OMB ESTIMATES INDICATE 400,000 CHILDREN

WILL LOSE

HEALTH INSURANCE DUE TO REDUCTIONS IN SCHIP FUNDING

Use by States of Unspent SCHIP Funds to

Provide Health Insurance

to Unemployed Workers Could Worsen Effects of Funding Reduction

on Children

by Edwin Park

and Matthew Broaddus

Executive Summary

| PDF of this full report HTML of summary PDF of summary If you cannot access the file through the link, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

Starting in fiscal year 2002, federal funding for the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) drops by 26 percent, or more than $1 billion a year. As a result of this funding reduction — which was written into the Balanced Budget Act that established SCHIP in 1997 to ensure the budget was balanced in 2002 under the budget assumptions in use at that time — the number of children insured through SCHIP eventually will fall. The Office of Management and Budget projected in April that while the effects of this funding reduction will be deferred for several years as states use up the unspent SCHIP funds from prior years, national SCHIP enrollment will decline by 400,000 children between 2004 and 2006.

These OMB estimates were made in April using economic projections that assumed no recession. Because the current economic downturn is likely to increase the number of children eligible for and enrolled in SCHIP, however, as families lose their jobs and their health insurance, SCHIP expenditures may rise at a faster pace in the next year or two than had previously been projected. That would leave fewer unspent funds available for states, which could result in an even larger number of children dropped from SCHIP.

On October 4, as part of its economic stimulus package, the Administration stated that states could apply for SCHIP waivers to provide health insurance to unemployed workers. The Administration cited the more than $11 billion in unspent SCHIP funds from previous years as a source of state financing for such coverage of the unemployed. These SCHIP funds, however, are not excess funds. To the contrary, these funds are needed in the next few years to prevent the drop in the number of children that SCHIP covers from growing larger and starting sooner. Given the need for these funds in SCHIP and the likelihood of greater-than-anticipated SCHIP expenditures during the economic downturn — as well as the budget deficits that most states are now facing, which make it difficult for them to contribute the added state matching funds required for states to expand SCHIP to cover the unemployed — it is unlikely that many states will take up the Administration’s offer to use SCHIP funds for unemployed workers. Furthermore, if some states do cover laid-off workers with SCHIP funds, that could make the eventual decline in the number of low-income children that SCHIP insures even larger.

The Problem SCHIP Faces

When Congress created SCHIP in 1997, it provided states with $40 billion over ten years to expand health care coverage for low-income uninsured children but wrote into the law a substantial reduction in the SCHIP funding level for fiscal year 2002 and the two following fiscal years. Congress intended to balance the budget by 2002. To help achieve that goal, the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 — which created SCHIP — provided for a reduction in funding for several programs in 2002, including SCHIP. Without these reductions, the legislation would have fallen short of balancing the budget in 2002, under the economic and budget assumptions in use at that time. SCHIP funding is scheduled to drop by more than $1 billion, or 26 percent, in fiscal year 2002 and to remain at this reduced level through the end of fiscal year 2004.

This funding dip is taking effect at a time that states have an increased need for SCHIP funds. Although many states confronted a series of implementation challenges when they first established their SCHIP programs in the late 1990s and the program got off to a slow start in many areas, enrollment in SCHIP programs has been increasing sharply in the past few years. Federal SCHIP expenditures have increased correspondingly, jumping from $200 million in fiscal year 1998, the program’s first year, to $600 million in fiscal year 1999 and $1.8 billion in fiscal year 2000. In its April 2001 estimates, OMB estimated that SCHIP expenditures would reach $3.4 billion in fiscal year 2002. Moreover, the April OMB estimates did not assume a recession. In a recession, more children will become eligible for SCHIP as their parents lose their jobs and health insurance. The most recent expenditure data indicate that SCHIP expenditures in 2002 are already likely to exceed OMB’s April estimate.

Data and projections from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services indicate how the reduction in SCHIP funding will affect states in the years ahead. These projections show that starting in fiscal year 2004, the level of federal SCHIP expenditures some states will need to sustain their projected SCHIP enrollment will exceed the total federal SCHIP funds available to these states, including unspent funds from prior years and funds reallocated from other states. As a result, these states will have to reduce the number of children they insure through SCHIP or provide additional state funds. The HHS projections also show that the number of states that will face this problem will grow substantially in years after 2004. Our analysis of the HHS data indicates that by fiscal year 2006, projected SCHIP expenditures in nine states will be more than twice the SCHIP funds available in those states. If the affected states are unable (or unwilling) to increase state funding to compensate, they will have no choice but to cut their SCHIP programs.

