WHAT HAVE WE LEARNED FROM FNS’ NEW RESEARCH FINDINGS ABOUT

OVERCERTIFICATION IN THE SCHOOL MEALS PROGRAMS?

By

Zoё Neuberger and Robert Greenstein

|

PDF of full report |

| If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader |

Overview

The Food and Nutrition Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (FNS) recently released the preliminary results of three new studies. Although none of the studies were nationally representative, taken together the findings lead to four important conclusions that relate to proposals Congress is considering in the context of the reauthorization of the Child Nutrition Programs, particularly proposals to expand the portion of households selected for income verification in the school meals programs:

- Expanded income verification requirements did not decrease the extent to which ineligible children were certified to receive free or reduced-price school meals. FNS’ summary of the research findings states that neither of the expanded income verification policies that were tested “resulted in observable deterrence of erroneous certifications.”[1] While expanded verification did not deter ineligible applications, it did detect some instances in which ineligible households had been certified for free or reduced-price meals and terminated those households’ benefits.

- Expanded income verification requirements led to substantial numbers of eligible low-income children losing the free or reduced-price meals for which their income qualified them. An FNS study of metropolitan areas found that under current verification procedures, children in more than one of every three families selected for income verification in those areas lost their free or reduced-price meal benefits despite being eligible for such meals. For every ineligible child terminated as a result of current verification procedures, at least one eligible child was terminated as well.

- Even under current procedures, substantial numbers of eligible children are not applying for the meals for which they qualify. Nearly one third (31 percent) of the children who were eligible for free meals were not certified for free meals in the school districts studied; of these children, three in every four were not certified even to receive reduced-price meals. (Note: This is a longstanding issue in the school meals programs and does not appear to stem from current verification requirements; it is relevant here because the studies suggest that substantial expansions in verification could aggravate this problem.)

- Some households certified to receive free meals were not eligible for them. More than two-thirds of those households were eligible for reduced-price meals instead.

When a household is approved for free or reduced-price meals but subsequently is found not to be eligible for the meals, one of three factors has caused this situation: 1) the household reported information accurately on its school meals application but the school district mistakenly placed the child in the wrong meal category; 2) the household reported information accurately and was certified correctly at the start of the school year, but the household’s income increased later in the school year and rose over the free or reduced-price income limits; or 3) the household reported information incorrectly on the meals application and was certified on the basis of the erroneous information. Expanded verification is aimed at the third of these three factors; it does not address the other two.

Analysis that combines findings from the various FNS studies indicates that roughly three percent to four percent of the households certified for free meals were not eligible for either free or reduced-price meals — the most serious form of “overcertification” — and were approved to receive free meals because of misreporting of information on a school meals application.

These research findings are of particular significance for policymakers seeking to improve program integrity in the school meals programs. Steps that improve certification accuracy without harming significant numbers of eligible children should be taken. Policy changes also are needed to reduce substantially the proportion of eligible children selected for verification who lose free or reduced-price meals as a result of the verification process.

- School districts should be provided with the resources, technical assistance, and oversight needed to reduce errors by school personnel that lead to children being placed in the wrong meal category. School district personnel who make eligibility determinations should receive more training. In addition, school districts with high administrative error rates should receive more frequent reviews. Districts that repeatedly fail to reduce administrative error to reasonable levels can eventually be asked, after being given time and assistance to make improvements, to return a greater portion of overpayments to the federal government. With the necessary state and federal support, school districts should be able reduce program errors in this manner without bearing an undue administrative burden and without affecting eligible children.

- “Full year eligibility,” as proposed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), should be established so that once a child is determined eligible for free or reduced-price meals, the child remains eligible for the remainder of the school year. Households that correctly report income on the school meals application and are correctly approved for free or reduced-price meals should not be counted as program “errors” if their income happens to rise later in the school year.

- Policy changes are needed to reduce the extent to which the current verification process drives eligible children from the school meals programs. First, as USDA has proposed, school districts should be required to certify automatically for free meals, without the need for an application, children who receive food stamp benefits. (Children certified in this manner are not subject to additional verification, since the food stamp program has already verified their household’s income.) Second, if a family does not respond to an initial request for documents to verify income, the school district should be required to make several attempts to contact the family and explain the verification requirements before terminating a child’s meal benefits. Third, school districts should be encouraged to verify household income by using income data collected by other state agencies before asking families to provide income documentation. This has the potential to allow the eligibility of many low-income children to be confirmed without having to send requests for income documents to those children’s families, and hence to reduce the number of eligible children whose meal benefits are terminated because their families do not respond.

Such measures are designed to reduce both the number of ineligible children certified for free or reduced-price meals and the extent to which eligible low-income children lose access to such meals. Under current verification requirements, an estimated 107,000 eligible children lose free or reduced-price school meals each year because their parents did not respond to an income verification request. Some of these children subsequently reapply and are recertified, after losing the meals for a period of time. However, an estimated 77,000 of these eligible children continue to go without free or reduced-price meals for the remainder of the school year.

Policymakers face a conundrum here. To the extent that the measures just described prove effective in reducing the degree to which eligible children lose free or reduced-price meals as a result of the verification process, the measures will increase program costs. Yet the Congressional budget resolution provides no new funds for the reauthorization of the child nutrition programs. This means that such measures are unlikely to be adopted without a small verification expansion that produces offsetting savings. Yet such an expansion would produce savings because it reduces the number of children — including eligible children — who are certified for free or reduced-price meals

It is possible that a package that combines a very small verification expansion with the measures described above to retain eligible children throughout the verification process would not result in an increase in the number of eligible children who lose free or reduced-price meal benefits as a consequence of verification. Whether that would be the outcome would depend on the effectiveness of the measures to protect eligible children and on keeping any verification increase very small.

Regardless of whether such changes are implemented, USDA should conduct research and rigorous pilot studies to identify measures that are effective in improving certification accuracy without driving substantial numbers of eligible children from the school meals programs, but even these studies would carry some cost that would need to be financed.

Key New Research Findings

1. Expanded Income Verification Requirements Do Not Effectively Deter Ineligible Children from Being Certified for Free or Reduced-Price Meals

In its pilot studies, FNS evaluated the effectiveness of two methods designed to reduce the extent to which ineligible children are certified to receive free or reduced-price meals. One method required every family to provide pay stubs or other income documentation along with the school lunch application. The other approach did not change the current application process, which does not require accompanying documentation of income, but it required most households to provide such documents later in the school year.[2]

FNS then compared the extent to which ineligible children were certified to receive free or reduced-price meals in the districts participating in the pilot studies to similar districts that had not made changes in the application and verification requirements. (Under current verification requirements, generally three percent of approved applications are subject to verification.[3]) FNS found there was no difference between the pilot districts and the comparison districts in the rate at which ineligible children were certified.[4] FNS concluded that neither of the pilot approaches “resulted in observable deterrence of erroneous certifications.”[5] Even requiring every household to provide documentation of its eligibility to receive free or reduced-price meals was found to be ineffective in reducing the extent to which ineligible children were approved to receive such meals.

