QUARTERLY

STATUS REPORTING COULD JEOPARDIZE

THE HEALTH COVERAGE OF HUNDREDS OF THOUSANDS OF

ELIGIBLE LOW-INCOME CALIFORNIANS

by

Donna Cohen Ross and Leighton Ku

| PDF of this report |

| If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

As states wrestle with ways to address their serious budget shortfalls, much attention has focused on strategies to curtail Medicaid spending. Some of the proposals that have surfaced seek to limit Medicaid caseloads by imposing complicated procedures families must navigate in order to obtain and retain health coverage. The idea of using one such strategy — Quarterly Status Reporting (QSR) — has been raised in California. As the state’s budget for state fiscal year 2003 was developed, one option proposed was to use QSR to reduce participation in Medi-Cal (the state’s Medicaid program), but this was not included as part of the final budget accord. Because new fiscal data indicate the state’s budget is continuing to falter, Governor Davis has called a special session of the legislature which convened on December 9 to consider further adjustments to the state budget. The Governor’s mid-year spending reduction proposals, released late last week, once again propose using quarterly reporting to lower enrollment in Medi-Cal and thereby to reduce expenditures.[1]

Under QSR, families participating in Medi-Cal would be required to submit paperwork four times a year as a condition of retaining their health coverage. Quarterly reporting in Medi-Cal was required in the past, but was eliminated in January 2001 in favor of a simpler system which requires families to submit reports only when their circumstances have changed.Studies show that excessive reporting requirements pose significant problems for beneficiaries. Many lose coverage — even though they still qualify — because they are unable to complete complicated forms, because mail delivery is unreliable or because overloaded administrative systems fail to process the paperwork correctly. Thus, the reinstatement of QSR achieves cost-savings by erecting barriers to participation for eligible individuals who would be cut from the program and, as a result, become uninsured. The California Department of Human Services has estimated that 193,000 people — a large proportion of whom are working parents — would lose their Medi-Cal coverage by June 2004 because of QSR.

This brief report discusses why the reinstatement of quarterly reporting in Medi-Cal could have serious negative ramifications for many of California's neediest parents and might have other unanticipated consequences, such as causing eligible children to lose health coverage.

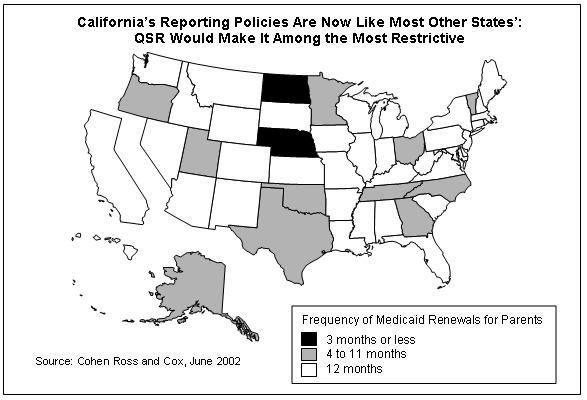

- QSR goes against the national trend. Across the country, the overwhelming trend has been for states to move away from procedures like quarterly reporting in Medicaid to relieve themselves and families of unnecessary administrative burdens and eliminate obstacles that cause eligible people from losing benefits and becoming uninsured. Currently, the reporting policies for parents in most states' Medicaid programs (38 states) are like those now in place in California. If California were to reinstate quarterly reporting, it would join the two states — Nebraska and North Dakota — with the most restrictive procedures. Nebraska requires families to renew their coverage every three months; North Dakota requires families to submit reports every month to retain their coverage.

- QSR imposes unnecessary administrative burdens. QSR would cause a large number of parents with incomes below the federal poverty line — the great majority of whom are employed — to lose coverage unnecessarily, simply because their paperwork was not processed on time. Studies have documented that administrative complications and other barriers are major reasons families are dropped from health coverage. Families at particular risk of encountering such problems are those with limited education, those who do not read or speak English, and those who do not receive the paperwork, such as homeless or migrant families.