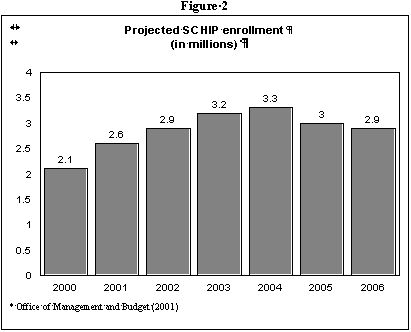

As a result, a large number of children are expected to lose out on coverage. According to the April OMB estimates, the increase in the number of children enrolled in SCHIP programs nationally will slow markedly in 2002 as the effects of the funding reduction begin to be felt, with SCHIP enrollment then nearly leveling off in 2004 and beginning to decline in 2005. OMB projected that SCHIP enrollment will reach 3.3 million in 2004 but fall to three million in fiscal year 2005 and 2.9 million in fiscal year 2006, a decline of 400,000 children in two years. Moreover, the April OMB estimates are likely to understate the decline in SCHIP enrollment. More recent SCHIP expenditure data from HHS indicate that SCHIP expenditures in fiscal year 2002 will be higher than OMB projected in April. In addition, the April estimates assumed no recession; SCHIP enrollment — and hence SCHIP expenditures — are likely to be higher during the downturn than would otherwise be the case. Since expenditures will be higher in the short term than OMB had expected, less in unspent funds will remain, with the result that the eventual drop in enrollment is likely to be larger than 400,000.

Although this decline in national SCHIP enrollment will not appear until fiscal year 2005, children in some states are likely to begin losing out on coverage before then. As noted above, in some states, the SCHIP expenditures necessary to sustain projected enrollment are expected to exceed the available funds starting in 2004, making it likely these states will have to start scaling back their SCHIP programs by that year. The year 2005 is simply the year that an enrollment decline begins to show up in the national estimates. In addition, with a number of states concerned that their future SCHIP costs will outstrip their available funding, some states may take steps much earlier than 2005 — and possibly as early as this year — to halt or slow increases in SCHIP enrollment (and thereby cause fewer children to be insured than would otherwise be the case). Some states are likely to start taking such steps soon to avoid having to reduce the number of children insured through SCHIP in subsequent years.

North Carolina is a case in point. Despite having unspent funds from prior years, North Carolina placed a ceiling in January 2001 on the number of children it would enroll in its SCHIP program, established a waiting list, and stopped enrolling children. The state took these steps because its SCHIP expenditures were projected to exceed its annual SCHIP allotment starting in 2001 and state policymakers became concerned about the prospect of having insufficient federal SCHIP funds in the future. Although unspent SCHIP funds from prior years could ensure that North Carolina had sufficient funds for several years to come, state policymakers were concerned that when the unspent funds were exhausted, the state would have to reduce the number of children served. Since the legislators did not want the state to be in the position of having to cut off currently enrolled children in future years, they decided to limit enrollment now as a way to avoid future enrollment cutbacks. By April 2001, North Carolina had 12,413 uninsured low-income children on its SCHIP waiting list. (This fall, the state increased the enrollment cap in order to enroll the children then on the waiting list.) There is a risk that a number of other states whose SCHIP expenditures exceed their annual allotments will act as North Carolina did and scale back efforts to enroll more uninsured children despite having access to unspent funds from prior years.

The Administration’s Proposal

Against this background, it can be seen that the Administration’s suggestion that states can use unspent SCHIP funds to cover unemployed workers is not likely to result in many such workers gaining coverage. Since states already face a reduction in federal SCHIP funding and many states eventually will have to cut their SCHIP caseloads, states are unlikely to exacerbate these problems by diverting SCHIP funds now for other purposes.

To be sure, some states could conclude they have SCHIP funds that they cannot use and that could be devoted to covering unemployed workers. But such states are likely to be facing budget deficits because of the current economic downturn and to be unable to provide the additional state matching funds that would be needed to draw down more unspent federal SCHIP funds and finance an SCHIP expansion to the unemployed.

Moreover, if some states did extend SCHIP to the unemployed, one result could be an eventual increase in the number of uninsured children nationwide. While a temporary one- or two-year expansion of SCHIP to the unemployed in a few states might not enlarge the magnitude of the eventual decline in the number of children enrolled in SCHIP, longer-term expansions to the unemployed would likely result in many more children ultimately being dropped. Under SCHIP, any funds a state receives that remain unused after three years are reallocated to other states. A number of states rely upon these reallocated monies to fund their programs. If some of the states from which funds are recovered and reallocated were to use their SCHIP funds for unemployed workers, the states receiving the reallocated funds would get less of them. As a result, those states could have to cut back their programs to a greater degree, and the national decline in the number of children served could be larger. New York could be one of the states most adversely affected by such a development because it relies so heavily on the availability of reallocated funds to sustain its SCHIP program.