2.

Income Verification

FNS examined the impact of verification requirements on eligible children in two separate studies — the pilot study of expanded verification requirements discussed in the previous section and a study of the current verification process in seven metropolitan areas.[6] In the areas studied, income verification was found to result in substantial barriers to participation in the school meals programs by eligible low-income children. This finding is consistent with the results of nationally representative studies conducted by FNS in the 1980s.[7]

In the pilot studies under which nearly all households were required to provide income documentation at some point during the school year, the average certification rate among children eligible for free or reduced-price meals (except for those who were “directly certified” on the basis of food stamp or TANF receipt) was 59 percent in the pilot districts, as compared to 71 percent in comparable districts not participating in the study. This finding indicates that expanded verification led to an 18 percent reduction in the extent to which eligible children were approved to receive free or reduced-price meals. (The 18-percent reduction reflects the fact that 59 percent is 18 percent less than 71 percent.)

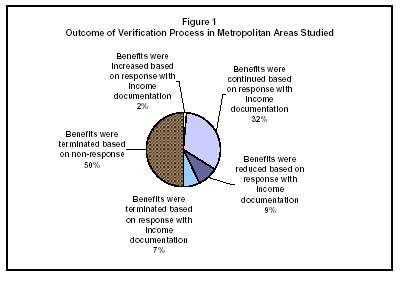

FNS’ study of the verification process in metropolitan areas also found that current verification requirements pose a formidable barrier to program participation by eligible children. In the metropolitan areas studied, half of the households selected for income verification lost their free or reduced-price meals because they did not respond to the verification request, regardless of their eligibility. (See Figure 1.)

This study makes a particularly important contribution to our understanding of the impact of the current verification process because it examined whether children in non-responding households actually were eligible for free or reduced-price meals, based on their income and household size. FNS found that 77 percent of children certified for free meals who were terminated due to failure to respond to a request for verification were, in fact, eligible for either free or reduced-price meals.

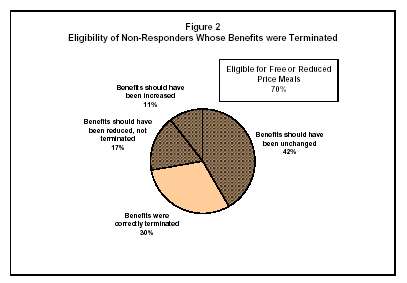

Of all children who were certified either for free or for reduced-price meals but were terminated due to non-response, approximately 70 percent — more than two of every three — were eligible for free or reduced-price meals. (As Figure 2 shows, the 70 percent figure breaks down as follows: 42 percent of those terminated for non-response were eligible for the meals they were receiving; another 11 percent of those terminated for non-response were receiving reduced-price meals but actually were eligible for free meals; and 17 percent of those terminated for non-response were receiving free meals but were eligible for reduced-price meals.) Most of the households whose free or reduced-price meal benefits were terminated as a result of non-response went without such benefits for the remainder of the school year, although FNS found that 25 percent of the households whose meal benefits were terminated due to non-response reapplied — and were approved to resume receiving free or reduced-price meals — at some point in the 10 weeks following the benefit termination.

The study did not examine the eligibility of children terminated for non-response who had been certified on the basis of being “categorically eligible” for free meals — that is, who had been certified by virtue of having provided a food stamp or TANF case number on their school meals application. Categorically eligible households usually do not experience dramatic income increases in a short period of time. As a result, most of the children certified in this manner who subsequently were terminated due to non-response to a verification request likely were still eligible for free meals at the time they were terminated. It therefore is probable that more than 77 percent of the children certified for free meals who lost these meals due to non-response actually were eligible for free or reduced-price meals.

3. Many Eligible Children Are Not Receiving Meal Benefits

The school districts that adopted new verification practices because they were participating in the pilot studies were compared to “comparison districts” that did not make any changes in the application or verification processes. To evaluate the pilot results, FNS gathered extensive information about the operation of the school meals programs in the comparison districts. This information allows for important new analyses regarding both undercertification (children not receiving benefits for which they qualify) and overcertification (children receiving benefits for which they do not qualify). This section of our analysis considers the findings pertaining to undercertification. The following section examines the findings on overcertification.

In the comparison districts, a surprisingly high portion of eligible children were found not to be certified. An average of only 69 percent of children eligible for free meals were certified to receive them; 31 percent of eligible children were not certified for free meals. Approximately eight percent of the children eligible for free meals were instead certified to receive reduced-price meals. But on average, nearly one in four children eligible for free meals — 23 percent — were not certified to receive either free or reduced-price meals.

Lack of certification of eligible households suggests that the program is not reaching a substantial number of low-income households that could benefit from receiving free or reduced-price meals. Such “undercertification” is not the result of income verification requirements. While FNS asked eligible households that did not apply for free or reduced-price meals why they did not apply, FNS has not yet published data on the responses to this question. An earlier study of this matter, however, found a number of reasons why some eligible households do not apply.[8]

The findings on the number of eligible children who are not certified are especially troubling because they pertain to districts that were operating under current program rules. These districts were not implementing expanded income verification requirements. As reported in the previous section of this analysis, expanded income verification requirements led to an 18-percent reduction in the proportion of children eligible for free or reduced-price meals who actually were certified for those meals. It therefore is likely that expanded income verification requirements would push the percentage of children eligible for free meals who actually are certified for those meals significantly below 69 percent.

Lack of participation by eligible children also has implications for the impact of certification inaccuracy on program costs. When ineligible children receive free or reduced-price meals, unwarranted program costs are incurred. Likewise, when eligible children pay for a meal rather than receiving a free or reduced-price meal, program savings accrue. Based on these findings, the program savings that result from eligible children paying for meals may exceed the cost of subsidies provided to ineligible children. If every child were in the correct meal category and ate a typical number of meals for that category, program costs would be higher than they are under the current system.[9]

4. Income Misreporting that Leads to Serious Overcertification Affects Only a Small Fraction of Households

The information gathered about the comparison districts in FNS’ pilot studies, which were operating under current verification procedures, also allows for an important new assessment of the nature and causes of overcertification in the school meals programs.

