A RESPONSE TO ARGUMENTS AGAINST

EXTENDING

THE TEMPORARY FEDERAL UNEMPLOYMENT BENEFITS PROGRAM

by

Wendell Primus and Jessica Goldberg

| PDF of this report |

| If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

On November 22, Congress adjourned without enacting legislation that would prevent the Temporary Extended Unemployment Compensation (TEUC) program — which was enacted in March of this year as a response to the weak labor market — from expiring on December 28. As a result, more than 800,000 unemployed workers will have their unemployment benefits terminated three days after Christmas. Furthermore, after that date, no new workers will receive TEUC benefits when their regular, state-funded unemployment benefits run out.

House Republicans, unlike their Republican counterparts in the Senate, resisted extending the program in its current form. The Senate passed bipartisan legislation that would have extended the program in full for three months, but the House declined to consider it. The House instead adopted legislation that would have extended only limited parts of the program and only for five weeks.

The House Leadership, and especially House Ways and Means Committee chairman Bill Thomas, have defended these actions by arguing in a memo, press release, and various statements that the current unemployment situation is not serious enough to warrant full extension of the program. This analysis examines that claim. The analysis finds the claim does not stand up well under scrutiny.

The Purpose of the TEUC Program

The TEUC program was established to provide assistance to unemployed workers who are unable to find new jobs before exhausting their regular, state-funded unemployment insurance benefits, as well as to stimulate the economy by injecting dollars directly into local communities. Similar programs were enacted during the economic downturns of the early 1980s and early 1990s. Recessions have a dual impact on workers: more people lose their jobs, and those who are unemployed tend to be out of work for longer durations than during more prosperous periods. Temporary federal unemployment insurance programs are designed to assist long-term unemployed workers who have exhausted their regular, state-funded unemployment benefits and have not yet found jobs.

Do Current Labor Market Conditions Indicate a Need for an Extension?

One of the principal arguments that the Ways and Means Committee has made in defense of its opposition to full extension of the TEUC program is that the October unemployment rate of 5.7 percent was below the unemployment rate of 6.4 percent in place in April 1994 when the previous temporary federal unemployment benefits program ended. This may have sounded persuasive at first blush and made a good sound-bite. However, the unemployment rate increased to 6.0 percent in November. Also, that argument overlooked the fact that even the October unemployment rate had failed to decline from the level at which it stood when the TEUC program was established in March in response to an obvious need. (The unemployment rate was 5.7 percent in March.) More important, the overall unemployment rate is not the key criterion that indicates whether temporary federal unemployment benefits continue to be needed, primarily because it includes unemployed workers who are in their first six months of unemployment and have no need for federal unemployment benefits (since they are receiving regular, state-funded unemployment benefits). Furthermore, the unemployment rate includes people who are newly entering or returning to the labor market, a group that generally does not qualify for unemployment benefits.[1]

The single best measure of the need or lack thereof for federal unemployment benefits is the number of people exhausting their regular unemployment benefits without finding work. These are the individuals whom federal unemployment benefits are designed to help. Since regular unemployment benefits typically last for 26 weeks, those who exhaust these benefits generally are long-term unemployed workers who have been out of work for more than half a year.

Once the data are examined on the number of workers who are exhausting their regular unemployment benefits without finding work, a clear picture emerges. The number of such workers is high and is still increasing. These data indicate a strong need for continuation of the TEUC program.

- The number of workers exhausting their regular unemployment benefits without finding work —the group of workers in need of federal unemployment assistance — has been significantly greater in every month of this year than in the same month of the previous year.

- Some 360,000 workers exhausted their regular unemployment benefits in October 2002 without finding work. That is more workers than exhausted regular unemployment benefits during any October of the economic slump of the early 1990s. (When the number of workers who exhausted benefits in the early 1990s is adjusted upward to reflect growth in the size of the labor force since that time, the number of workers exhausting regular unemployment insurance benefits in October 2002 is the same as the number who exhausted benefits in October 1991, which was the October during the previous recession in which the number of workers exhausting benefits was highest.[2])

- The percentage of unemployed workers exhausting their regular unemployment benefits before finding work has reached a record level and is continuing to rise. In October 2002, some 47 percent of the workers who began receiving regular unemployment benefits six months earlier (in March) ran out of these benefits without finding work. This percentage, known as the “exhaustion rate,” is the highest for any October on record. (These data go back to 1980. October 2002 is the latest month for which these data are available.) The high exhaustion rate for October is not an anomaly; the exhaustion rates for July, August, and September 2002 set record highs for those months as well. These data provide a further indication of the difficulties that many unemployed workers are facing in finding jobs.