In short, Congress and the Administration will need to act to shore up SCHIP funding to prevent 400,000 or more children from losing SCHIP coverage starting in fiscal year 2005 (if not sooner because of the economic downturn). They should not be taking steps to aggravate this problem.

States Also Unlikely to Use Medicaid Waivers to Cover Unemployed Workers The Administration has suggested that states use a Medicaid and SCHIP waiver policy that the Administration announced in August as a way to provide health insurance coverage to workers laid-off during the economic downturn. Under this waiver policy, if states cannot (or do not wish to) use unspent SCHIP funds, they can expand coverage to unemployed workers by using savings derived by reducing benefits or imposing increased cost-sharing on current Medicaid beneficiaries. The Medicaid aspect of this policy is not likely to be an effective means of extending coverage to the unemployed. Few states are likely to use it for this purpose (although some states may use the waiver policy to reduce their Medicaid expenditures). The waiver policy provides no additional federal resources to help cover the costs of extending insurance to more beneficiaries. The Bureau of National Affairs recently reported that according to state representatives, "states have been slow to use the new [waiver] initiative because no additional federal money is being offered to help finance coverage expansions."* States currently are undergoing severe fiscal stress. Many states may have difficulty just in providing the level of state resources needed to maintain coverage under their current Medicaid eligibility criteria as growing numbers of children and families meet those criteria and become eligible for the program due to the economic downturn. Expanding Medicaid eligibility criteria to cover more of the unemployed without any additional federal funding is not an appealing course to most states. States likely would have to make painful and politically difficult cuts in Medicaid benefits to secure sufficient savings to finance a meaningful expansion to the unemployed. The Administration’s waiver policy permits states to reduce or eliminate certain health care services that Medicaid covers in order to offset the costs of expanding coverage to groups such as the unemployed. However, 90 percent of the costs that, under the waiver policy, could be reduced by cutting back on covered services are costs for long-term care for frail elderly people and people with disabilities. States seeking to institute such cuts would face major political and possibly legal challenges. It is unlikely that states could produce a sufficient amount of savings in this manner to finance an expansion to the unemployed. States using the Administration’s waiver policy would face rigid budget neutrality rules that could cause them to lose federal funds. States implementing a waiver would be subject to rigid budget-neutrality ceilings. If federal Medicaid costs exceed the ceiling, the state would have to pay the federal government back for the difference. The budget neutrality ceilings are supposed to reflect the level of federal Medicaid costs that would be incurred in a state in the absence of a waiver. But such costs are inherently difficult to predict, since they depend on trends in health care inflation and utilization. The methods that HHS has announced it will use to set budget neutrality ceilings under these waivers are seriously flawed and would place states securing such waivers at considerable risk of losing substantial federal funding. This is another reason that few states are likely to use these waivers to extend Medicaid to the unemployed. For example, in states granted such a waiver, federal Medicaid costs per beneficiary may be limited to the state’s current costs per beneficiary, adjusted only by changes in the national Consumer Price Index for medical care. Yet the CPI for medical care has risen only about half as fast in recent years as actual increases in Medicaid costs per beneficiary (or for that matter, as increases in private health care costs per beneficiary). This is because the CPI for medical care does not capture increases in cost due to changes in the utilization of health care services, technological advances in health care, or changes in the types of services that patients receive. Alternatively, instead of being adjusted by the CPI for medical care, the budget neutrality ceiling for a state seeking a waiver can be adjusted in accordance with federal projections of what the national average increase in Medicaid costs per beneficiary will be in the years the waiver covers. Since these projections reflect the anticipated average rate of increase in cost across states, however, they are likely to understate the rate of increase in Medicaid costs per beneficiary in about half of the states. Finally, states that seek to offset the costs of extending coverage to the unemployed by requiring beneficiaries to pay premiums also would be at risk, since research indicates that increases in premiums lead to declines in enrollment; with the budget-neutrality ceilings set on a per beneficiary basis, states in which enrollment falls as a result of increases in cost sharing would lose federal funds. In short, states that agree to these terms may lock themselves into limits on federal Medicaid funding that prove unrealistically low and cause these states to lose millions of dollars in federal matching funds needed for health care coverage. ___________________ * Jennifer Combs, "Arizona First to Apply for HIFA Waiver; Other States Say No Money for Expansions," BNA Health Care Policy, Oct. 22, 2001. |