When combined with other research findings, these data suggest that between three percent and four percent of the children approved to receive free meals are certified incorrectly as a result of the misreporting of income or other information on the school meals application and should be receiving neither free nor reduced-price meals.FNS found that in the districts operating under current law, 18.4 percent of children certified for free meals were not eligible for such meals at the time they were interviewed, which was two to three months after the application process.

FNS also found that more than two-thirds of children who were found to be ineligible for free meals were eligible for reduced-price meals. A little fewer than one-third of the children who were certified to receive free meals but were ineligible for them did not qualify for either free or reduced-price meals at the time they were interviewed. Being certified for free meals despite being ineligible for either free or reduced-price meals is defined here as “serious overcertification.”

There are three factors that contribute to the overcertification FNS found.

- The school district may have incorrectly certified the child even though the household correctly reported its income. In other words, the school district may have mistakenly approved the child for free meals when the information on the application showed the child should be in the reduced-price or the paid meal category. Such errors can occur if the individual making eligibility determinations does not correctly calculate the monthly income for all household members or does not compare the household’s income to the correct eligibility limit for the household size.

- Since interviews were conducted two to three months after certification, the application may have been filled out with correct information and handled correctly by the school district, but the household’s income may have increased (or household size decreased) between the time the application was completed and the time the interview was conducted.

- The household may have misreported its income, whether deliberately or unintentionally. For example, a parent might inadvertently understate income by reporting take-home pay rather than gross earnings or by multiplying weekly earnings by four, rather than 4.3, to obtain monthly earnings.

Each of these types of overcertification is most effectively addressed through a distinct type of policy response. It thus is important to try to ascertain the extent to which each of these factors is responsible for overcertification.

In a separate study, FNS examined administrative practices in 14 school districts.[10] In this study, FNS examined whether children were placed in the correct meal category (free, reduced-price, or paid) based on the income and household size that the household reported on the application or during the income verification process. The results of this study allow for an estimation of the extent to which administrative error contributes to overcertification.

FNS found that nearly six percent of applications were incorrectly certified by school district staff. Specifically, school districts placed 5.7 percent of the approved applications in a meal category that was not the category in which the application should have been placed based on the information the household provided on the application.[11] Some 4.4 percent of approved applications were placed in the free category by school districts when they should have been placed in either the reduced-price or the paid category.[12] The other 1.3 percent of applications that were inaccurately certified by school districts were placed in the reduced-price category when they should have been in the free or paid categories.

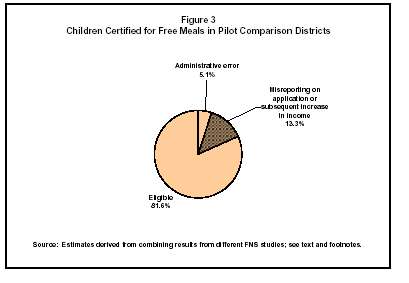

Looking more closely at the 4.4 percent of approved applications that were incorrectly placed in the free-meal category by school district personnel, the FNS data show these applications represented 5.1 percent of all applications approved for free meals.[13] If the districts in the study of administrative practices are comparable to the comparison districts in FNS’ pilot studies, then approximately 5.1 percent of the applications approved for free meals in the comparison districts were incorrectly placed in the free meal category by the school district. The children who were incorrectly placed in the free meal category would account for 5.1 percentage points of the 18.4 percent of children certified for free meals whom the FNS study of the comparison districts found to be ineligible.

This would mean that the remaining 13.3 percent of children certified for free meals who were found ineligible in the FNS study of the comparison districts were incorrectly approved for free meals for either of the other two reasons: either the household misreported income or other information on the school meals application it submitted, or the household’s application was accurate but household size or income changed over the months between submission of the application and the interview that was conducted as part of the FNS study. (See Figure 3.)

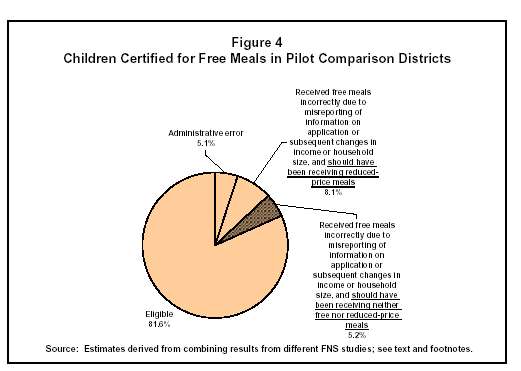

The group of households that were certified for free meals but were ineligible due to either income fluctuation or the misreporting of information on the meals application includes both households that were eligible for reduced-price meals instead of free meals and households that should have been in the paid meal category. Combining findings from FNS’ study of the comparison districts with findings from the study on administrative errors results in an estimate that of the households that received free meals incorrectly for reasons other than administrative error, 61 percent were eligible for reduced-price meals rather than free meals.[14] The other 39 percent of the households that received free meals incorrectly for reasons other than administrative error were eligible for neither free nor reduced-price meals. Since 39 percent of 13.3 percent equals 5.2 percent, this indicates that approximately 5.2 percent of the households approved for free meals were households that should not have been receiving either free or reduced-price meals and that received free meals incorrectly for reasons other than administrative error — that is, because of subsequent increases in household income or because of misreporting of information on a school meals application. (See Figure 4.)

Some portion of the 5.2 percent of households estimated to have been seriously overcertified due to income fluctuation or the misreporting of household information were households that experienced either increases in income or reductions in household size in the months after they submitted their applications, with the changes being large enough to render the households ineligible for free or reduced-price meals. Income can fluctuate significantly if an unemployed parent secures a job or a new mother goes back to work after a period out of the labor force due to the birth of a child. In its study of comparison districts, FNS examined income at the time of the interview and asked households if their income had increased, decreased, or remained constant since they completed their school meals application. FNS has not yet released the results of this aspect of the study, and no information is currently available from the study to indicate how much of this 5.2 percent in serious overcertification resulted from subsequent changes in income or household size and how much resulted from misreporting on the school meals application.

A large body of poverty research shows, however, that families with incomes near the poverty line do experience frequent fluctuations in income. For example, the Census Bureau has found that 24 percent to 27 percent more people are poor in an average month than are poor based on their annual income.[15] In any given month, including the month in which school meals applications are completed, there are some households with incomes below 130 percent or 185 percent of the poverty line whose income later in the school year will be above these levels. Income fluctuation could explain a significant portion of overcertification, including serious overcertification.

In a 1990 study of the income verification process, FNS examined income fluctuations among children certified for free or reduced-price meals.[16] FNS found that among households selected for verification, 14 percent — or one in seven — experienced changes in income or household size by November that were large enough to alter the household’s meal category.[17] Among 1.7 percent of the households examined, the changes in income or household size between submission of the application and November were sufficiently large to move the children from the free-meal category to the paid category.

