[*]SO-CALLED "PRICE INDEXING" PROPOSAL WOULD RESULT IN

DEEP REDUCTIONS OVER TIME IN SOCIAL SECURITY BENEFITS

by Robert Greenstein

Revised January 28, 2005 [*]SO-CALLED "PRICE INDEXING" PROPOSAL WOULD RESULT IN

DEEP REDUCTIONS OVER TIME IN SOCIAL SECURITY BENEFITS

by Robert Greenstein

| PDF of analysis |

|

| If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

Increasing attention is being accorded to a proposal to make a major change in how Social Security benefits levels are set. Under a proposal that President Bush’s Social Security Commission put forward in 2001, Social Security benefits would shrink dramatically over time as a share of workers' pre-retirement wages, replacing a much smaller share of pre-retirement wages for workers who retire farther into the future than for workers who retire sooner. The gap between Social Security benefits and pre-retirement wages thus would widen over time.

This proposal is sometimes referred to, in shorthand, as a proposal to change the Social Security benefit structure from “wage indexing” to “price indexing.” In reality, the proposal would maintain wage indexing, but would change the Social Security benefit formula by lowering the program’s “replacement rates” by the difference between wage growth and price growth. (The proposed change is explained on pages 4-5.)

This proposal is now in the news. In comments shortly after the election, President Bush said the plans that his Social Security Commission produced, the principal one of which includes this proposal, are a good place to start the debate.[1] On December 2, the chairman of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers, N. Gregory Mankiw, criticized “wage indexing” — the shorthand term used to describe the current approach — in a speech, while stating that “the Commission’s proposals [of which the proposal to lower replacement rates is a prominent part] are consistent with the President’s principles for reform.”[2] Most recently, White House Director of Strategic Initiatives, Peter Wehner, explicitly endorsed shifting to price indexing in a memo to Administration supporters that leaked in early January.[3] It also may be noted that a Social Security bill introduced last year by Senator Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), which essentially turns the principal Commission plan into legislation, includes this proposal; the Graham plan reportedly was developed with the help of White House staff. These developments strongly suggest that the proposal to change the Social Security benefit formula by lowering the replacement rates is receiving serious White House consideration.

The Effect on Social Security Benefits

Advocates of this proposal have sometimes sought to portray it as not representing a benefit reduction and as simply curbing excessive growth in Social Security benefits. But the change would, in fact, represent a substantial reduction in benefits, as compared to the benefits payable under the current benefit structure. According to estimates from the Social Security Administration’s Office of the Chief Actuary:[4]

Under the proposal, a worker born in 1977 who earned average wages throughout his or her career and retired at age 65 in 2042 would receive monthly Social Security benefits 26 percent lower than under the current benefit structure. Instead of this worker’s annual benefit being $19,423, the benefit would be $14,432, a $4,992 reduction. (These figures are in 2004 dollars)

The President’s Social Security Commission may have adopted this proposal in part because certain other Social Security benefit reductions are strongly opposed by large majorities of the population, such as increases in the age at which workers can retire and draw full Social Security benefits and reductions in the annual cost-of-living adjustment. During the Commission’s deliberations in 2001, some Commission members reportedly were attracted to the idea of “replacing wage indexing with price indexing” because this change would reduce Social Security benefit expenditures so substantially that other, better-understood, unpopular benefit cuts would not be needed.