- Individuals hurt by QSR are eligible for coverage. Almost all of those who might lose coverage under QSR are actually eligible for Medi-Cal. When families’ incomes rise, they are still eligible for Medi-Cal under transitional medical assistance. Transitional medical assistance was designed to ensure that low-income families shifting from welfare to work, or whose earnings increase, can retain their health insurance coverage. However, if families are unable to submit their QSR paperwork on time, it is not clear whether the state will let them receive transitional benefits, even though they are still eligible for coverage.

-

QSR jeopardizes children's coverage. While children on Medi-Cal are supposed to be guaranteed 12 months of continuous eligibility, many children could bear the brunt of confusing reporting procedures. For example, unintended computer errors could improperly terminate coverage for a child when her parent's coverage is terminated. One recent study found a high incidence of such "preventable administrative actions." In addition, a growing body of research suggests that providing health coverage to low-income parents helps boost the enrollment of eligible children and increases the likelihood that they will receive well-child care. Thus, if quarterly reporting is reinstated, the number of uninsured children in California could rise substantially and their health status could be compromised.

-

QSR could adversely affect California's health care system. QSR could harm the financial stability of health care providers in California. Safety net hospitals would have to treat more uninsured patients and would lose the Medi-Cal revenues they now receive to care for them. These problems could be the most severe in Los Angeles County, which is already experiencing great difficulties. Moreover, the reinstatement of QSR would place the county's federal waiver funding at risk because the federal terms for the waiver stipulated that reporting must be simplified. Finally, QSR could cause problems for Medi-Cal managed care plans, which in turn could create further financial pressure for health care providers.

Most States Have Policies That Promote Enrollment for a Full Year

Recent concerns about eligible low-income families losing health coverage have prompted states to take significant steps to streamline the Medicaid renewal process to improve retention and to simplify program administration. While major efforts have focused on simplifying the renewal process in children's health coverage programs, increasingly, the techniques used to facilitate renewal for children are being adopted for family coverage programs, as well. The overwhelming trend is for states to adopt strategies to reduce reporting requirements and the frequency with which families are asked to renew their coverage. Most states, including California, have moved to a system that requires families to renew their coverage annually and report changes if their circumstances have altered since they applied, such as if the parent gets a new job or if the family moves. California eliminated QSR in January 2001 to simplify the process and improve retention of coverage. In fact, a federal review of Medi-Cal operations expressed concern that a large number of beneficiaries were losing coverage because forms were not being returned. The state responded by noting that it was eliminating QSR to help families retain coverage for a year.[2]Reinstating QSR would cause California to drop back among the most restrictive states in the country, making Medi-Cal more complicated for both participating families and administrative staff. A Center on Budget and Policy Priorities survey of states' health coverage enrollment and renewal procedures, conducted for the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured,[3] found that as of January 2002:

- Thirty-eight (38) states — including California — allow parents to renew their health coverage every 12 months. Parents must report changes in family income or other circumstances that occur in the interim, but if no changes have occurred, the parent can retain coverage for the full 12 months without submitting any paperwork.

-

Only two states require parents to renew their coverage every three months or more often. In Nebraska, parents must renew their coverage every three months. In North Dakota, parents are subject to a monthly reporting requirement.

-

The remaining 11 states are in the middle. In Alaska, Georgia, Minnesota ("regular" Medicaid), North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas and Vermont, parents are required to renew their coverage every six months. In Utah, parents may be required to renew their coverage every four to six months if their income fluctuates. If their income is routinely stable, they are allowed to renew coverage every 12 months.