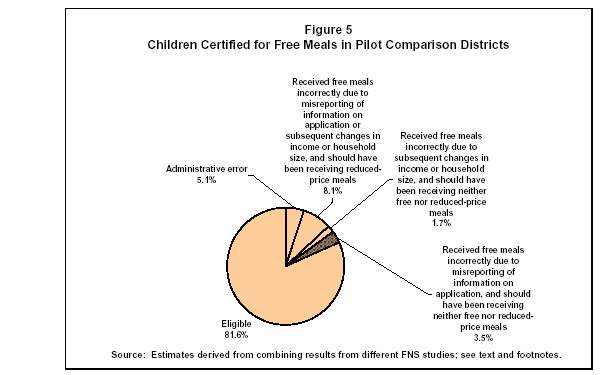

These findings help us distinguish between instances of income fluctuation and instances of misreporting of household information on the application. If income fluctuation is comparable today to what the FNS study conducted in 1990 found, then of the 5.2 percent of households estimated to have been seriously overcertified for reasons other than administrative error, 1.7 percent would have been seriously overcertified as a result of income fluctuation and the remaining 3.5 percent would have been seriously overcertified as a result of income misreporting on the school meals application. This leads to the estimate cited above that approximately three percent to four percent of the households certified for free meals appear to be households that should not be receiving either free or reduced-price meals but were certified erroneously because of misreporting of information by the household on the school meals application. (See Figure 5.)

It is important to bear in mind that this analysis is based on combining results from several studies conducted in different school districts. The analysis would be stronger if all of these data came from a single, nationally representative study. Unfortunately, no such study exists. Taken together, the data from the various studies discussed here offer the best data available on the factors that contribute to the certification of ineligible children.

While this discussion focuses on children certified to receive free meals who should be in the paid category, instances in which children are certified to receive reduced-price meals but should be in the paid category also are cause for concern. The same type of analysis indicates that cases where a household is incorrectly certified for either free or reduced-price meals as a result of the misreporting of information on the school meals application — and should be in the paid category instead — account for approximately eight percent of the overall number of applications approved for either free or reduced-price meals.

If, as a result of misreporting on the school meals application, only about 3.5 percent of households certified for free meals should be in the paid category — and eight percent of households certified for either free or reduced-price meals should be in the paid category — then policy responses to overcertification need to reflect the several different factors that cause overcertification and not focus exclusively on household misreporting.

Implications of FNS’ Research Findings for Policy Proposals

Breaking down the causes of the error rate that FNS found in its study of comparison districts is important because each of the different sources of error is most appropriately addressed through a different policy intervention. There is broad consensus that the appropriate response to findings that some children certified to receive free or reduced-price meals are not eligible for them is to find ways to increase certification accuracy without driving eligible children from the school meals programs. Indeed, the findings which show that under the current verification system, large percentages of low-income children selected for verification end up losing meals for which they qualify should indicate that policymakers need to address that matter as well. In short, there are two issues that need to be addressed: some children are receiving free and reduced price meals for which they are not eligible, and some children who are eligible are losing free and reduced-price meals because of inadequacies in the current verification system.

The proposals that have attracted the most attention as a means of addressing the certification of ineligible children have been proposals to increase the percentage of families required to verify income by producing a pay stub or other form of income documentation. Proposals to increase the proportion of children selected for verification are designed to respond to one of the three causes of overcertification — the submission of applications with incorrect information on them. Expanded verification does not significantly address the other two principal causes of overcertification — administrative error and income fluctuation in months after the application is submitted.

In the discussion below, we first consider ways to reduce error caused by administrative mistakes and income fluctuation. We then discuss issues related to the verification process, proposals to expand verification, and initiatives to reduce the extent to which verification leads to a loss of meal benefits by eligible children.

Administrative Error

Expanded verification does not prevent a school district from mistakenly placing a child in the wrong meal category. While expanded verification might catch some such mistakes after the fact, it also could generate more errors of this sort by school districts. Verification results in new eligibility determinations being made, based on income documentation received through the verification process, and this creates more opportunities for administrative error. FNS’ new study on administrative error found that eight percent of the applications selected for verification were placed in the wrong meal category based on the income documentation received through the verification process.[18] This is a higher error rate than the 5.7 percent of applications found to have been placed in the wrong meal category in the eligibility determinations made at the start of the school year. Available data does not allow for an assessment of whether verification catches more administrative errors than it generates, but expanded verification is clearly not the most effective means of addressing school district errors.

Efforts can be made to reduce erroneous certifications by school districts by promoting sound administrative practices by school personnel and strengthening state and federal oversight. School district personnel who make eligibility determinations should receive more training on how to certify and verify school meals applications accurately. School districts that exhibit signs of high administrative error rates should be subject to more frequent administrative reviews, in combination with targeted training in the areas in which their administrative practices are weak. Finally, districts that repeatedly fail to reduce administrative errors can eventually be asked to return to the federal government a greater portion of overpayments, although not until such districts are given time and assistance to reduce these errors. Together, such steps should reduce administrative error without driving eligible children from the school meals programs.

Errors Resulting from Income Fluctuation

Expanded verification also does not address “errors” that result when a family provides correct information on the school meals application and the school correctly certifies the child, but the family’s income rises later in the year. Since the bulk of the school year — and hence the bulk of the period over which income can increase — occurs after verification is conducted, only a fraction of the instances in which income subsequently rises over the income limits would be detected through verification.

Expanded verification is neither intended nor needed to address such situations. Income fluctuation is better addressed by USDA’s proposal to make full-year eligibility the official policy of the school meals programs.

Under the USDA proposal, once a child is determined eligible for free or reduced-price meals, the child would remain eligible for the duration of the school year. Under current law, households technically are supposed to report income increases of more than $50 a month and schools are supposed to track and act on such changes, but USDA and the states have never enforced this requirement because it is impractical and essentially unenforceable. School districts do not have the capacity to track monthly income fluctuations. Even the Food Stamp Program and Medicaid, with full-time eligibility workers, have moved away from monthly income reporting and allow longer certification periods during which income fluctuations need not be tracked. School district personnel should not be subject to an infeasible requirement to track monthly income changes that has never been implemented or enforced, and then tagged with having committed “errors” if they make accurate eligibility determinations but a household’s income rises later in the school year. The best approach is to concentrate on making sure that certifications are done as accurately as possible at the start of the school year. Those certifications should then last for the duration of the school year.