|

It Is This Benefit

Cut, Not Individual Accounts, In recent weeks, the White House has sought to portray the notion of borrowing $2 trillion or so to fund individual accounts as the reason that the plan it is contemplating would eliminate the Social Security shortfall, which it has somewhat misleadingly described as totaling $10 trillion or $11 trillion. (The $11 trillion figure refers to an estimate of the shortfall not over 75 years but into eternity. Over 75 years, the shortfall is estimated by the Social Security Trustees to be $3.7 trillion, which amounts to 0.7 percent of the Gross Domestic Product over this period.) However, as numerous analysts have pointed out, the proposed borrowing of funds and the establishment of individual accounts would do nothing themselves to restore Social Security solvency. Under the main plan that the President’s Social Security Commission designed and that the White House now appears to be considering, it is the benefit cut produced by the proposal described in this report — i.e., the large reduction in the share of pre-retirement wages that Social Security benefits replace — that would eliminate the entire shortfall. This proposal would reduce Social Security benefits by more than the program’s entire $10 trillion to $11 trillion shortfall. White House Memo Admits Individual Accounts Would Do Nothing to Close the Shortfall In a White House memo to conservative allies that leaked in early January, Peter Wehner, the White House Director of Strategic Initiatives, acknowledged that individual accounts themselves would do nothing to close the projected Social Security shortfall and that the White House is looking to “price indexing” to close all of the shortfall. Wehner wrote: “If we borrow $1-2 trillion to cover transition costs for personal savings accounts and make no changes to wage indexing, we will have borrowed trillions and will still confront more than $10 trillion in unfunded liabilities.” Similarly in a December 17 analysis, the Wall Street investment firm Goldman Sachs told its clients that under the proposal the White House is likely to put forward, it is “the switch to price indexing from wage indexing that restores Social Security to solvency, not the implementation of a personal saving account system.” |

Some proponents of this approach have sought to present this change as providing a full inflation adjustment and therefore not constituting a benefit reduction. The Commission’s co-chairman presented this proposal as one that would merely “slow the rate of growth in future benefits,[5] and Commission reports contained a similar presentation. The Commission’s reports failed to explain that under this proposal, Social Security benefits would replace significantly less of pre-retirement earnings than they do today and that large reductions in benefits would result relative to the benefits that would be paid under the benefit formula now in law.

Many Social Security experts believe there are better and fairer ways to restore long-term solvency to Social Security than to adopt this harsh change.

Background: How the Current Benefit Formula Works

When a worker becomes eligible to receive Social Security benefits, his or her benefit level is determined through a two-stage process. In the first stage, the worker’s average monthly earnings are determined. This is done by taking the worker's annual earnings for each of the worker’s 35 highest earning years. The amount that the worker earned in each year before the worker turned 60 is then adjusted by the increase in the average wage level in the U.S. economy between the year in which the wages were earned and the year the worker reached 60 years of age. (Earnings after age 60 also are included but are not adjusted for increases in average wages.) This adjustment, known as “wage indexing,” is designed to ensure that the percentage of pre-retirement wages that Social Security replaces remains constant across generations.

The earnings levels for these 35 years are then averaged and divided by 12. The result is the worker’s “average indexed monthly earnings”

The second stage of the process is to apply the Social Security benefit formula to the worker's average monthly earnings. Under the formula, the Social Security benefit for an individual reaching the “full benefit age” (sometimes also called the “normal retirement age”), which is now 65 years and four months, equals:

(Workers can begin drawing Social Security benefits at age 62. If workers begin drawing benefits before they reach the full benefit age, however, their monthly benefit is reduced, in recognition of the fact that they will receive benefits for more years.)

The dollar amounts of $612 (at which the 90 percent benefit rate ends and the 32 percent rate begins in 2001) and $3,689 (at which the 32 percent rate ends and the 15 percent rate begins in 2001) are known as the program's “bend points.” The “bend points” are adjusted each year to reflect the change in average wages over the preceding 12 months.

A worker's Social Security benefit level is determined in this manner at the time that the worker retires. The worker’s benefit level is then adjusted in each succeeding year in accordance with the annual change in the Consumer Price Index. This assures that once an individual retires and starts to draw benefits, his or her benefit level will remain constant in purchasing power as the individual grows older.

The Proposed Change in the Benefit Formula

Under the Commission plan, the Social Security benefit formula would be changed, starting in 2009. The first stage of the benefit computation process (the calculation of a worker’s average indexed monthly earnings) would remain the same, but in the second stage of that process, the 90 percent, 32 percent, and 15 percent factors (i.e., the three bulleted items listed on the previous page) would each be multiplied by the ratio of the percentage change in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) over the preceding 12 months to the percentage change in average wages over the same period.