Almost All of Those Who Might Lose Coverage Under QSR Are Eligible

Proponents of quarterly reporting worry that a substantial number of families receiving Medi-Cal may become ineligible over the course of a year and believe a more vigorous review process is needed to remove them from the program. Such a belief, however, is misguided; almost all families that might lose coverage due to QSR when required paperwork is not received or processed by the county on time would still be eligible for Medi-Cal. Most of those affected are families that remain poor but do not make it through the complicated administrative barriers and therefore, would lose coverage. A smaller number of families would experience increases in their income during the year, usually because their earnings rise. Those whose incomes have climbed above the levels permitted for "Section 1931 eligibility" — the Medi-Cal eligibility category for which quarterly reporting would be imposed — would still be eligible for up to one year of additional coverage under transitional medical assistance (TMA), as required by federal law.[4] (The program is called Transitional Medi-Cal, or TMC, in California. In addition to the year of transitional coverage working families can get under federal law, California provides an additional year, for a total of two years of transitional coverage.)

Transitional medical assistance is an important component of federal and state health and welfare policy designed to encourage poor families to move from welfare to work or to seek better jobs, without fear that they will lose their health insurance coverage.[5] Cutting off the health coverage of families that increase their earnings discourages poor families from trying to work to improve their lives and the lives of their children. Under QSR, if these families report their increased earnings, they would gain continued coverage under transitional medical assistance. If they have difficulty with the administrative requirements and their quarterly report is not received or processed, however, they would lose Medi-Cal coverage altogether, even though they are still eligible.

Medi-Cal already has other systems in place that protect the program's integrity in a more efficient and less intrusive fashion. First, enrollees are required to report any changes in income and other circumstances within ten days. In addition, eligibility offices can and do monitor changes in beneficiaries' earnings using the state's automated wage reporting system. When the system indicates a change has occurred, the county office can contact the family to request additional information that may be needed. This system serves as a way to track changes in income even if reports are not received and serves as a "double check" to assess continued eligibility.

Excessive Paperwork Requirements Cause Eligible Families to Lose Coverage

Excessive paperwork requirements cause people to lose their insurance by creating confusing and unnecessary administrative barriers. Studies have documented that major reasons that families do not submit renewal reports are administrative complications and other barriers, not because they are ineligible. Common problems include not understanding they must renew their coverage, language and literacy barriers, and unreliable mail delivery. A recent study conducted by the National Academy of State Health Policy (NASHP) found that half the families of children whose SCHIP coverage had lapsed reported that they had not been told or did not recall being told that they would have to renew their child's coverage. The NASHP study also found that 44 percent of families whose children's coverage had lapsed said the documents required for renewal were too difficult to obtain.[6] Another study of disenrollment from SCHIP by the Child Health Insurance Research Initiative (CHIRI) found that the administrative requirements imposed by states for renewal lead a large share of children to be dropped from coverage.[7] However, up to one quarter of disenrolled children return to the program within two months, strongly suggesting that they were likely to have still been eligible for coverage at the point of disenrollment. (Many of the children in families that did not attempt to re-enroll are likely to have remained eligible, as well. These families may not have realized their children could still qualify or they may have been discouraged by the complexity of the procedures.) The CHIRI study also found that requiring eligibility redetermination every six months rather than every 12 months is accompanied by higher disenrollment levels over time.

QSR Could Jeopardize Children's Coverage

While only low-income parents are supposed to be affected by QSR, quarterly reporting is likely to have a negative, unintended effect on the ability of eligible children to retain their health coverage. California has established a policy to guarantee continuous coverage of children for 12 months regardless of changes in family income and other circumstances. A major advantage of this approach is that it assures that children — especially those with ongoing medical conditions — do not experience disruptions in care. It also makes the process simpler for both families and eligibility staff.QSR is not supposed to override this protection for children's coverage. Yet, many children, particularly those with the lowest incomes, apply for Medi-Cal coverage with their parents as a family unit, and if families — and county Medi-Cal agencies — are required to follow different procedures to retain health coverage for all members of the family, there is a serious risk that eligible children could lose coverage.

