FUNDING HEALTH COVERAGE FOR LOW-INCOME CHILDREN IN WASHINGTON

By

Leighton Ku and

Matthew Broaddus

| PDF of full report |

| If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader |

Summary

The state of Washington has been a trailblazer among the states in developing innovative approaches to expand health insurance coverage, particularly for low-income families and children. The recent economic downturn and resulting shortfalls in state tax revenues have, however, created a harsh fiscal environment in which the state has begun to adopt a variety of cutbacks in Medicaid, SCHIP and Basic Health. Some of these policies will increase the number of people without health insurance and create greater stress on safety net health care providers. Washington has already implemented changes in procedures for enrolling children in Medicaid that will reduce the number of covered children by about 28,000, as estimated by state officials.

The state now plans to impose monthly premiums for low-income families whose children receive Medicaid benefits and to increase monthly premiums for those who receive SCHIP benefits, beginning February 2004, provided that the federal government approves a special waiver.

- The higher premiums would cause about 24,000 low-income Washington children in working families to lose Medicaid or SCHIP coverage.

- A state survey shows there are about 40,000 low-income uninsured children in Washington. The new premiums alone could raise the number of low-income uninsured children in Washington by more than one-half.

- Combined with the procedural changes already implemented, the new policies could more than double the number of low-income uninsured children.

The negative effects of these policies could be avoided, or at least substantially scaled back, by using newly available federal funds that are lowering state outlays:

- $200 million provided by a temporary increase in the Medicaid matching rate passed Congress this spring, as well as another $200 million in general fiscal aid grants,

- about $25 to $26 million, authorized by a new federal law that lets Washington use SCHIP funds to cover the costs of certain children served in Medicaid, and

- $38 million, based on a new policy letting SCHIP cover prenatal care costs for immigrant women.

Together, these funding sources provide more than $250 million in additional federal funding for health care services, as well as another $200 million of general fiscal aid. The state estimates that increasing premiums will lower state expenditures by about $32 million during the 2003 to 2005 biennium. The governor and state legislature could apply these newly available federal funds to avert or reduce the planned increases in children’s premiums. The $25 to $26 million from the new SCHIP legislation alone could cover most of the cost of averting the premium hikes for children, and, thereby, keep tens of thousands of low-income children from losing their health insurance coverage.

Washington’s Tradition of Health Insurance Coverage for Children

In 1987,Washington became one of the first states in the nation expand health insurance for children by adopting new federal options to expand children’s Medicaid income eligibility beyond the traditional income limits based on welfare receipt to higher levels based on a percentage of the poverty line. That same year, Basic Health was created as an innovative pilot program to provide health insurance coverage for low-income state residents who were not covered by Medicaid. In 1993, as part of more comprehensive state health reform legislation, Basic Health was made a permanent program and the Basic Health Plus program was created to provide a more seamless health insurance product for children, coordinating eligibility and coverage with Medicaid for children. In 1994, the state became one of the first states to expand Medicaid eligibility for children up to 200 percent of the poverty line and integrated these higher income eligibility limits with those available under Basic Health. Effectively, children who are members of families enrolled in Basic Health are enrolled in the same plan and receive Medicaid benefits; the state earns federal Medicaid matching funds for the health coverage of these children.

Following the lead of states like Washington that expanded coverage for children, in 1997 Congress enacted the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). Under SCHIP, states receive grants that can be used to finance the expansion of health insurance coverage for low-income children. As an additional incentive to expand coverage, the federal government covers at least 65 percent of total costs of SCHIP programs, a more generous matching rate than the 50 percent or more federal matching rate that applies under Medicaid.[1] A majority of states used SCHIP funds to expand coverage for children up to 200 percent of the federal poverty line ($30,520 for a family of three). Washington, however, already covered children with incomes that high under Medicaid and therefore could not use SCHIP funds to cover children whose incomes were below 200 percent of poverty level because this would not constitute an expansion of coverage, as defined in the SCHIP legislation. In 1999, Washington created a SCHIP program that serves children with incomes between 200 and 250 percent of the poverty line; this new expansion is eligible to use the federal SCHIP funds and earns the enhanced federal matching rate.[2]

