in his paycheck during the year but finds at the end of the year that his income exceeds the maximum eligibility level for the credit, he would owe large payments to the government at tax time to repay the credit. There are major questions about how the IRS would recapture these overpayments, since many low- and moderate-income employees would not have the funds to repay the credit. Would employers be required to withhold and remit to the IRS additional amounts from employee paychecks in the subsequent year to repay the credit? Would the risk of owing a repayment deter employees from using the credit? Problems with predicting annual family income are a major reason that only one percent of EITC recipients take their credits as advanced payments, even though — in an attempt to avoid these problems — EITC advance payments cover no more that 60 percent of the EITC benefit for which a family is expected to qualify. These problems would be magnified with respect to a health insurance credit since, to be effective, a health credit would require advance payments to be widely used and — given the large gap between the credit and the cost of insurance — would probably require advancing 100 percent of the credit during the year. In addition, the PPI proposal imposes new mandates on states. Under the PPI plan, states would be required to create risk pools and purchasing groups that would help small businesses offer insurance. States have had limited success in this area, even though several have tried. A recent review of state purchasing alliances by the RAND Corporation, for example, concluded that these purchasing arrangements did not reduce the cost of insurance to the small businesses that used them or increase the percentage of employers that offered insurance although they did help the small employers offer a wider range of policies. States may be reluctant to accept new mandates in an area in which their previous efforts have been discouraging. The PPI plan relies on the premise that mandates on states to create purchasing groups will hold down costs and make insurance more affordable. Another aspect of the PPI plan, however, could drive up the cost of insurance. The PPI plan appears to allow employees to choose among health plans, including plans other than those offered by their employer, and still receive the full tax credit. (The details of how this would work are not clear in the PPI materials.) Thus, an individual employee might choose to take a plan offered by his employer, the state, or perhaps a plan offered on the non-group market, using the tax credit to help pay the premiums. This creates the potential for "adverse selection" by tempting younger and healthier employees to look for lower-cost coverage outside of the employer-offered plan, leaving older and less healthy employees in the employer plan. To the extent that older and less healthy employees become concentrated in the employer-offered plan while individuals with less need for health care choose other forms of insurance, the cost of premiums for insurance through the employer plan would rise and become less affordable for those most in need of insurance. Finally, the PPI plan is particularly problematic for families with children covered under Medicaid and SCHIP. Instead of expanding Medicaid and SCHIP to cover low-income working parents, the PPI plan would either cover such parents alone or lead parents to move their children from comprehensive SCHIP coverage to what would in most cases be less comprehensive and more expensive insurance purchased with the credit. Under either choice, the family would be less well off than if SCHIP were expanded so more states would use SCHIP funds to cover parents along with their children. Some 17 states already cover parents with incomes up to at least 100 percent of the poverty line under Medicaid and SCHIP, and several others are moving in that direction. To the extent that the PPI plan discourages future state expansions of this nature, it could be a step backwards. |

If a tax credit encouraged a significant number of younger, healthier workers to switch out of employer-based coverage, this would leave primarily the older, less healthy workers in the employer's insurance pool, resulting in higher average premiums for those who remain. As adverse selection drove up the costs of employer-provided insurance, over time less and less insurance would be provided through the group market by employers. This could raise the cost of health insurance generally, and expose even more people to the problems in the individual, non-group insurance market.

Credits Will Be Complex to Administer and Implement

There are many administrative complexities associated with individual tax credits, some of which would likely undermine the effectiveness of a credit.

- Low-income families on tight budgets would have difficulty paying health insurance premiums during the year and then waiting until the tax filing season in the following year to be reimbursed by a tax credit. To be effective in helping substantial numbers of low- and moderate-income families who make up the bulk of the uninsured in buying insurance, the credit must be available at the time that insurance premiums are due rather than at the end of the year when taxes are filed.

- In an attempt to overcome this timing problem, some of the tax credit proposals provide for "advance payment" of the credit, either through the employer or directly to the insurer. In plans in which eligibility for a credit is limited to taxpayers with incomes below a specified level, however, it is difficult to determine eligibility in advance. The incomes of low- and moderate-income families fluctuate during the course of a year due to changes in family situation, job losses or job changes, overtime pay, and a number of other variables. As a result, a taxpayer could receive an advance payment and purchase insurance but later finds that his income for the year makes him ineligible for a credit. Any advance payment of the credit would necessitate a reconciliation process at tax time so the IRS could recoup any such overpayments.

- Based on experience with advance payment of the Earned Income Tax Credit, this reconciliation process, and the fear of owing money to the IRS at tax time, would likely deter most families from using this option. To help guard against overpayments and reduce the chances of a family having to pay back money at the end of the year, EITC advance payments are limited to 60 percent of a family's anticipated EITC. Yet despite this protection, only one percent of EITC recipients take the credit in advance. Under the health credit, an advance of 100 percent of the credit, not 60 percent, would be needed to pay the insurance premiums, so the problem would be considerably more acute than under the EITC. Also, the EITC advance payment option and reconciliation process has turned out to be complex and error-prone. There is no reason to believe that would not be the case with a health credit as well.