One way for Congress to prevent children from being dropped from SCHIP would be to extend the life of certain SCHIP funds that, under the workings of current law, are projected to be returned to the Treasury. Under the law, states that receive unspent SCHIP funds reallocated from other states must return those funds to the U.S. Treasury if they do not use them within a certain period of time, usually one year. Because of a mismatch between the time when unspent funds will be reallocated to states and the time when a number of the states receiving these funds will need them, some states will be unable to use all of the reallocated funds within the required timeframe. As a result, HHS projects that about $3 billion of the $11 billion in unspent SCHIP funds from prior years will be returned to the Treasury by the end of fiscal year 2003. Most of this $3 billion, however, will come from states that subsequently will run out of SCHIP funds and have to begin cutting their programs only a couple of years later. Action by Congress and the Administration to extend the life of these expiring funds and give states affected by the SCHIP funding reduction access to them — so that the funds do not have to be returned to the Treasury and are available when needed in subsequent years — could avert most of the cutbacks that otherwise will occur in the number of children that SCHIP insures.

The remainder of this analysis examines these issues in more detail.

SCHIP Financing and the Reduction in SCHIP Funding

As part of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, Congress established the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) and allocated more than $40 billion in federal funds over ten years to support state efforts to provide health insurance to uninsured children in low-income families. States receive an allotment of federal funds each year to provide low-income children with health insurance coverage. States may use these funds to expand Medicaid, create or expand a separate state child health insurance program, or pursue a combination of both approaches. States must spend some of their own funds as a condition of receiving the federal funds.

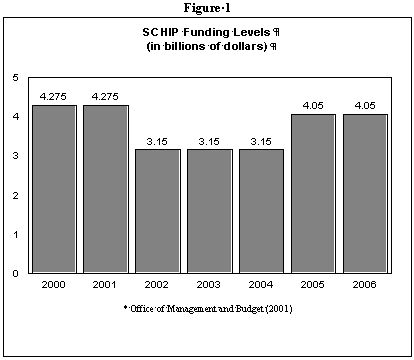

At the time of the Congressional debate in 1997 over how to structure SCHIP, the country was running a substantial budget deficit, and the Congressional Budget Office forecast it would continue to do so each year in the foreseeable future. The legislation in which SCHIP was included, the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, was aimed primarily at reducing the size of these deficits and balancing the federal budget by fiscal year 2002. In response to these budget constraints, Congress adopted an erratic funding pattern for SCHIP. In the first year of the program — fiscal year 1998 — states were allocated $4.2 billion in federal SCHIP funds. Funding for the program remained at about $4.2 billion a year through fiscal year 2001. In fiscal year 2002, however, federal SCHIP funding declines 26 percent to $3.1 billion. Funding for SCHIP is scheduled to remain at a little more than $3 billion a year through fiscal year 2004, after which time it is scheduled to return to more than $4 billion a year. (See Figure 1.) The "dip" in SCHIP funding that begins in fiscal year 2002 was written into law in 1997 solely in response to the desire to produce a balanced budget in 2002 under the budget and economic assumptions in use at the time the legislation was written.

The total amount of SCHIP funds available each year is divided among the states (and territories) according to a formula in the SCHIP statute. States have three years to use the SCHIP allotment they receive for a particular fiscal year. If a state is unable to use its allotment within the three-year period, its unused funds are reallocated to states that did use their full allotment for that fiscal year. (As described below, special rules apply to state allotments for fiscal years 1998 and 1999.)

Thus, a state can use its fiscal year 2001 allotment in fiscal years 2001, 2002, and 2003. At the end of fiscal year 2003, any funds remaining unspent from the state’s fiscal year 2001 allotment will be reallocated to states that did use their full fiscal year 2001 allotment during this three-year timeframe. States receiving reallocated funds have one year to use those funds. Any funds unused after that year revert to the Treasury. The purpose of this reallocation process is to assure that child health funds are distributed efficiently to states that are willing and able to use them to cover uninsured children.