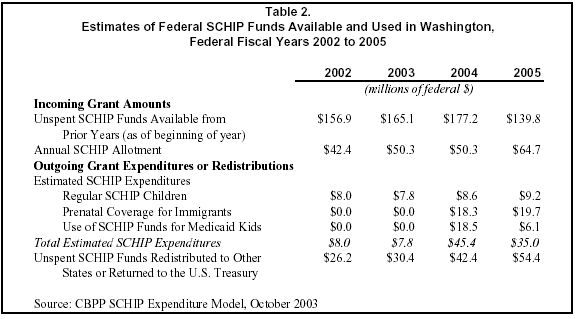

Because Washington has only been able to use SCHIP funds to pay for children in the 200 to 250 percent of poverty range (until the new federal legislation discussed below), Washington has used less of its SCHIP grant than other states. While most states use SCHIP funds to cover uninsured children with incomes between 100 to 200 percent of poverty, Washington uses these funds only to cover uninsured children in the 200 to 250 percent of poverty range. Washington covers fewer children in SCHIP because of the more limited income range and because fewer children are uninsured at this higher income level.[3] As a result, in federal fiscal year 2002, Washington spent $8 million in federal SCHIP funds, compared to a grant allotment of $42 million for that year and a total of about $200 million in federal SCHIP funds available (including unspent funds from prior years).

In September 2003, Washington received federal approval for a new initiative to utilize SCHIP funds for prenatal care for certain women. Washington is using SCHIP funds to provide prenatal care coverage and related health services for low-income women who would not otherwise be eligible for Medicaid or SCHIP. These are essentially low-income immigrant women whose children will be U.S.-born and therefore eligible for Medicaid or SCHIP coverage upon delivery. The state already provided prenatal care to these immigrant women, but used state funds without federal matching support. The new initiative does not expand coverage for women — the state already offered such coverage — but the change in the source of funding lets the state reduce state expenditures by shifting the majority of costs to the federal government and helps the state continue to provide care to this group of pregnant women.

The Plan to Increase Premiums for Children’s Health Insurance

In February 2004, the state plans to implement a controversial policy of imposing monthly premiums for children’s medical care.[4] This plan is contingent upon federal approval of a special waiver, since premiums are not otherwise permissible under federal Medicaid law. The plan would require that families of children on Medicaid with incomes above the poverty line pay monthly premiums of $15 to $20 per child; like other Medicaid beneficiaries these families now do not pay premiums. For children in SCHIP, monthly premiums would more than double from the current $10 per month per child to $25 per month.

Experience from other states (and from Washington’s Basic Health) has shown that increasing premiums can cause many thousands of eligible people to lose health insurance coverage. For example, the state of Maryland recently started charging premiums for children with incomes between 185 and 200 percent of poverty; their initial experience is that half (3,000 of the 6,000 children in that income range) have been disenrolled because of premiums. Last year Oregon increased monthly premiums for its Medicaid program (called Oregon Health Plan Standard). A preliminary state analysis found that within three months, more than 21,000 previously enrolled beneficiaries dropped off the rolls and overall caseload levels fell from 89,000 to 64,000, a reduction of more than one-quarter (29 percent).[5] (More recent data suggest that as many as 32,000 have lost coverage by now.) Thousands of current low-income beneficiaries would drop off because they are unable to pay the monthly premiums. Families may fail to receive notices about the new premiums or lose coverage for protracted periods because they were unable to make the payments for a couple of months. In addition, thousands of other low-income child applicants will be deterred from enrolling by the higher premiums.