If California reintroduces a quarterly reporting requirement for parents, children are in danger of losing coverage if their parent is dropped from the program for administrative reasons.Unless county computer systems are modified to distinguish between family members who are subject to quarterly reporting and family members who are not, children could lose their coverage inappropriately. Such concerns are well-founded: an earlier federal review of the implementation of Medi-Cal for Section 1931 families found numerous examples of inconsistencies in operations across the counties and shortcomings in Medi-Cal computer systems.[8] Another risk is that children may not get the health services for which they are eligible because their parent may be confused about their insurance status. For example, when a parent receives a notice terminating her Medi-Cal coverage, she may mistakenly assume that because the family applied for coverage together, her children's coverage is cut off as well. This may lead her to delay or avoid seeking needed care because of concerns about the potential cost.

In other states, children whose coverage is supposed to be protected by 12-month continuous eligibility are not immune to the effects of administrative errors. For example, the CHIRI study cited earlier found that in Kansas, 36 percent of children were disenrolled prior to their renewal date, even though the state has adopted a 12-month continuous eligibility policy. Although some children were disenrolled for reasons such as moving out of state or reaching the program's age limit, Kansas officials indicated that a significant number lost coverage due to "preventable administrative actions." The researchers state that disenrollments of this type are likely to be followed quickly by re-enrollments for many children, which add to administrative costs.[9] The changes that California is contemplating can clearly lead to similar problems.When families are responsible for submitting reports if their circumstances change, as is now the case, there is an opportunity to review the eligibility of each member of the family based on the report. The opportunity for such a deliberate review protects those eligible for transitional medical assistance, discussed earlier, as well as children who are guaranteed 12 months of coverage. If a case is to be closed automatically when a mandatory quarterly report is not received by a certain date, there is greater risk that all members of the household could have their coverage terminated.

It would be unrealistic for another reason, as well, to assume that policy changes affecting the insurance coverage of parents can be implemented without also affecting children's coverage. Earlier research has shown that there are linkages between the coverage of parents and their children and that efforts that increase the enrollment of parents also lead to higher enrollment of eligible children.[10] In addition, other studies have found that children whose parents are uninsured are less likely to use health services, including preventive health services.[11] Thus, adopting harsher policies aimed at parents is likely to lead fewer children to apply for or retain coverage, and many of the children who remain covered might use health services less effectively.

Budgetary Savings for State Fiscal Year 2003 Will Be Slight

The new budget documents released by the Department of Finance indicate that reinstating QSR would save only $5 million in general funds in the 2002-2003 fiscal year, assuming implementation by April 1, 2003. The Department estimates $85 million in general fund savings in the 2003-2004 fiscal year. Implementation of a procedural change like QSR, however, requires developing new program guidance, training state and county staff, notifying beneficiaries and reprogramming computer systems. Given the administrative budget and staffing reductions that have already occurred in state and county offices, it may be difficult to implement the changes this quickly. Moreover, QSR would increase the administrative workload of the hard-pressed eligibility offices and it is not clear whether the budget proposal includes funding to augment administrative funds to account for the additional workload.

QSR Could Strain California's Health Care System

Reinstating QSR could also have serious consequences for California's health care system. Because the federal government matches state dollars in Medi-Cal, it is important to remember that a $90 million reduction in state spending leads to a reduction of $180 million in total funds available for health services in the state.Many families and individuals who lose Medi-Cal coverage because of QSR will turn to public and non-public safety net providers for care, creating further strain among safety net hospitals and clinics in California. The state has a broad array of state- and locally funded facilities and while limiting insurance coverage would decrease costs in the Medi-Cal budget, it would increase costs for these facilities.

The effects could be particularly grave in Los Angeles County, which already is in the midst of major financial problems that threaten its publicly-funded health clinics and hospitals and has resulted in the closure of half of the counties’ health clinics already. Los Angeles county has yet another serious concern. Under the federal terms and conditions for the county's Medicaid waiver, it was stipulated that quarterly reporting (which was in place at the time the terms were established) would be eliminated. The reinstatement of QSR might invalidate the waiver, placing some $400 million in funds for the remaining years of the waiver at risk and further deepening Los Angeles County's budgetary troubles.QSR could also create problems in Medi-Cal managed care. This is because people are more likely to join Medi-Cal when they need to see a doctor or have medical problems. After their immediate medical needs have been met, the ongoing cost of medical care declines. A recent analysis found that the cost of medical services was about 30 percent lower in the second six months of enrollment than in the first six months.[12] In California, most of the affected families are enrolled in managed care plans. The capitation rates for such plans are based on an assumption that enrollees have relatively long spells of membership. If, instead, Medi-Cal enrollees are cut off soon after the initial period of high medical use, then managed care plans will be serving people who are using services at a higher average rate than expected. This would increase financial losses for the Medi-Cal managed care plans, which would be pressured to either lower payment rates to health care providers or to further limit services for beneficiaries.