That the current,

impractical rule that income fluctuations be tracked during the school year

exists only on paper and not in the “real world” is reflected in the

Congressional

The Verification Process

We turn now to issues related to the verification process itself. The issues here are thorny ones. Verification is designed to address cases in which the information provided on the application is incorrect, and verification does lead to the identification of some cases in which incorrect information has resulted in a child being approved for free or reduced-price meals for which the child is not eligible. The new FNS research findings suggest, however, that despite detecting specific cases of error, expanded verification does not reduce the extent to which ineligible children are certified to receive free or reduced-price meals. Moreover, as noted above, verification results in a loss of meal benefits by significant numbers of eligible children and also entails added administrative costs.

In thinking about how to address the problem of some children receiving meal benefits for which they do not qualify, policymakers should focus most on “serious overcertification” — cases where a child receives free or reduced-price meals but qualifies for neither. Cases where a child receives free meals but should be getting reduced-price meals, or vice versa, should not be ignored. But they are not as serious as cases where a child is certified for free or reduced-price meals but is eligible for neither.

If a child who is eligible for reduced-price meals is receiving free meals, USDA pays an additional 40 cents for each lunch. If the child ate lunch every school day throughout the entire school year and was not absent a single day, which is unusual, the overpayment for lunches would amount to $72 over the course of the school year, or between $8 and $9 each month. If the child ate at the average rate — and also ate free school breakfasts at the average rate — the overpayment would amount to $75 over the course of the school year. In some other federal means-tested programs, overpayments of such an amount are disregarded or not categorized as “errors.” In addition, some Members of Congress have expressed interest in providing free school meals to all children with incomes below 185 percent of the poverty line and eliminating the reduce-price meal category altogether. The support for such a proposal, which Congressional Budget Office staff has preliminarily estimated as costing $7.3 billion over ten years if fully implemented throughout the ten-year period, is a further indication that policymakers regard the most serious errors as those in which a child is receiving free or reduced-price meals but is not eligible for either type of meal.

Furthermore, a substantial share of the instances in which a child is certified for free meals but should be receiving reduced-price meals appear to reflect fluctuations in income that have caused a household’s income to rise over the free-meal income limit during the course of the school year. Such “errors” would be eliminated by the USDA proposal to make free and reduced-price meal certifications good for the full school year.

“Serious overcertification” can arise from substantial misreporting of household income, whether deliberate or inadvertent. Verification is designed to detect and deter such misreporting. Verification does, however, have limitations in this regard; it will fail to detect and correct a number of cases in which substantial misreporting of income occurs. It is likely to be especially ineffective in cases in which households have deliberately misreported income by a large amount. This is because households can simply provide documentation for the income they did report, without the school district ever finding out about the income they did not report. For example, a parent with a second job that he or she did not report on the application — or a family that has two earners but listed only one parent’s earnings on the application — can simply provide documentation for the income reported.

It may be noted that if verification were expanded and were effective at identifying all instances of income misreporting among households subject to verification, it still would have only a relatively small effect in reducing serious overcertification. As explained earlier, serious overcertification that occurs because of the provision of incorrect information on school meals applications appears to occur in approximately three percent to four percent of the cases in which children receive free meals. It appears to occur with regard to about eight percent of children who receive either free or reduced-price meals. Suppose verification were expanded very substantially so that 10 percent of free or reduced-price meal applications were subject to verification (more than triple the current percentage). Suppose further that every single instance of serious overcertification caused by income misreporting (in the applications being verified) were caught and corrected as a result of verification — a supposition that clearly overstates what verification can achieve. Even under these circumstances, fewer than one percent of applications would be moved from the free or reduced-price category to the paid category.

This percentage might increase if other policy changes were made in conjunction with expanded verification. But even if the percentage were doubled, which seems unlikely, expanded verification would lead to no more than two percent of applications being moved from the free or reduced-price category to the paid category. This is a small gain for a significant price — the loss from the program of substantial numbers of eligible low-income children.

The Need to

Reduce the Extent to Which Verification

Adversely

Affects Eligible Children

As noted, there are two principal problems related to verification that warrant attention — the problem that some children who do not qualify for either free or reduced-price meals are receiving those meals, and the problem of children who do qualify for such meals losing them as a result of the current verification process. Based on research findings from the various studies, we estimate that for each one percent of meal applications that are subject to verification under current verification procedures, approximately 39,700 eligible low-income children lose access to free or reduced-price meals. Meal benefits for these children are terminated because their families do not respond to a verification request. An estimated 11,000 of these eligible children subsequently reapply and are recertified — and resume receipt of these meals after a period of going without them. The other 28,600 eligible children do not reapply, however, and go for the remainder of the school year without the meal benefits for which they qualify.[20] (See the technical appendix for a more detailed discussion of these estimates.)

With slightly under three percent of school meal applications being subjected to verification, this translates into a total of approximately 107,000 eligible children losing free or reduced-price school meals each year because their parents did not respond to an income verification request.[21] About 30,000 of these children subsequently reapply and resume receipt of these meals after a period of time. The other 77,000 children lose free or reduced-price meal benefits for the full remainder of the school year.[22]

Moreover, the results of the FNS study on verification in metropolitan areas show another result that is equally disturbing: more than one of every three children selected for verification — 35 percent — had benefits terminated despite being eligible for free or reduced-price meals. In fact, for every ineligible child whose benefits were reduced or terminated as a result of verification, at least one eligible child lost school meal benefits for which he or she qualified.

Improvements in the application and verification process to address this situation thus are essential. The estimates just cited of the number of eligible children who lose benefits are based on the current verification procedures. While it is highly unlikely that the verification process could ever be redesigned so as to lead to no eligible children losing free or reduced-price meal benefits, there are important ways in which the process could be improved to reduce the extent to which eligible children lose free or reduced-price meals as a consequence of verification. Three specific steps should be taken to reduce the degree to which income verification drives eligible children from the school meals programs, although the extent to which these policy changes would produce that result is not known.

Expanding direct-certification: Schools districts now have the option of automatically certifying children who are receiving food stamp, TANF, or FDPIR benefits for free meals, a process known as “direct certification.” (FDPIR stands for the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations, a program under which some needy Native American households receive commodities instead of food stamps.) Children who are certified in this manner need not submit a school meals application and are not subject to follow-up verification, since their income already has been verified by the food stamp, TANF, or FDPIR programs. Direct certification has been found to be extremely accurate.[23] It also is less burdensome for schools than processing applications and less burdensome for families. USDA has proposed making direct certification of children who receive food stamp benefits a requirement, rather than an option.

This is an important policy change. It not only should increase the accuracy of meal eligibility determinations but also should reduce the number of eligible children who lose free or reduced-price meals as a result of income verification. Expanding the use of direct certification reduces the number of eligible children who lose benefits because, as just noted, children who are directly certified are not subject to further verification.