For example, if the Consumer Price Index rose three percent in a given 12-month period and average wages rose four percent, the ratio would be 1.03 divided by 1.04, or 0.99. This ratio of 0.99 would then be multiplied by the 90 percent, 32 percent, and 15 percent factors, reducing them to 89.1 percent, 31.7 percent, and 14.9 percent.

|

CPI Grows More Slowly Than Wages Wages generally rise

more rapidly than prices. The result is an increase over time in the

standard-of-living. For example, between 1988 and 2003, average wages

rose 76 percent while the Consumer Price Index rose 54 percent.*

|

In most years, use of this ratio would result in a fraction slightly less than one, since the increase in the CPI is generally smaller than the increase in average wages. What are now the 90 percent, 32 percent, and 15 percent factors would be multiplied by this fraction each year, which would steadily reduce these factors and thereby steadily reduce Social Security benefit levels. These factors would drop farther and farther over time.[6]

Impact on Social Security's Long-term Shortfall

In its

analysis of the Commission’s Model 2 plan, the Office of the Chief Actuary of

the Social Security Administration estimated that making this change in the

benefit formula would itself close the entire Social Security shortfall over

the next 75 years.[7]

Under the Congressional

In other words, this proposal would produce very large savings. It would do so because it constitutes a very large reduction in benefits, relative to the benefits payable under the current benefit structure.

Impact on Social Security Benefits

The magnitude of the benefit reductions that would occur can be seen by examining the changes in “replacement rates” that would result if this proposal were adopted. Under the current Social Security benefit formula, a steady average wage-earner who retires in future decades at age 65 will receive Social Security benefits that replace 36 percent of his or her pre-retirement earnings.[8] That is not an overly generous percentage. If the proposal to lower replacement rates (i.e., the proposal often described as changing from “wage indexing” to “price indexing”) is adopted, the proportion of wages that Social Security replaces will fall sharply.

These changes would mean that over time, the standard-of-living that Social Security benefits support for elderly retirees would decline markedly, relative to both the standard-of-living that the rest of society enjoys and the standard-of-living that workers themselves had before retiring.

Benefit Reductions Would Grow Over Time

As the above examples for 2042 and 2075 show, the benefit reductions would be greater for those who retire farther in the future than for those who retire sooner. A few more examples, with numbers taken directly from the analysis of the Commission plan issued by the Social Security Administration’s actuaries, illustrate the size of the benefit changes.

|

Impact of the Proposal |

||||

|

Year of Retirement |

Current-law Formula |

Proposal |

||

|

|

Benefit Cut |

Replacement Rate |

Benefit Cut |

Replacement Rate |

|

2042 |

— |

36% |

26% |

27% |

|

2075 |

— |

36% |

46% |

20% |

Now, suppose Mr. Conway had a son or daughter who also was a steady average wage-earner and who retired in 2075.

As these figures indicate, the proposal would result in a significant decline in the percentage of pre-retirement wages that Social Security benefits replace. As a result, future retirees would experience a larger decline in their standard-of-living when they retired than retirees experience today. Making this change in the Social Security benefit formula also would significantly reduce the standard-of-living that Social Security beneficiaries experience relative to the average standard-of-living of the rest of society. By themselves, Social Security benefit reductions of this magnitude would lead to higher levels of elderly poverty than would otherwise occur.

Under the

Commission’s Model 2 plan, people who chose to participate in individual

accounts would receive additional income in retirement from those accounts.