Consequences of the Pending Reduction in SCHIP Funding

OMB estimates included in the Administration’s fiscal year 2002 budget issued in April indicate that OMB expects this reduction in SCHIP funding to cause the number of uninsured children enrolled in SCHIP to decline, beginning in fiscal year 2005. As Figure 2 shows, the OMB estimates show that the number of children insured through SCHIP programs will rise from 2.1 million in fiscal year 2000 to 2.6 million in fiscal year 2001. The rate of growth in SCHIP enrollment is projected to slow in fiscal year 2002, climbing by 300,000 that year and a similar amount in 2003. By 2004, enrollment growth will largely level off, with only 100,000 additional children gaining coverage. Then, according to the OMB estimates, the number of children enrolled in coverage will begin to fall, dropping to three million in fiscal year 2005 and 2.9 million in fiscal year 2006.

These OMB estimates were issued last April. SCHIP expenditure data that have become available since then indicate that OMB’s projection of the level of SCHIP expenditures in fiscal year 2002 is too low. Moreover, the OMB estimates are based on economic projections that assumed no recession would occur. Because the economic downturn is likely to result in an increase in SCHIP enrollment as more families lose their jobs and their health insurance and their children consequently become eligible for SCHIP, enrollment in SCHIP could be higher than projected in the year ahead. The enrollment decline that takes place in subsequent years thus could be larger, or start earlier, than OMB predicted.

The latest data available from the Census Bureau show that the unmet need for SCHIP remains large and that SCHIP should be insuring many more children than the approximately three million whom OMB projects it will serve in the years ahead. As of 2000, the latest year for which these data are available, there were 6.2 million children whose family incomes fell into the range that would make them eligible for SCHIP and who lacked private health insurance coverage. Of these 6.2 million children, 2.6 million were uninsured, while 3.6 million were enrolled in publicly-financed coverage. If states were to enroll 80 percent of these 2.6 million uninsured children in SCHIP, total enrollment in SCHIP would reach 5.7 million children. In light of these data, as well as the fact that the total number of children in the United States is expected to increase in the next few years, SCHIP enrollment should be continuing to rise steadily, rather than tapering off and then declining to 2.9 million in 2006.

The availability of unspent SCHIP funds from the early years of the program appears to be the principal reason that OMB does not anticipate that national enrollment will start to contract until fiscal year 2005. Many states will be able to use unspent funds from prior fiscal years to supplement the reduced SCHIP allotments they will receive starting in fiscal year 2002. States without sufficient unspent funds from previous years may receive unspent funds reallocated from other states. The unspent funds from prior years defer but do not eliminate the problem. The OMB projections indicate that as the unspent funds are depleted, a number of states will move to cut their programs.

Unspent Funds from the Early Years of the Program Only Delay the Effect of the Reduction in SCHIP Funding

All states are now using SCHIP funds to provide health insurance coverage for children. Largely as a result of SCHIP, 38 states and the District of Columbia cover children with incomes up to at least 200 percent of the poverty line. As a result of the expansions in coverage that SCHIP has engendered, as of 1999, nearly 95 percent of all low-income uninsured children with incomes below 200 percent of the poverty line were eligible for health care coverage under Medicaid or SCHIP. Many states have launched child health outreach campaigns to enroll a greater percentage of the eligible children.

Despite this response, however, only 12 states had used all of their first-year SCHIP funds (i.e., their fiscal year 1998 funds) by September 30, 2000, the date by which they had to spend these funds to avoid losing funds to the reallocation process. Many of the other 39 states (38 states and the District of Columbia) reported that it took significantly longer than Congress had anticipated to design and implement their SCHIP programs and to initiate outreach campaigns. Many states initially used a relatively modest amount of their first-year SCHIP funds. Since then, states have gained experience with SCHIP, and enrollment has risen rapidly. Early spending patterns under SCHIP consequently are a poor guide to state need for federal funds in the future (see box on page 11). SCHIP expenditures jumped from $200 million in fiscal year 1998, the program’s first year, to $600 million in fiscal year 1999 and $1.8 billion in fiscal year 2000. In fiscal year 2002, SCHIP expenditures are expected to reach $3.4 billion, according to the April OMB estimates. (Based on more recent state spending projections, HHS projects that SCHIP expenditures in fiscal year 2002 will be $3.6 billion, a figure that may climb still higher as a result of the economic downturn).

In a growing number of states, SCHIP expenditures are beginning to outpace the annual federal SCHIP allotment the state receives. Six states spent an amount on their SCHIP programs in fiscal year 2000 that exceeds the fiscal year 2002 allotment they are likely to receive. Some 27 states are expected to achieve a level of SCHIP expenditures in fiscal year 2002 that exceeds their fiscal year 2002 allotments. (See Table 1.) Rhode Island’s expected SCHIP expenditures this year will be more than five times its fiscal year 2002 allotment. Alaska’s expenditures will be more than four times its SCHIP allotment. Fiscal year 2002 is expected to be the first year that SCHIP expenditures nationally exceed SCHIP allotments for that year.