In addition to requiring that school districts institute direct certification for children receiving food stamps, pilot programs should be conducted to test direct certification procedures that use participation data from other programs, such as Medicaid. Many children in low-income working families are enrolled in Medicaid but do not receive food stamps or TANF benefits. Enabling participation in Medicaid (and possibly certain other means-tested programs) to be used to directly certify low-income children for free or reduced-price school meals could significantly enlarge the number of low-income children who are directly certified — and thereby further reduce the extent to which eligible children lose benefits in the verification process.

Follow-up when families do not respond: As USDA also has proposed, when a family is selected for verification but does not respond to a verification request, school districts should be required to make several attempts to contact the family and explain the income verification requirements — and the consequences of non-response — before free or reduced-price meal benefits are terminated.

“Direct Verification”: School districts should be encouraged to “directly verify” household eligibility by using data in computerized files maintained by other state agencies, such as the agency that administers the food stamp program or the state employment agency, before asking families to provide income documentation. The advance of computer technology should make such cross-checks feasible for many school districts. To the extent that the income of households selected for verification can be verified in this manner, no request for verification would need to be made to the household.

Under current USDA regulations, districts already have the option to directly verify household income. Few districts use the option, however, which has significant limitations in its current form. This option should be strengthened by enabling school districts to access income data from more programs for these purposes, such as income data in a state’s Medicaid database. In addition, districts should be given incentives to use direct verification.

These steps would

reduce somewhat the number of eligible children who lose access to free or

reduced-price meals as a result of the verification process. The degree to

which such measures will lower the number of eligible children who lose

benefits is not known and needs to be evaluated. (Limited data from a few

school districts that have already implemented more intensive follow-up

efforts with non-responding families indicate that the second of the three

steps just described — follow-up efforts with non-responding families — can

reduce non-response rates but that the reduction that results from this

measure is not dramatic by itself.

A Conundrum

Measures such as those just described to reduce the degree to which eligible children lose benefits through verification face an obstacle, however: such measures increase federal costs. They do so because the federal government is currently securing savings as a result of a substantial number of the eligible children selected for verification losing their free or reduced-price meal benefits as a consequence of the verification process. Addressing this problem — and reducing the degree to which eligible children lose benefits — would cause an increase in federal costs.

The Congressional budget resolution, however, allows no new funds for child nutrition reauthorization legislation. This leads to a conundrum. The only viable way for the Congressional committees that oversee the school meals programs to “pay for” needed reforms to stem verification-induced losses of eligible children from the programs may be to increase the proportion of children subject to verification. Yet by itself that would cause more eligible children to be denied meals. Increasing the proportion of children selected for verification generates savings because some children’s free or reduced-price meal benefits are terminated, and as explained above, a substantial portion of those whose benefits are terminated are eligible for the meals.

Policymakers appear to have two options here. They can make no changes in the current verification process and conduct substantial research and demonstration projects to test ways both to increase certification accuracy and to reduce the adverse effects on eligible children. Even these demonstration projects would cost some money, so a means of financing the research would need to be found.

The other option is to legislate a very small increase in the percentage of children subject to verification and to accompany it with the other measures described here — a requirement for direct certification through the food stamp program (along with pilot-testing of direct certification through Medicaid and other programs), a requirement for robust follow-up efforts when families do not respond to verification requests, and new measures and incentives to make the “direct verification” of children selected for verification a viable approach that can serve as an alternative in as many cases as possible to asking families to supply income verification and terminating their free or reduced-price meal benefits if they do not respond. It is possible that the combined effect of a very small increase in the percentage of children subject to verification and the measures just described to mitigate the effects on eligible children would be to hold the number of eligible children losing benefits to about the same number as under the current verification system. Whether that would be the result would depend on the effectiveness of the measures to protect eligible children and on keeping the increase in verification very small.

Conclusion

The new FNS research examines a number of issues critical to the sound management of the school meal programs. The findings are sobering. Nearly one in every four children eligible for free meals is not certified to receive either free or reduced-price meals. At the same time, a portion of those children who are certified are ineligible. Finally, the expanded income verification procedures that were evaluated were found to be ineffective at improving certification accuracy but drove even more eligible children from the meals programs.

FNS’ research provides important new information about the nature and causes of inaccurate certifications and ought to be taken into account in designing policies to pursue the broadly shared goal of improving certification accuracy without driving eligible children from the programs. Policies should be adopted to reduce certification errors that arise from mistakes by school district personnel. The program also should be made easier to administer by eliminating the antiquated requirement that school districts track monthly income fluctuations. Further research should be conducted to identify means of addressing errors resulting from income misreporting that are both more effective and less harmful than existing income verification procedures.

The most difficult question is what — if anything — to do with regard to the verification system, beyond the new pilot studies and research that are greatly needed. If Congress decides to adopt expanded income verification requirements, any expansions should both be kept very small and be accompanied by policies designed to reduce the degree to which verification causes eligible children to lose benefits, including requirements for direct certification of children receiving food stamps, school-district follow-up with families that do not respond to requests for verification, and the institution of procedures and incentives to enable and encourage school districts to verify eligibility, where feasible, through cross-checks of records maintained by other agencies rather than through verification requests to families.

Technical Appendix

For the 2001-2002 school year, approximately 20 million children were certified for free or reduced-price meals. Of these children, approximately 15 million were in the “pool” from which children were selected for verification. That is, approximately 15 million children were certified for free or reduced-price meals based on paper applications. (The remaining 5 million children were either directly certified or were in schools operating under “Provisions 2 or 3” that were not in their “base year” and thus did not take household applications.[25])

For each one percent of the children in the “pool” who were selected for verification, roughly 150,000 children were selected. Of the children selected, an estimated 37 percent[26] had their free or reduced-price meal benefits terminated due to non-response. This means that for every one percent of children in the pool who were selected for verification, approximately 57,000 children lost their free or reduced-price meal benefits due to non-response. Of these 57,000 children, an estimated 70 percent were eligible for free or reduced-price meals. [27] Thus, each one percent of meal applications that were verified resulted in approximately 39,700 eligible children losing their free or reduced-price meal benefits.

Approximately 28 percent of these children subsequently reapplied and were approved for free or reduced-price meals.[28] Thus, 72 percent of these 39,700 children — or approximately 28,600 eligible low-income children — lost their free or reduced-price meal benefits as a result of non-response and were not subsequently reapproved.