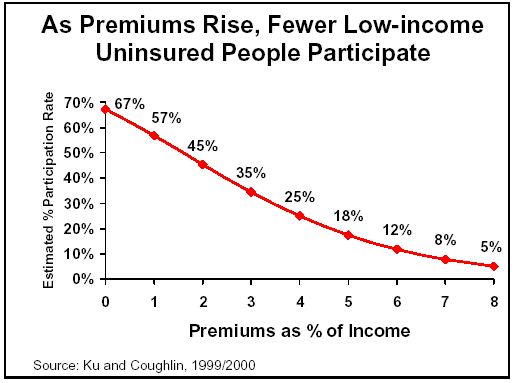

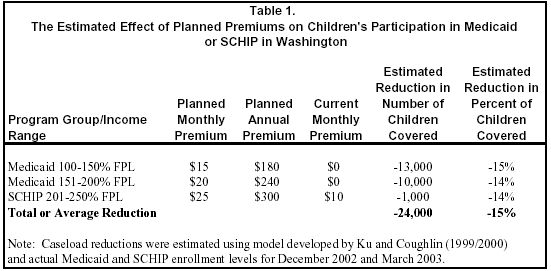

In addition to these recent experiences, research has shown that higher premiums lead to substantial caseload reductions.[6] One study used data from four states (including data from Washington’s Basic Health) to develop a simple econometric model of the relationship between premiums and participation, shown in the figure to the right.[7] Using that study’s model, we estimated the likely effects of the new premiums on participation by children in Washington state, as shown in Table 1.

The planned premiums constitute an average of around one percent of a family’s income per child. A family with two children enrolled would pay about two percent of a family’s income and one with three children would pay about three percent.[8] The state plans to establish a maximum of three percent of family income for Medicaid or SCHIP premiums, regardless of the number of children covered.

Some may believe that almost no families will drop their children’s coverage because of a $15 to $25 premium. It is important to understand that these premiums are high, however, compared to the low incomes of the affected families. A mother with two children trying to make ends meet on $16,000 a year may not be able to find $30 in discretionary income each month to pay for health insurance premiums for her two children. For example, in Washington, rent alone might consume three-fifths of this family’s income, and the remaining income would be needed to meet basic needs for food, clothing, transportation, and so on.[9]

In Washington, the premiums being sought for children in low-income families in Medicaid and SCHIP are often higher than those charged families in the state’s public employees’ health insurance plans, even though public employees generally have higher incomes.[10] For example, one public employee plan charges an additional premium of $15 per month to cover an employee’s children, regardless of the number of children in the family. The majority of public employee plans have child-related premiums of $32 or less per month. For a family with two children, such levels are roughly equivalent to the monthly premium for Medicaid children in the 100 to 150 percent of poverty range and much lower than the premiums for children in Medicaid or SCHIP with incomes above 150 percent of the poverty line. The net effect is that public employees have plans available that let them pay a smaller share of family income for children’s health insurance than plans available for poorer families on Medicaid or SCHIP.

As seen in Table 1, we estimate that the planned premiums would reduce children’s enrollment in Medicaid or SCHIP by about 24,000 children and are equivalent to a 15 percent reduction in enrollment levels. The Washington Caseload Forecast Council estimates that premiums will lower children’s enrollment in Medicaid and SCHIP by about 20,300 by June 2005.[11] While our estimates and the state’s vary slightly, both indicate that a substantial reduction will occur. (Neither our estimate nor the state’s should be viewed as definitive; they are estimates based on the evidence available. The actual impacts will be affected by numerous factors, including the details about how the premiums are implemented.)

The Medical Assistance Administration has already implemented changes in enrollment procedures for children that lower enrollment of children in Medicaid. The state has heightened verification requirements for enrollment, eliminated 12 month continuous eligibility and required a six month status review, and required signatures on new applications. The Caseload Forecast Council estimates these changes will reduce Medicaid child caseloads by about 28,000 by June 2005.

The drop-offs in Medicaid and SCHIP enrollment would substantially increase the number of low-income uninsured Washington children. The 2002 Washington State Population Survey indicates there are about 40,000 uninsured low-income children (in families with incomes below 200 percent of the poverty line).[12] The already-implemented changes in children’s enrollment procedures could cause the number of low-income uninsured children in Washington to rise by as much as 70 percent. The planned premium hikes could cause about 23,000 children with incomes below 200 percent of poverty to lose coverage, increasing the number of uninsured low-income children by another 57 percent. Taken together, these changes could more than double the number of low-income uninsured children in Washington.[13]

New Federal Revenue Has Arrived to Help Pay for Health Coverage

Because of the state’s recent budget shortfalls, the state made serious cuts in Medicaid and SCHIP earlier this year. However, it is also important to note that recent federal policy changes have led to substantial increases in federal revenue that could be used to pay for Medicaid and SCHIP and that reduce the need to erode children’s coverage.