When Should the Temporary Federal Program End?

In the past, federal unemployment benefits programs established during economic slumps have remained in place until the number of workers exhausting their regular benefits has declined substantially. The temporary federal unemployment benefits programs of the early 1980s and early 1990s did not end until the number of such workers had been falling for a considerable period of time. By the standards used in the economic slumps of the early 1980s and early 1990s, the TEUC program should be continued rather than ended.

-

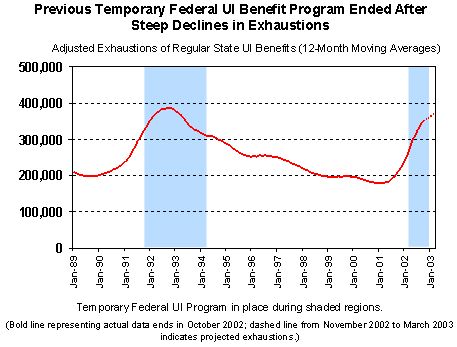

When the temporary federal unemployment benefits program of the early 1990s ended in April 1994, the average number of workers exhausting their regular unemployment benefits had been falling for 19 consecutive months.[4] (See graph at the top of the page. The numbers reflected in the graph are adjusted for changes in the size of the labor force. This has the effect of adjusting upward the numbers for the early 1990s.) When the temporary federal program ended after the recession of the 1980s, the average number of such workers had been declining for nearly two years. Today, the average number of such workers is still rising. The average number of workers exhausting their regular unemployment benefits has increased in every month since March 2001.

-

The temporary federal unemployment benefits program has lasted for far fewer months in the current slump than similar programs lasted in previous recessions. If the current program is allowed to terminate at the end of December, it will have been in existence for 9.5 months. The comparable programs lasted 29.5 months in the downturn of the early 1990s and 34 months in the early 1980s.

|

Can We Afford to Extend Federal Unemployment Benefits? The House Ways and Means Committee has argued that legislation the Senate passed in November to extend the TEUC program for three months is unaffordable because of its $4.8 billion cost. This argument overlooks three important points.

|

In contrast to the historical precedent of ending the federal temporary benefits program only after the number of workers exhausting benefits has fallen, Chairman Bill Thomas and the House Leadership have relied on the national unemployment rate to argue that the TEUC program does not need to be extended in all states. They have suggested that because October’s unemployment rate of 5.7 percent was lower than the unemployment rate of 6.4 percent when the temporary federal benefits program of the early 1990s ended in April 1994, there is no need to extend TEUC. As explained above, the unemployment rate is not the best criterion for determining whether the TEUC program should be extended. In addition, the increase in the unemployment rate to 6.0 percent in November indicates that this measure itself does not provide a convincing argument for ending TEUC, since the unemployment rate in November equaled the highest unemployment rate experienced at any time since the current economic slump began. The November unemployment rate also is consistent with the Congressional Budget Office’s projection that the unemployment rate will remain near 6.0 percent until the middle of 2003.

In past downturns, temporary federal unemployment benefit programs ended only after unemployment had receded substantially from the peak levels reached during the downturn. When the program in place during the slump of the early 1990s ended in 1994, the unemployment rate had been declining for 10 of the previous 12 months and had fallen 1.4 percentage points from its peak during that recession. This is a far cry from the situation today, when the unemployment rate is at its peak level to date for the current downturn.

Have Employment Conditions Improved Since the TEUC Program was Established?

Stated another way, for the TEUC program to be terminated, employment conditions should have improved significantly from what they were in March when the TEUC program was created. Such improvement is not evident.

- Labor market conditions are modestly worse today than when the TEUC program was established. The unemployment rate stood at 5.7 percent in March. It remained at 5.7 percent in October and climbed to 6.0 percent in November. It is now nearly two percentage points higher than the pre-recession unemployment rate of 4.3 percent.