Texas Experience

Shows States’ Early Spending Patterns in SCHIP Texas offers an example of why early state spending patterns in SCHIP cannot be used as a guide to future state needs for SCHIP funds. At the time of the original September 30, 2000 deadline for use of SCHIP funds for fiscal year 1998, Texas had left 85 percent of its first-year SCHIP funds unspent. That was due largely to the fact that the state did not institute its major SCHIP program until the spring of 2000. Since then, however, SCHIP enrollment has increased rapidly. The number of children in Texas’ SCHIP program jumped from 36,200 in July 2000 to 111,000 in October 2000. The state recently reported that the number of children enrolled in SCHIP in October, 2001 was 443,468. Texas also has seen a corresponding rise in SCHIP expenditures. In fiscal year 1998, Texas used only $1.3 million of its SCHIP funds. In fiscal year 2001, SCHIP expenditures for Texas were expected to rise to $271 million. In fiscal year 2002, they are expected to increase to $455 million. *_______________________ * Personal communication with Randy Fritz, Texas Department of Health, April 24, 2001; Texas Health and Human Services Commission, "Cumulative Application, Enrollment and Eligibility Determination Activity for 10-22-01," October 24, 2001; expenditure data based on state SCHIP expenditures reported to CMS. |

As noted above, the availability of unspent funds from the earlier years of the program delays the effect of the reduction in federal SCHIP funding. In the current fiscal year, states have access to unspent funds from fiscal years 1998-2001, in addition to their fiscal year 2002 allotments. (Although unspent funds from 1998 should have expired — since states initially had only until 2000 to use their allotments of fiscal year 1998 funds and states receiving reallocations of unspent fiscal year 1998 funds had until the end of 2001 to spend them — Congress acted last December to allow states to retain a substantial share of their unspent fiscal year 1998 funds for two additional years, through September 30, 2002. Congress also extended the period during which states can use fiscal year 1999 SCHIP allotments; states now have through September 30, 2002 to use their fiscal year 1999 allotments as well. Unspent funds from 1998 and 1999 not used by the end of fiscal year 2002 expire and must be returned to the Treasury.)

This ability to use unspent fiscal year 1998 and 1999 funds through September 30, 2002 will help soften the effect of the funding reduction during fiscal year 2002. But this provision of law does not eliminate the problems the funding reduction will cause. Only one state, Rhode Island, is projected to have SCHIP expenditures this year that exceed the total of its fiscal year 2002 allotment, its unspent funds from previous years, and funds reallocated to it from other states. Within a few years, however, the level of SCHIP expenditures necessary to sustain projected enrollment will exceed the total amount of funds available in a larger and growing number of states. (See Table 2.)

- By fiscal year 2005, the projected SCHIP expenditures needed to sustain projected enrollment will exceed the total funds available in 12 states — Alaska, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and West Virginia. In three of these states, the federal funds needed to sustain projected enrollment will amount to more than twice the federal funds that will be available. Unless these states come up with additional state funds to cover the shortfall, they will have to cut their programs.

- By 2006, the level of projected SCHIP expenditures needed to sustain projected enrollment will exceed the available SCHIP funds in 15 states — the 12 aforementioned states plus Iowa, Missouri, and Wisconsin. In half of these states, the federal funds needed will be more than twice as large as the federal funds available.

Some of the states that face these funding shortfalls are likely to take steps — perhaps as early as this year — to slow SCHIP enrollment (and thereby cause fewer children to be insured through SCHIP than would otherwise be the case) to avoid large cutbacks in future years. Due to the funding shortfall, the estimates OMB issued in April project that the national increase in SCHIP enrollment will slow significantly starting in fiscal year 2002. Although states that exhaust their SCHIP allotments can shift children into Medicaid, many states may be unable or unwilling to do this; when children move from SCHIP to Medicaid, states must pay 30 percent more of the costs of covering them. In addition, for political reasons, some states may not wish to transfer children to the Medicaid program; some states that have used their SCHIP funds to create new child health insurance programs outside Medicaid did so because of political objections in the state to further Medicaid expansions.

SCHIP Waivers

In July 2000, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services at HHS issued new guidelines regarding the circumstances in which states can seek waivers to use unspent SCHIP funds to insure people other than children, including parents. A number of states have expressed interest in covering parents of children eligible for Medicaid and SCHIP because of the positive enrollment effects on children. According to a growing number of studies based on state experiences, the participation rates of eligible children in Medicaid and other public health insurance programs increase when a state institutes an expansion to cover the parents of these children. One study also found that children are more likely to receive preventive care, such as well-child visits, when both the child and the parent are insured and in public programs.