According to an analysis of the Model 2 plan by the Congressional

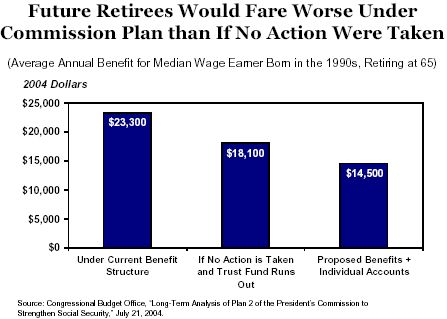

In fact, CBO estimates that the combined benefits would even be below the benefits that would be paid if policymakers took no action and Social Security benefits were reduced to the levels that Social Security revenues could support after the Social Security Trust Fund was exhausted. CBO estimates, for example, that workers born between 1990 and 2000 who earned median wages and retired at age 65 would receive combined benefits from Social Security and individual accounts that, on average, would be 20 percent below what would be paid if no action were taken to shore up Social Security’s finances (i.e., under a “do nothing” scenario).[9]

To be sure, under this proposal, benefit levels would keep pace with changes in prices. But Social Security beneficiaries would be precluded from partaking in the general increase in the standard-of-living that the society as a whole experiences from one generation to the next. Upon retiring, workers would essentially drop back to a standard-of-living prevalent in an earlier generation.

Impact on Survivors and People with Disabilities

The proposal would result in an across-the-board reduction in the benefits of all new beneficiaries, including people with disabilities and survivors. This is because Social Security uses a common benefit formula for all categories of beneficiaries, something that is necessary for reasons of equity. Changing the formula to lower Social Security’s replacement-rate factors over time consequently would affect all beneficiaries, not just retirees.[10]

The President’s Commission also proposed to improve Social Security benefits for elderly survivors by setting the benefit for a surviving spouse at 75 percent of what the couple would have received if both spouses were still alive. Under present law, a surviving spouse receives a benefit that equals 50 percent to 67 percent of the combined benefit the couple would have received. A similar proposal also is included in a number of other Social Security plans.

|

Various Analysts Across Political Spectrum Concur This Constitutes a Sharp Reduction Edward Gramlich, an eminent economist who chaired the Advisory Commission on Social Security in the mid-1990s and is now a Federal Reserve governor, recently noted, “If the system had not been wage indexed, [retirees] would be living today at 1940 living standards.”[11] Similarly, an earlier analysis of the Commission’s proposal said of the effects of the proposal: “This is like saying retirees who could afford indoor plumbing when they were working should, in retirement, not be able to afford indoor plumbing because their parents' generation could not afford it.”[12]

Some leading conservative proponents of replacing part

of Social Security with individual accounts have acknowledged this point.

For example, John Goodman, president of the

|

Combining this change with the proposed reduction in replacement rates, however, alters the impact. Because of the reduction in replacement rates, the combined benefit that a retired couple would receive in future decades would be significantly lower than what the couple's benefit would be under current law. As a consequence, the proposal to set the survivor's benefit at 75 percent of the couple's benefit would place the survivors benefit at 75 percent of a smaller amount. For many survivors, a benefit that is 75 percent of a substantially reduced amount would result in a lower guaranteed Social Security benefit than these survivors would receive under the current benefit structure. Overall, many elderly widows would receive lower — rather than higher — Social Security benefits.

The President’s executive order establishing the Commission charged that body with preserving the disability and survivors components of the program. The executive order did not preclude reducing benefits for new beneficiaries in these components of the Social Security program. Lowering the program’s replacement rates over time would substantially reduce the benefits of disabled workers and survivors. These are two groups that can ill afford to have their incomes diminished.

Moreover, a reduction in replacement rates instituted as part of a partial privatization plan could adversely affect disabled and survivor beneficiaries to a greater degree than retirees, because workers who become disabled or die at a young age will not have had the opportunity to build up much in their individual accounts before they are compelled to leave the work force due to disability or death. As a result, less income would be available from their individual accounts to supplement their reduced Social Security benefits.

Are Benefit Reductions of this Magnitude Necessary?