- The Internal Revenue Service will have a difficult time administering these tax credits. Most of the major tax credit proposals would require the IRS to collect new information and undertake new oversight responsibilities. For instance, most of the major proposals restrict the use of the credit by workers who have access to employer-sponsored coverage. In some cases, these workers are not eligible for the credit; in other cases, they are eligible for a reduced credit. Similarly, some proposals place restrictions on the type of insurance plans that qualify for the credit. The IRS currently does not collect information on health coverage available to taxpayers. Nor does the IRS have expertise to carry out the necessary oversight responsibilities to determine whether health plans meet prescribed standards. Accurate collection of required information and determination of what constitutes insurance under the definitions of the tax credit law could be complicated and burdensome. It also would likely be a source of error and abuse, since insurance comes in myriad forms.

- The experience of the EITC children's health tax credit is instructive here as well. Although the law did include some standards for the insurance that could be purchased with the credit, once some insurers began marketing ineligible policies that they misleadingly characterized to families as qualifying for the credit, the IRS had difficulty enforcing the standards.

Building on Public Programs and Employer-Sponsored Insurance is a More Effective Way to Help the Uninsured

With the introduction of the State Children's Health Insurance Program in 1997, states have extended insurance coverage to a wider range of children and parents, moving beyond the exclusively poor population traditionally eligible for Medicaid. About 3 million children are now covered through programs supported with SCHIP funds. The total number of uninsured children in the United States fell by more than one million between 1998 and 1999, in part because of increased enrollment of low-income children in publicly funded programs. Census data show a large effect on low-income children above the poverty line.

While coverage for parents of eligible children is more limited, a growing number of states are expanding coverage for working parents. Research shows that when eligibility of low-income working parents is expanded, and children and parents can be covered together through a common policy, enrollment of eligible children increases substantially. Currently, 94 percent of uninsured low-income children are eligible for SCHIP. This strongly suggests that increasing funding for SCHIP to expand coverage to parents of eligible children would bring more of these eligible, but not yet enrolled, children into the program. As HHS Secretary Tommy Thompson said in his confirmation hearing, "You know, the biggest problem, CHIP does not allow the parents to get health insurance at the same time. And so without allowing parents to enroll into the SCHIP program, you are going to, I think prevent a lot of children from being enrolled and a lot of working poor not being able to." Expanding eligibility to parents of covered children, and possibly to other low-income uninsured adults, would be an effective and efficient next step.

- A recent report by the Council on Economic Advisers reviewed a range of studies and evidence and concluded that, compared to various tax proposals, providing health insurance through public programs is the most efficient way to assist low-income families obtain insurance coverage.

- Evidence from states shows that broad Medicaid/SCHIP expansions that include parents increases the enrollment of children and can reduce the number of uninsured, and with minimal displacement of employer-sponsored health coverage.

- Rather than building on the success of these state-led efforts, tax credits may undermine this progress. A number of states may react to a tax credit, particularly one targeted at low- and moderate-income workers, by slowing or even backtracking on expanding coverage under Medicaid and SCHIP.

As noted, individual tax credits rely on the individual, non-group market that has many problems that cannot be overcome without a level of regulation unlikely to be acceptable to many proponents of tax credits. Building on and expanding Medicaid and SCHIP avoids those problems.

For uninsured populations that would not be reached by a Medicaid/SCHIP expansion, tax credits to encourage employers to offer health insurance, perhaps limited to businesses with lower-wage workers or to small businesses, offer an approach that is less subject to the problems of an individual tax credit. An employer credit would build on the existing system of employer-sponsored insurance, with its advantages of risk pooling and lower prices. It would avoid a fundamental problem with most of the individual credit proposals, which require people to purchase insurance in the precarious non-group market where the older and less healthy, in particular, face higher prices and restricted availability of coverage.

An employer credit also could facilitate greater take-up by eligible low- and moderate-income families. It does not have the timing problems that individual credits have in getting the subsidy into the hands of cash-strapped families when they have to pay their insurance premiums. Advance payment schemes, which are unlikely to be effective based on experience with the EITC, are no longer needed when the employer is purchasing the coverage.

Employer credits also have some limitations. For example, employer credits — like individual credits — are relatively inefficient because they would give credits to employers that already provide insurance. Nevertheless, on balance employer credits are better policy than the individual credits under consideration.

Overall, expansions in public programs, perhaps coupled with an employer credit, offer a much greater chance of reducing the number of Americans without health insurance than do the individual credits being considered.

SOURCES

Broadus, Matthew and Leighton Ku, "Nearly 95 Percent of Low-Income Uninsured Children Now Are Eligible for Medicaid or SCHIP," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 6, 2000.

Center for Studying Health System Change, "Who Declines Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance and Is Uninsured?," CSHSC Issue Brief Number 22, October 1999.