To date, HHS has approved waivers for Wisconsin, New Jersey, Rhode Island and Minnesota to use unspent SCHIP funds to cover parents. Although such states may use unspent funds from SCHIP’s early years to defray the initial costs of expanding coverage to parents, these states ultimately will be hard-pressed to cope with the reduction in SCHIP funding and to maintain coverage both for SCHIP children and for the parents the states now cover with unused SCHIP funds. By fiscal year 2006, the projected SCHIP expenditures necessary to sustain SCHIP coverage in all four states will exceed the total SCHIP funding available.

On October 4, the Administration suggested that states also could provide health insurance to unemployed workers using unspent SCHIP funds. States were told they could apply for waivers to do this under the Administration’s Health Insurance Flexibility and Accountability (HIFA) initiative. This initiative establishes an expedited approval process for certain types of SCHIP and Medicaid waivers.

It is unlikely, however, that states whose need for federal SCHIP funds is already projected to exceed the federal funds available to them in coming years will wish to increase further their current SCHIP expenditures by using SCHIP funds to expand coverage to the unemployed. Doing so would exacerbate the eventual effects of the SCHIP funding reduction on children’s coverage in these states.

The Administration has said there are a number of states that can undertake sustainable SCHIP expansions for the unemployed because these states otherwise will leave unspent a sizeable share of the SCHIP funds available to them over the next five years. If these states divert SCHIP funds to cover the unemployed for a number of years and thereby increase their SCHIP expenditures, however, that would accelerate — and worsen — the national effects of the SCHIP funding reduction on children’s coverage.

Prompt Action is Needed to Avoid the Adverse Effects of the SCHIP Funding Reduction

Although the OMB estimates indicate that the number of children with SCHIP-funded health insurance will not start declining until fiscal year 2005, it is important that federal policymakers take action soon to address the shortage of SCHIP funding. Some states are likely to begin scaling back their programs before 2005, and a larger number of states are likely to take steps well before then to slow enrollment growth and limit progress in reaching and covering more of the children who are eligible for SCHIP but are unenrolled and uninsured. Policymakers in a number of states are likely to be wary of operating their SCHIP programs at an annual level of expenditure that ultimately necessitates cutbacks.

If Congress does not act to address the problems caused by the reduction in SCHIP funding, a number of states may opt not to implement further child health outreach initiatives. These states may start scaling back their SCHIP programs at the very time the programs need to grow to meet the increased needs for children’s health insurance resulting from the economic downturn. Adding to these problems, some of the states most affected by the SCHIP funding reduction may become increasingly concerned about the level of SCHIP funds they will receive through the reallocation process, since that depends on the amounts that other states leave unspent, and those amounts could decrease as a result of more children becoming eligible for SCHIP during the recession. As a result, the decline in children’s enrollment in SCHIP could start sooner than OMB assumed.

One solution that would help states offset the effects of the SCHIP funding reduction would be to extend the life of SCHIP funds that otherwise are projected to be returned to the Treasury at the end of fiscal years 2002 and 2003 and make these funds available to the states most affected by the SCHIP funding reduction. As noted earlier, states generally have one year to use reallocated funds (with the exception that unspent 1998 and 1999 funds remain available until the end of fiscal year 2002). After the one-year period, states that have received reallocated funds must return to the Treasury any such funds that have not yet been expended. Data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services indicate that $700 million are expected to revert to the Treasury at the end of fiscal year 2002 and $2.3 billion to revert at the end of fiscal year 2003. After 2003, no further funds are expected to be returned.

Some states could extend coverage to the unemployed in the short term by using SCHIP funds that otherwise would revert to the Treasury by the end of fiscal year 2003. If this is done, however, the funds used in this fashion would not remain available to be extended beyond 2003 and be used to avert future cutbacks in children’s enrollment. As noted earlier, the problem here is a mismatch between the time during which these funds will be available for use under current law and the time when states need the funds. For example, all $2.3 billion that is scheduled to expire and be returned to the Treasury at the end of fiscal year 2003 will come from seven states that, in years after that, are projected to have insufficient SCHIP funding and will face a need to cut their programs. If the life of this $3 billion is extended in a manner that targets the states most affected by the SCHIP funding reduction, the eventual SCHIP enrollment decline would be substantially reduced.