The Commission’s proposal to reduce the Social Security replacement rates apparently was influenced by several factors. The President’s charge to the Commission ruled out any changes that would boost payroll tax revenue. In addition, the Commission was unwilling to consider approaches that would scale back the large tax cut enacted in 2001 and dedicate some of the preserved revenue to Social Security, as could be accomplished, for example, if the estate tax were retained in a scaled-back form and the revenue from a smaller estate tax were dedicated to Social Security. Finally, diverting a portion of Social Security payroll tax revenues to individual accounts, as the Commission proposed to do, would make Social Security's funding gap larger and thereby necessitate deeper Social Security benefit reductions. These constraints appear to be part of the reason that the Commission proposed the reduction in replacement rates, despite the fact that it would constitute a large reduction in future Social Security benefit levels.[14]

The constraints under which the Commission operated, however, are not written in stone. Different approaches can be considered.

Suppose, for example, that the estate tax parameters that will be in place in 2009 were made permanent and the estate tax revenue collected was dedicated to Social Security.[15] Under this approach, estates worth less than $3.5 million for an individual and $7 million for a couple would be entirely exempt from the tax. As a result, the estates of 99.7 percent of Americans who died would face no federal estate tax whatsoever. Moreover, those few estates that would continue to owe estate tax would receive large reductions in the amount of tax owed compared to the amounts those estates would have owed under the law in effect before the 2001 tax cut. Yet the estate tax revenue that would still be collected would eliminate about 25 percent of the 75-year Social Security shortfall, as projected by the Social Security Trustees, and close to half of the long-term shortfall as projected by CBO.

This proposal to retain the estate tax in scaled-back form and dedicate the revenues to Social Security is one of the elements of a plan to restore long-term Social Security solvency recently designed by Robert Ball, who served as the Social Security Commissioner under Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon and helped design the 1983 Social Security legislation as a member of the Greenspan Commission that year. The Ball plan has been turned into legislation and introduced by Rep. David Obey. The Ball plan would restore long-term solvency to Social Security without benefit cuts of anything near the severity of the reductions that would result from the proposed reduction in replacement rates.

Similarly, a plan designed last year by economist Peter Diamond of M.I.T, one of the world’s leading experts on retirement systems, and Peter Orszag of the Brookings Institution would restore long-term solvency without benefit cuts of such harshness. An earlier Social Security plan designed by economists Robert Reischauer, the former CBO director who now is president of the Urban Institute, and Henry Aaron of Brookings also would restore solvency without benefit reductions of this severity.

As those plans indicate, restoring long-term solvency to the Social Security system does not require cutting the program’s replacement rates sharply over time and ultimately reducing guaranteed Social Security benefits by more than 45 percent. Restoring solvency does not necessitate instituting a system under which guaranteed Social Security benefits ultimately replace only about one-fifth of wages for average wage earners.

Conclusion

A Social Security proposal that the White House is considering, which is often referred to as replacing wage indexing with price indexing, would lead to large reductions over time in the percentage of workers’ pre-retirement wages that Social Security benefits replace. The proposal would constitute an across-the-board reduction in benefits that would affect all beneficiaries, including people with disabilities and survivors.

This proposal is not readily understood by the public and is complicated to explain. That may be one of its attractions to those who support it. It can be presented in a manner that sounds highly technical and does not make apparent the magnitude of the benefit reductions that will occur if the proposal is adopted. Yet enactment of this proposal would represent a very large change. The public should understand what the proposal entails and that there are alternatives to restoring Social Security solvency that do not require reductions of this magnitude in Social Security benefits.

End Notes:

[*] This analysis is adopted from Kilolo Kijakazi and Robert Greenstein, “Replacing ‘Wage Indexing’ With ‘Price Indexing’ Would Result in Deep Reductions Over Time in Social Security Benefits,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 2001.

[1]

President Bush’s news conference,

[2]

Text of remarks of N. Gregory Mankiw to conference sponsored by the

American Enterprise Institute,

[3] Peter Wehner, “Some Thoughts on Social Security,” available at http://online.wsj.com/article_email/0,,SB110496995612018199-Ihjg4Nhlah4m5uma3uGaayGm4,00.html.

[4] See Office of the Chief Actuary, Social Security Administration, “Estimated Financial Effects for Three Models Developed by the President’s Commission to Strengthen Social Security,” January 31, 2002, page 75. The estimate of the “% basic change for all” for the medium and high earners reflects the change from wage indexing to price indexing. All estimates are based on the 2001 Social Security trustees report. These benefit reduction figures assume this change would be instituted starting in 2009, as the President’s Commission proposed.