In May 2003, Congress passed legislation that increased federal matching rates for Medicaid, providing Washington with about $200 million in additional federal funds for the period April 2003 through June 2004. This increase is contingent upon states not taking actions to restrict Medicaid eligibility after September 2, 2003. While the children’s premium increase being planned by the state does not appear to violate the letter of the legislation, it is contrary to the intent of trying to protect coverage for low-income populations. The federal law also provided Washington an additional $200 million in fiscal relief grants that may be used for a broad variety of purposes in 2003 and 2004. The federal law that increases the Medicaid matching rate and the additional relief was enacted just as the state legislature was concluding its budget session.

In August, after Washington’s legislative session had concluded, a new federal SCHIP funding law was enacted. This bill helps Washington in various ways. Most important, one provision provides additional federal funding for the costs of covering higher-income children in Medicaid. This provision aids a number of states that — like Washington — expanded Medicaid eligibility for children before SCHIP was enacted and that therefore could not previously use SCHIP funds for the children covered under prior expansions.

Specifically, the provision lets the state use up to one-fifth of its SCHIP funding to cover the expenses for Medicaid children whose incomes exceed 150 percent of poverty. Since the SCHIP matching rate is higher than Medicaid’s, this shift in the source of funding means the state pays a smaller share of the total cost of coverage for these children and the federal government pays more. The financial impact of the bill is not completely clear, but a conservative estimate is that it will bring $25 to $26 million in additional federal revenue and lower Washington’s expenditures by the same amount.[14] This is a temporary bill and covers periods through September 2005. Federal SCHIP funding legislation probably will be amended before that date, but it is too early to know whether this provision (or one like it) will be included in the next SCHIP funding bill.

As mentioned earlier, in September the federal government approved an SCHIP amendment that let the state shift the costs of prenatal care for immigrant women from state-funded programs to SCHIP. The state estimated that this would use about $38 million in additional federal SCHIP funds in 2004 and 2005. Since these costs were earlier being borne by the state alone, this represents about $38 million in savings to the state. When considering the state budget for 2004, the legislature already assumed the state would attain these savings, so these do not constitute “new” funds. In contrast, the provision that lets the state use SCHIP funds to cover Medicaid children was not anticipated by the legislature when this year’s budget was developed, so they are “new” funds that could be used to offset the expected savings due to the higher premiums.

While the state has serious budget problems that cause it to be legitimately concerned about rising Medicaid and SCHIP expenditures, it is also collecting more than $250 million in additional federal revenue for Medicaid and SCHIP (about $200 million from the increased Medicaid matching rate, $38 million from SCHIP coverage of immigrant prenatal care) that could be used to avoid cutbacks to Medicaid or SCHIP and $25 to $26 million from the SCHIP coverage of higher-income Medicaid children. In fact, as will be discussed below, the planned premiums will actually reduce the amount of federal revenue the state will receive to help support its health programs.

The imposition of premiums for children is estimated to lower Washington’s expenditures by about $32 million (state funds only, not including federal matching funds) in the state fiscal 2003 to 2005 biennium. The $25 to $26 million available to Washington from the new federal SCHIP legislation could be applied to prevent all or most of the premium increases.

The Availability of SCHIP Funds

As observed earlier, Washington has historically been unable to use much of its federal SCHIP grant. For example, of the $249 million in total federal SCHIP funds allotted from fiscal year 1998 to 2002, the state only spent $14 million through 2002. (SCHIP funds allotted in one year may be carried over and spent in subsequent years; consequently, some expenditures incurred in 2003 or later years may count against the grant allotments from earlier years.) Because there is such a large amount of unspent SCHIP funding, some of the unspent federal funds — $69 million through the end of 2002 — have been taken from Washington’s grants and redistributed to other states with higher needs (i.e., states that have covered more people using SCHIP funds and therefore spent more of their SCHIP allotments).

To provide a more comprehensive account of SCHIP funding for Washington, Table 2 provides current estimates from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ SCHIP expenditure model.[15] (The amounts shown in the table are federal funds. Since the federal government covers 65 percent of total SCHIP expenditures in Washington, the total (state plus federal) cost is roughly one-half higher than the federal amounts shown and the state’s share of expenditures is roughly one-half lower.)