Conclusion

OMB estimates show that the Administration expects the number of low-income children who receive health insurance through SCHIP to fall after fiscal year 2004 because of the reduction in SCHIP funding. The OMB estimates highlight the importance of considering the long-term fiscal health of SCHIP and taking prompt steps to avoid the adverse impacts the SCHIP funding reduction otherwise will have. As noted above, the sole reason this funding cut was written into the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 was to show a balanced budget starting in 2002 under the fiscal and economic assumptions in use at that time. There was no policy justification for the reduction.

The proposal to divert SCHIP funds to cover unemployed workers could make this problem worse. Funds are needed to provide coverage to unemployed workers who lose their health insurance when they lose their jobs. Such funds, however, should be provided by the federal government as part of a stimulus package. The funds should not be taken from the SCHIP program.

Finally, Congress should act soon to address the problems that the SCHIP funding reduction will cause for children’s coverage. An important step would be to extend the use of SCHIP funds that are scheduled to expire in the next two years in a manner that targets states affected by the SCHIP funding reduction. Such a measure could moderate substantially the decline in children’s coverage that otherwise will occur.

State |

FY 2002 SCHIP Spending* | FY 2002 SCHIP Allotment** | Spending as Percent of FY 2002 Allotment |

| Alabama | $60,350 | $50,814 | 119% |

| Alaska | $27,910 | $6,589 | 424% |

| Florida | $211,729 | $161,448 | 131% |

| Idaho | $21,045 | $15,187 | 139% |

| Indiana | $78,203 | $44,005 | 178% |

| Iowa | $36,063 | $24,149 | 149% |

| Kansas | $36,992 | $21,508 | 172% |

| Kentucky | $83,468 | $41,011 | 204% |

| Louisiana | $64,028 | $60,129 | 106% |

| Maine | $13,216 | $9,857 | 134% |

| Maryland | $109,491 | $37,699 | 290% |

| Massachusetts | $60,600 | $40,967 | 148% |

| Minnesota | $50,666 | $27,157 | 187% |

| Mississippi | $86,105 | $41,046 | 210% |

| Missouri | $78,551 | $47,991 | 164% |

| Montana | $11,928 | $11,121 | 107% |

| New Jersey | $143,200 | $72,450 | 198% |

| New York | $530,496 | $236,086 | 225% |

| North Carolina | $86,699 | $76,039 | 114% |

| Ohio | $129,973 | $104,261 | 125% |

| Pennsylvania | $115,295 | $101,882 | 113% |

| Rhode Island | $37,739 | $6,819 | 553% |

| South Carolina | $52,924 | $47,354 | 112% |

| South Dakota | $7,788 | $5,995 | 130% |

| Texas | $455,086 | $331,763 | 137% |

| West Virginia | $26,337 | $15,502 | 170% |

| Wisconsin | $62,131 | $36,362 | 171% |

*

Based on state projections of SCHIP expenditures provided to the Centers for Medicare and

Medicaid Services. |

|||

| State | FY2004 | FY2005 | FY2006 |

| Alaska | 125% | 347% | 371% |

| Idaho | 108% | 183% | |

| Indiana | 102% | 171% | |

| Iowa | 145% | ||

| Kansas | 156% | 213% | |

| Kentucky | 111% | 180% | |

| Maryland | 164% | 243% | 262% |

| Minnesota | 131% | 200% | |

| Mississippi | 151% | 205% | |

| Missouri | 125% | ||

| New Jersey | 115% | 200% | |

| New York | 100% | 195% | 211% |

| Rhode Island | 222% | 449% | 485% |

| West Virginia | 147% | 208% | |

| Wisconsin | 121% | ||

| * Projected state SCHIP funding

needs are the federal SCHIP funds necessary to sustain projected enrollment in state SCHIP

programs. They represent the projected federal SCHIP funds that would be used by states

under their SCHIP programs if the states did not face limits on the federal SCHIP funds

available to them. Total available federal SCHIP funds include states’ projected

annual allotments as well as projected unspent funds available to a state from previous

year allotments and/or funds projected to be made available to the state through the

reallocation process. Source: CBPP analysis based on data provided by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. In general, the analysis replicates methodology used in a report published by the Department of Health and Human Services, Report on the Health Insurance Flexibility and Accountability (HIFA) Initiative: State Accessibility to Funding for Coverage Expansions (October 2001). Notable differences between the CBPP analysis and the HHS analysis are the following: a) CBPP uses estimates of states' FY 2002 SCHIP allotments, while HHS has access to the actual figures; and b) CBPP adjusts the amount of available SCHIP funds to reflect unspent funds redistributed through the reallocation process. |

|||