[5]

Statement of Richard Parsons, Commission co-chair, at Commission press

conference,

[6] The effect of this change is not the same as changing computation of a worker’s average indexed monthly earnings by substituting price indexing for wage indexing.

[7] See Office of the Chief Actuary, Social Security Administration, “Estimated Financial Effects for Three Models Developed by the President’s Commission to Strengthen Social Security,” January 31, 2002. This memorandum shows that the benefit changes in Commission Plan 2 would save 1.87 percent of payroll over the next 75 years (see page 37). Switching from wage indexing to price indexing would save slightly more than this amount because the 1.87 percent-of-payroll estimate includes the costs of some other relatively minor changes in benefits. This savings exceeds the 1.86 percent of payroll deficit estimated in the 2001 Social Security Trustees report.

[8] The replacement rate for an average wage-earner retiring at age 65 is currently 42 percent. The “full benefit age” (sometimes also called the “normal retirement age,” this is the age at which a worker may retire and receive the full Social Security benefit for which he or she qualifies) is scheduled to rise gradually over the next couple of decades to 67. As the full benefit age rises to 67, the replacement rate for a worker who retires at age 65 will edge down to 36 percent. It will then remain at this level.

[9]

Congressional Budget Office, “Long-Term Analysis of Plan 2 of the

President’s Commission to Strengthen Social Security,”

[10] The Social Security actuaries’ analysis of the Commission’s Model 2 plan notes, “this change applies to disability and survivor benefit cases, as well as to retirement cases.” The Commission also stated in its final report that “the calculations carried out for the commission and included in this report assume that defined benefits will be changed in similar ways for the two programs [i.e., Social Security’s Old Age and Survivors’ Insurance program and Social Security’s Disability Insurance program].” Commission presentations which showed that the Model 2 plan would restore Social Security solvency relied upon the savings from applying price indexing to all parts of Social Security. (The Commission did include a sentence in its final report stating that the application of this proposal to Social Security disability benefits in the Commission’s analysis of how its plan would restore solvency “should not be taken as a Commission recommendation for policy implementation,” but the Commission offered no specific proposal to shield disability benefits from this benefit cut. Doing so would be very difficult.)

It also may be noted that people with disabilities receive benefits from all of the programs within the Social Security system, not just the Disability Insurance program. For example, a child with a disability who remains disabled as an adult (known in Social Security parlance as “a disabled adult child”) receives Social Security retirement benefits when the child's parent retires. When the parent dies, the adult disabled child receives Social Security survivors benefits. Similarly, surviving spouses who are disabled receive survivors benefits. In addition, disabled workers who receive disability insurance benefits are switched to Social Security retirement benefits when they reach the “normal retirement age.” (Their benefit levels do not change.) As a result, reductions in any of these types of Social Security benefits would result in benefit reductions for some people with disabilities (unless complex changes are made in the Social Security benefit structure that would result in significant inequities in the benefit structure.)

[11]

Gramlich as cited in Greg Ip, “Social Security: Five Burning Questions,”

Wall Street Journal Online,

[12] “Price-Indexing the Social Security Benefit Formula Is a Substantial Benefit Cut,” prepared by the minority staff of the Social Security Subcommittee, House Committee on Ways and Means, November 30, 2001.

[13]

Cited in Edmund L. Andrews, “Most G.O.P. Plans to Remake Social Security

Involve Deep Cuts to Tomorrow’s Retirees,”

[14] Still another constraint was the President's charge to the Commission ruling out investing a portion of the Social Security Trust Fund's revenues in assets that provide higher average returns over time, such as equities. As analyses by the Social Security actuaries have shown, investing a portion of Trust Fund reserves in higher-yielding assets closes some of the long-term Social Security financing shortfall and reduces the magnitude of the changes needed in the Social Security benefit-and-tax structure to restore long-term solvency.

[15]