This estimate — that under current verification procedures, approximately 28,600 eligible children lose benefits for the rest of the year for each one percent of children in the pool who are selected for verification — may overstate the extent to which eligible children lose access to meals. School districts sometimes fail to change a child’s meal category when this is supposed to be done as a result of the verification process. In its recent study of administrative practices, FNS found that among households that had been subject to verification, seven percent were in the wrong meal category at the end of the school year as a result of the school district having failed to change the households’ meal category to reflect the results of verification.

In another sense, however, the 28,600 estimate understates the extent to which eligible children lose access to free or reduced-price meals. Eligible children whose free or reduced-price meal benefits are terminated lose access to meals for a period even if they subsequently reapply and are recertified. For each one percent of applications selected for verification, approximately 11,000 eligible children are terminated due to non-response and then are subsequently recertified when they reapply. These children typically lose free or reduced-price meals for some number of days or weeks before reapplying and being recertified.

End Notes:

[1]

NSLP Certification Accuracy Research — Summary of Preliminary

Findings, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition

Service, Office of Analysis, Nutrition and Evaluation, September 12,

2003, page 4, available at

http://www.fns.usda.gov/oane/MENU/Published/CNP/FILES/NSLPCertResearchPolicy.pdf

[2]

More specifically, the two policies that were pilot tested were

“up-front income documentation” and “graduated verification.” In

the up-front income documentation pilot, all applicants for school meals

were required to provide income documentation (or documentation of

receipt of benefits under the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

program, the Food Stamp program, or the Food Distribution Program on

Indian Reservations). In the graduated verification pilot,

districts conducted subsequent rounds of verification if verification

led to a benefit reduction or termination in more than 25 percent of the

applications selected for verification, with the result that some

districts conducted successive rounds of verification until they

verified every application.

[3]

Under current verification requirements, school districts generally

verify either a random sample of 3 percent of approved school meal

applications or a smaller “focused” sample of approved applications that

have income within $100 a month of the free or reduced-price income

limits or that supplied a TANF or Food Stamp case number on the school

meals application in lieu of information on household income.

Because some districts choose to do focused sampling and because no

districts are required to verify more than 3,000 applications, FNS

estimates that under current law, 2.7 percent of all approved

applications are verified.

[4]

Pilot districts were compared to comparison districts as of October 31

of the third school year of the pilot studies. The comparison does not

reflect results of the verification process in the third year of the

pilots. The comparison thus measures the effect of the first two years

of the pilots on the deterrence effect of expanded verification

requirements. It does not measure the extent to which verification

detects specific instances in which ineligible children have been

certified for free or reduced-price meals and leads to a termination of

those certifications.

[5]

NSLP Certification Accuracy Research — Summary of Preliminary

Findings, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition

Service, Office of Analysis, Nutrition and Evaluation, September 12,

2003, page 4, available at

http://www.fns.usda.gov/oane/

MENU/Published/CNP/FILES/NSLPCertResearchPolicy.pdf.

[6]

The preliminary results of both studies are summarized in NSLP

Certification Accuracy Research — Summary of Preliminary Findings,

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of

Analysis, Nutrition and Evaluation,

[7]

See, for example, Study of Income Verification in the National School

Lunch Program, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition

Service, Office of Analysis, Nutrition, and Evaluation, 1990.

[8]

The earlier study found that the principal reasons why eligible

households did not apply were perceived stigma and the quality and

variety of food offered.

[9]

FNS has found that children in the free meal category eat 80 percent of

the time, children in the reduced-price category eat 69 percent of the

time, and children in the paid category eat 48 percent of the time. See

School Nutrition Dietary Assessment Study II Final Report, Report

Number CN-01-SNDAIIFR, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and

Nutrition Service, Office of Analysis, Nutrition and Evaluation, April,

2001, page 15, available at

http://www.fns.usda.gov/oane/MENU/Published/CNP/FILES/sndaII.pdf.

[10]

See School Food Authority Administration of National School Lunch

Program Free and Reduced Price Eligibility Determination, Report

Number CN-03-AV, Paul J. Strasberg, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food

and Nutrition Service, Office of Analysis, Nutrition and Evaluation,

August, 2003, available at

[11]

FNS examined whether applications that were approved for free or

reduced-price meals based on household income were placed in the correct

category. FNS did not examine whether denials of applications were

correct. FNS also did not examine applications approved on the basis of

categorical eligibility as demonstrated by a TANF, Food Stamp, or FDPIR

case number.

[12]

Most of these school district errors resulted in children being placed

in the free meal category who should have been placed in the

reduced-price category. Of the 5.7 percent incorrectly classified, more

than three-fourths were placed in the free meal category when they

should have been in the reduced-price or paid categories. Specifically,

of the 5.7 percent incorrectly certified, 4.1 percent were placed in the

free category when they should have been in the reduced-price category,

0.3 percent were placed in the free category when they should have been

in paid category, 0.5 percent were placed in the reduced-price category

when they should have been in the paid category and 0.9 percent were

placed in the reduced-price category when they should have been in the

free category. See School Food Authority Administration of National

School Lunch Program Free and Reduced Price Eligibility Determination,

Report Number CN-03-AV, Paul J. Strasberg, U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Analysis, Nutrition

and Evaluation, August, 2003, Table 3, available at

http://www.fns.usda.gov/oane/ MENU/

[13]

In the districts FNS studied, 87 percent of children approved for free

or reduced-price meals were approved for free meals and 13 percent were

approved for reduced-price meals. Thus, 4.4 percent of all approved

applications represents 5.1 percent of applications approved for free

meals (0.044 ÷ 0.87 = 0.051).

[14]

FNS found that of the 18.4 percent of children certified for free meals

who were determined to be ineligible for these meals in the comparison

districts, 69.7 percent were eligible for reduced-price meals and 30.3

percent were eligible for neither free nor reduced-price meals. This

means that 12.8 percent of the children certified for free meals were

eligible for reduced-price meals (69.7 percent of 18.4 percent equals

12.8 percent).

Some of these children were in the wrong

meal category because of administrative errors made by school

districts. If the findings from FNS’ study of administrative error are

assumed to apply in the comparison districts, then 4.1 percent of the

applications approved for free- or reduced-price meals — or 4.7 percent

of the applications approved for free meals — were applications

mistakenly placed in the free-meal category rather than the

reduced-price category as a result of administrative error. Since the

study of the comparison districts found that 12.8 percent of the

children certified for free meals were instead eligible for

reduced-price meals (as a result of administrative error, income

increases, or income misreporting), and since the study of

administrative errors found that 4.7 percent of the children certified

for free meals should have been certified for reduced-price meals but

were placed in the wrong category due to administrative error, this

suggests that approximately 8.1 percent of the children certified for

free meals should have been in the reduced-price category and were

incorrectly certified for free meals for reasons other than

administrative error (i.e., because of subsequent increases in household

income or the misreporting of income on the school meals application).