- The number of jobs in the economy is essentially the same as it was in March.

Has the Increase in Unemployment Been Less Severe in the Current Downturn?

Finally, although it is sometimes assumed that the increase in unemployment has been markedly less severe during the current economic slump than in the downturn of the early 1990s, this is not the case.

- The impact of an economic slump can best be measured by the number of additional people who become unemployed. The number of workers who have lost their jobs in the 20 months since the current downturn began is nearly the same as the number who lost their jobs during the first 20 months of the downturn of the early 1990s. Unemployment has increased by 2.4 million workers since March 2001, when the current downturn began. In the previous recession, the number of unemployed workers increased by 2.5 million over the same number of months.

- Moreover, the increase in the number

of workers who have lost their jobs and qualify for unemployment insurance — a

measure that factors out new entrants and reentrants to the labor market — is

greater in this downturn than in the previous one. About one million

more workers are receiving regular unemployment benefits than when the current

downturn began 20 months ago. The same number of months into the 1990s

recession, the number of workers collecting regular unemployment benefits had

increased by 750,000. This means more workers typically covered by the

unemployment insurance system have become unemployed in the 20 months since

the current slump began than over a similar period in the last downturn. The

increase in the number of workers receiving unemployment insurance in the

first 20 months of the current slump continues to be larger than the increase

in the comparable period of the previous downturn even when adjustment is made

for the increase since the early 1990s in the size of the labor force.

Rather than Ending the Temporary Federal Program, TEUC Exhaustions Indicate a Need to Strengthen TEUC Benefits

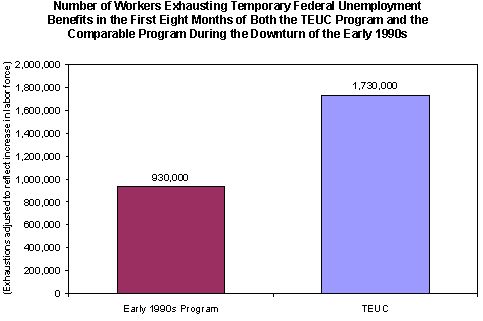

More jobless workers are exhausting their temporary federal benefits today than in the last downturn. The actual number of workers who have exhausted their temporary federal unemployment benefits since the TEUC program began in March is twice as large as the number who ran out of federal benefits over a comparable number of months in the downturn of the early 1990s. After adjusting for the increase in the size of the labor force, the number of workers who have exhausted their federal unemployment benefits since March remains more than 80 percent greater than the number who exhausted their federal benefits during the comparable period of the previous recession.

The number of workers exhausting federal unemployment benefits is higher than in the previous downturn in part because the current TEUC program is considerably more parsimonious than the program of the early 1990s was. In particular, the current program provides significantly fewer weeks of benefits. This suggests it would be useful to strengthen the current program by providing more weeks of assistance to those who have exhausted both their federal and state benefits and still not been able to find work.

End Notes:

[1] For the same reasons, the overall number of unemployed individuals also is not the best gauge of the need for temporary federal unemployment benefits.[2] Our adjustments reflect the following approach:

-

In October 2002, 360,000 jobless workers exhausted their regular unemployment benefits, as compared to the 300,000 jobless workers who exhausted their temporary federal benefits in October 1991.

-

The size of the labor force potentially affected by the unemployment insurance system has grown by 20 percent over the past 11 years. We increased the 300,000 figure for October 1991 by 20 percent to reflect this labor-force growth. That yields an “adjusted figure” for October 1991 of 360,000. After adjusting for changes in the size of the labor force since October 1991, the figures for October 1991 and October 2002 thus are equivalent.

[4] In measuring the number of workers exhausting benefits since March, we use a 12-month moving average. We do so because exhaustion data are not seasonally adjusted, and use of a 12-month moving average is the simplest way to analyze exhaustion trends while avoiding distortions caused by seasonal variations in employment.

Much as spending is best expressed in constant, or “real,” dollars, data in the graph are adjusted to reflect the growth in the labor force potentially affected by unemployment insurance since 1989. This permits comparisons of the number of workers exhausting benefits that are not affected by changes in the size of the labor force.