Conclusion

California has made substantial progress in its efforts to reduce the number of uninsured Californians. The reinstatement of quarterly reporting could reverse the state's efforts and lead to the loss of coverage by hundreds of thousands of low-income parents and children, most of whom are eligible for benefits. The state's policies would shift back from being in line with most of the nation to becoming one of the most restrictive policies in the country.

California has a serious budgetary problem and the state needs to consider many options — including options to raise revenues — to balance its budget. Care should be taken to avoid actions that prevent eligible parents and children from retaining their health insurance coverage. Even though these are hard times, the state should avoid making conditions even more difficult for its neediest residents.

End Notes:

[1] Other proposals made by the Governor include reducing Medi-Cal provider payment rates, eliminating certain health and medical benefits and lowering Medi-Cal eligibility for low-income parents from 100 percent of the federal poverty line ($15,020 for a family of three) to about 61 percent (about $9,160). This paper discusses only the reinstatement of QSR and does not address the other issues.

[2] Health Care Financing Administration, "Medicaid Welfare Implementation Review: California," issued in 2001. This is the report of a federal review of Medi-Cal operations conducted in 1999 and 2000.

[3] Donna Cohen Ross and Laura Cox, "Enrolling Children and Families in Health Coverage: The Promise of Doing More," Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, June 2002.

[4] Data from the Current Population Surveys of March 2000 and 2001 reveal that about two-thirds of the parents on Medi-Cal are in working families. Families eligible under Section 1931 in California are those who have net incomes below 100 percent of the poverty line ($15,020 per year for family of three), including those who receive CalWorks benefits. Families receiving benefits under Section 1931 are eligible for transitional coverage. The families whose incomes rise above the Section 1931 income limit will predominantly be members of working families. A few may lose Section 1931 eligibility because their family composition changes, but they are the exception, not the norm.

[5] Leighton Ku and Edwin Park, "Improving Transitional Medicaid to Promote Work and Strengthen Health Insurance Coverage," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 29, 2002.

[6] T. Riley, C. Pernice, M. Perry and S. Kannel. Why Eligible Children Lose or Leave SCHIP, Portland, ME: National Academy of State Health Policy, Feb. 2002.

[7] A. Dick, et al. "Consequences of States' Policies for SCHIP Disenrollment," Health Care Financing Review, 23(3): 89-114, Spring 2002,

[8] Health Care Financing Administration, 2001, op cit.

[9] Dick, et al., op cit.

[10] Leighton Ku and Matthew Broaddus, "The Importance of Family-Based Insurance Expansions: New Research Findings about State Health Reforms," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Sept. 5, 2000. Lisa Dubay and Genevieve Kenney, "The Effects of Family Coverage on Children's Health Insurance Coverage," Urban Institute, presentation at the Academy for Health Services Research and Health Policy Conference, Atlanta, June 12, 2001.

[11] Karla Hansen, "Is Insurance Enough? The Link Between Parents' and Children's Health Care Use," Inquiry, 35(3):294-302, 1998. Elizabeth Gifford, Robert Weech-Maldonado and Pamela Farley Short, "Encouraging Preventive Health services for Young Children: The Effect of Expanding Coverage to Parents," Pennsylvania State University, presentation at the Academy for Health Services Research and Health Policy Conference, Atlanta, June 12, 2001.

[12] Ku and Park, op cit.