This 8.1 percent of children constitutes 61

percent of the 13.3 percent of children estimated to have received free

meals incorrectly due to either income fluctuation or income

misreporting. (Recall that 5.1 percent of free meal certifications were

incorrect as a result of administrative error. Since 18.4 percent minus

5.1 percent equals 13.3 percent, this indicates that 13.3 percent of the

children receiving free meals were ineligible for reasons other than

administrative error.)

[15]

The Census Bureau computes the “average monthly poverty rate” by first

comparing individuals’ income in each month to the poverty line to

develop an estimate of the number of people that are poor in each month

of a year. The Census Bureau then divides the number of poor people in

each month by the total number of people in each month to derive a

monthly poverty rate. The twelve monthly poverty rates are added

together and divided by twelve to arrive at an average monthly poverty

rate. The average monthly poverty rate was 24 percent higher than the

annual poverty rate in 1996 and it was 27 percent higher than the annual

poverty rate in 1999. See Dynamics of Economic well-Being: Poverty

1996-1999, Report Number P70-91, John Iceland, U.S. Census Bureau,

July 2003, available at

http://www.census.gov/prod/

http://www.fns.usda.gov/oane/ MENU/Published/CNP/FILES/rova.pdf.

[16] See Study of Income Verification in the National School Lunch Program — Final Report, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Analysis and Evaluation, January, 1990, pages 115-117, available at http://www.fns.usda.gov/oane/MENU/Published/CNP/CNP.HTM.

[17] Of the households examined, 8.8 percent experienced income or household size changes by November that were sufficient to move the children from the free meal category to the reduced-price category, while 1.7 percent experienced changes large enough to move the children from the free-meal to the paid category. Among another 2.5 percent of these households, income or household size changes moved the children from the reduced-price meal category to the paid category. Finally, for another 1.1 percent, the income or household size change moved the children from the reduced-price category to the free category.

[18]

See School Food Authority Administration of National School Lunch

Program Free and Reduced Price Eligibility Determination, Report

Number CN-03-AV, Paul J. Strasberg, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food

and Nutrition Service, Office of Analysis, Nutrition and Evaluation,

August, 2003, Table 7, available at

[19]

The Congressional

[20]

It is important to keep in mind that some households receive free meals

even though they are eligible only for reduced-price meals, and thus are

overcertified, but when such a household does not respond to the

verification request, the children lose access to all free or

reduced-price meal benefits and do not receive the reduced-price meals

for which they qualify.

[21]

As explained in footnote 3, FNS estimates that under current law, 2.7

percent of all approved applications are verified. If 39,700

eligible children temporarily lose free or reduced-price meals for each

percentage point of approved children who are selected for verification,

then approximately 107,000 eligible children lose benefits each year

under the current verification process (2.7 * 39,700 = 107,190).

[22]

If 28,600 eligible children lose free or reduced-price meals for each

percentage point of approved children who are selected for verification

and do not reapply, then approximately 77,000 eligible children lose

free or reduced-price meal benefits each year under the current

verification process for the remainder of the school year (2.7 * 28,600

= 77,220).

[23]

In its evaluation of the first year of the pilot projects described

above, FNS found that about 95 percent of children who were directly

certified at the start of the 2000-2001 school year remained eligible

for free or reduced-price meal benefits later in the school year. FNS

concluded that the initial results “provide strong evidence that very

few directly-certified children become income-ineligible later within

the same school year in which they were directly-certified.” See

Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, National

School Lunch Program Application / Verification Pilot Project — Report

on First Year Experience, Report Number CN-03-AV, August, 2002,

Table 6.3 and p.iii. Another study that used Census data found similar

results. See Direct Certification in the National School Lunch

Program — Impacts on Program Access and Integrity, Final Report,

Philip Gleason, Tania Tasse, Kenneth Jackson, and Patricia Nemeth,

Mathematica Policy Research, Inc., U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Economic Research Service, October 2003, Appendix D.

[24]

Overview of

[25]

Calculations based on Table II.2 and II.3 in Direct Certification in

the National School Lunch Program — Impacts on Program Access and

Integrity, Final Report, Philip Gleason, Tania Tasse, Kenneth

Jackson, and Patricia Nemeth, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc., U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, October 2003.

[26]

Data gathered in the preparation of Direct Certification in the

National School Lunch Program — Impacts on Program Access and Integrity,

Final Report, Philip Gleason, Tania Tasse, Kenneth Jackson, and

Patricia Nemeth, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc., U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Economic Research Service, October 2003.

[27]

FNS has conducted three studies in the past 20 years that examined the

eligibility of households that did not respond to a verification

request. In the first study, conducted in the early 1980s, some 86

percent of the non-respondents were eligible for free or reduced-price

meals. See Income Verification Pilot Project Phase II Results of

Quality Assurance Evaluation 1982-83 School Year, U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Analysis and

Evaluation, April, 1984. In the next study, conducted in 1987, some 81

percent of the non-respondents were eligible for free or reduced-price

meals. See Study of Income

Verification in the National School Lunch Program — Final Report,

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of

Analysis and Evaluation, January, 1990, available at

http://www.fns.usda.gov/oane/MENU/Published/CNP/CNP.HTM.

While both of these studies were designed to be nationally

representative, these studies are dated. As discussed on page 6 of this

paper, the most recent study to examine this question found that

approximately 70 percent of children whose free or reduced-price meal

benefits were terminated due to non-response were eligible for free or

reduced-price meals. Because it is consistent with earlier findings and

is more recent, this is the estimate used in this analysis even though

the recent study was not designed to be nationally representative. See

NSLP Certification Accuracy Research — Summary of Preliminary

Findings, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition

Service, Office of Analysis, Nutrition and Evaluation,

[28]

FNS found that among non-respondents who had not moved out of the school

district or dropped out of school, 25 percent reapplied and were

approved for free or reduced-price meals between mid-December and the

beginning of March. Of the 75 percent of non-respondents who did not

reapply for free or reduced-price meals, an estimated two-thirds

were eligible. This group constitutes 72 percent of the eligible

households whose benefits were terminated as a result of non-response to

the verification request. Thus, 28 percent of the eligible children

terminated for non-response subsequently reapplied and were

recertified. Calculations based on data in NSLP Certification

Accuracy Research — Summary of Preliminary Findings, U.S. Department

of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Analysis,

Nutrition and Evaluation,

http://www.fns.usda.gov/oane/MENU/Published/CNP/FILES/rova.pdf