Council on Economic Advisors, "Reaching the Uninsured: Alternative Approaches to Expanding Health Insurance Access," September 2000.

Duchon, Lisa, et. al., "Listening to Workers: Findings from the Commonwealth Fund 1999 National Survey of Workers' Health Insurance," The Commonwealth Fund, January 2000.

Feder, Judith, et. al., "The Difference Different Approaches Make: Comparing Proposals to Expand Health Insurance," The Kaiser Project on Incremental Health Reform, October 1999.

Fronstin, Paul, "Sources of Health Insurance and Characteristics of the Uninsured: Analysis of the March 2000 Current Population Survey," Employee Benefit Research Institute Issue Brief 228, December 2000.

Glied, Sherry A. "Challenges and Options for Increasing the Number of Americans with Health Insurance," The Commonwealth Fund, December 2000.

Gruber, Jonathan, "Tax Subsidies for Health Insurance: Evaluating the Costs and Benefits," NBER Working Paper W7553, January 2000.

Kahn III, Charles N. and Ronald F. Pollack, "Building a Consensus for Expanding Health Coverage," Health Affairs, January/February 2001.

Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust, "Employer Health Benefits: 2000 Annual Survey."

Ku, Leighton and Matthew Broaddus, The Importance of Family-Based Insurance Expansions: New Research Finding about State Health Reforms, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 5, 2000.

Lemieux, Jeff, David Kendall, and S. Robert Levine, "A Progressive Path Toward Universal Health Coverage," Progressive Policy Institute Policy Report, December 2000.

Long, Stephen H. and M. Susan Marquis, "Have Small-Group Insurance Purchasing Alliances Increased Coverage?" Health Affairs, January/February 2001.

Naifeh, Mary, "Dynamics of Economic Well-Being, Poverty 1993-94: Trap Door? Revolving Door? Or Both?" Current Population Reports P70-63, July 1998.

Subcommittee on Oversight of the Committee on Ways and Means, U.S. House of Representatives, "Report on Marketing Abuse and Administrative Problems Involving the Health Insurance Component of the Earned Income Tax Credit," June 1, 1993.

Thorpe, Kenneth E. and Curtis S. Florence, "Why are Workers Uninsured? Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance in 1997," Health Affairs, March/April 1999.

U.S. General Accounting Office, "Earned Income Tax Credit: Advance Payment Option Is Not Widely Known or Understood by the Public," GAO/GGD-92-26, February 1992.

U.S. General Accounting Office, "Private Health Insurance: Potential Tax Benefit of a Health Insurance Deduction Proposed in H.R. 2990," GAO/HEHS-00-104R, April 21, 2000.

Major Proposals:

Refundable Tax Credits for Individuals to Purchase Health Insurance

During the 106th Congress, several members introduced legislation to establish refundable tax credits for individuals to purchase health insurance. President Bush proposed a tax credit for health insurance during the campaign. (This tax credit was separate from the overall Bush tax cut package and is not considered part of that package). In addition, some policy and advocacy groups have developed various individual tax credit proposals. The chart below outlines the major legislative proposals introduced in the last session of Congress, as well as the plans developed by President Bush and the Progressive Policy Institute.(1) All these proposed tax credits are either fully or partially refundable, but they differ in other key areas. These areas are discussed below and presented in the chart on the pages that follow.

Maximum credit

: Most of the tax credit proposals establish flat-dollar credits, with separate credit amounts for individual and family coverage. Some of the proposals index these credit amounts to the overall Consumer Price Index, while others do not. None of these proposals index the credit amount to any measure of medical or health insurance inflation. Because health care costs rise at a faster rate than prices in the economy in general, the value of the health insurance credit — and the level of health care coverage they would finance — would almost certainly erode over time. The one exception in this area is the proposal put forth by Rep. Jim McDermott, which provides a credit equal to 30 percent of the cost of the health insurance premiums; because it is expressed as a percent of insurance costs, the amount of the credit would rise automatically with increases in health insurance costs.Eligibility: All of the credits would be available to individuals that do not have access to employer-sponsored health insurance. Some of the proposals also make the credit available to those that do have access to employer-sponsored insurance. Only the plans advanced by PPI and Rep. Norwood would allow a credit that could be used to pay for an employee's share of employer-sponsored insurance.

Income phase out: Many of the credits are available to individuals and families no matter what their income level. Four proposals limit use of the credit to people below a specified income level.

Advance payment option: Some of the proposals authorize advance payments of the credit during the year, either through the employer or directly to an insurer, in an attempt to address the mismatch between the time that health insurance premiums must be paid and the time that income taxes are filed. Plans that allow advance payments all appear to require reconciliation on the employee's tax return at the end of the year, with the IRS recapturing any overpayment of the credit.

Restrictions on health policies: Most proposals would allow credits to be used for any type of health insurance policy, other than long-term care insurance, dental, and other highly limited policies. These restrictions, however, are not the same as setting an acceptable minimum level of insurance that can be purchased with the credit. Only Rep. Stark's proposal includes standards of insurance.