Two new policies, the use of SCHIP funds for prenatal care of immigrant women and the new federal option to use of SCHIP funds to cover expenditures incurred for higher-income children in Medicaid, will substantially increase Washington’s use of its federal SCHIP grant. As shown, these policies will increase Washington’s federal SCHIP expenditures from about $8 million in 2003 to $45 million in 2004.

The recently enacted federal SCHIP funding bill also let Washington retain about $35.6 million in unspent federal funds that were originally allocated in 1998 and 1999 as well as $26.2 million in unspent funds allocated in 2000. Under the prior law, these unspent funds were scheduled to be taken away from Washington’s accounts, effective September 30, 2002. This policy increases the amount of federal funds available to Washington’s SCHIP program, but if these funds are not spent, they will eventually expire or be allocated to other states.

Washington will continue to have a substantial balance of unspent federal SCHIP funds for the foreseeable future. As a result, if current federal policies are extended, Washington will continue to see tens of millions of dollars taken from its grant each year and redistributed to other states. From an overall federal perspective, this redistribution of unspent funds from low-spending states to high-spending states is efficient and helps to assure that other states do not need to reduce their SCHIP caseloads at times when other states have ample unspent funds. But the policy of redistribution does mean that a substantial amount of federal grant funds are not ultimately used by Washington.

To take better advantage of the federal grant funds and the favorable federal matching rate for SCHIP, the state should be taking steps to further expand SCHIP enrollment and/or benefits, rather than trying to trim SCHIP enrollment. For example, some states that, like Washington, expanded children’s insurance eligibility before SCHIP was enacted have been more effective in using their SCHIP funds by either further expanding children’s eligibility or by using SCHIP funds to cover low-income adults, such as parents of low-income children. Examples include Minnesota, Rhode Island and Wisconsin. Washington earlier planned to use SCHIP funds to cover some additional adults in the Basic Health, but this plan was cancelled due to the state’s budget problems which prevented it from providing additional state funds needed to draw down the SCHIP federal matching funds.

The policy of increasing premiums for SCHIP children will lower enrollment and therefore reduce the state’s SCHIP expenditures, so even more funds will go unspent and will be taken from Washington and redistributed elsewhere.

The Fiscal Inefficiency of Charging Children Premiums

As mentioned above, the use of premiums in SCHIP will further reduce Washington’s ability to use its SCHIP funds and will ultimately increase the amount of federal funds the state will lose. The use of premiums is poor fiscal policy for Washington in other respects as well.

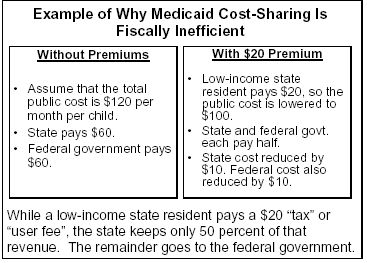

In

general, the use of premiums in Medicaid or SCHIP is equivalent to a

regressive tax or user fee that applies only to low-income beneficiaries.

But unlike other taxes or user fees, such premiums are inefficient because the

state loses half or more of the fee revenue to the federal government, as

illustrated in the box to the right.

In

general, the use of premiums in Medicaid or SCHIP is equivalent to a

regressive tax or user fee that applies only to low-income beneficiaries.

But unlike other taxes or user fees, such premiums are inefficient because the

state loses half or more of the fee revenue to the federal government, as

illustrated in the box to the right.

In this example, based on Medicaid, the state keeps only half of the premium paid by the low-income state resident.[16] In the case of SCHIP, the state would keep just 35 percent of the revenue and the federal government would gain 65 percent. It is difficult to think of another tax or user fee that has such a regressive income distribution, paid only by low-income residents, and that gains so little for the state.

In addition, tens of thousands of children will lose coverage and the federal revenue that would be earned for their Medicaid or SCHIP benefits are also lost to the state. Because most of these children will become uninsured and will depend on state or local safety net providers (such as clinics at Harborview Medical Center or Children’s Hospital, community health centers and so on) for uncompensated care, health care facilities will incur higher uncompensated care costs, for which they cannot earn federal matching funds. The connection between program caseloads and uncompensated care costs has been shown by a study that found when Minnesota expanded public insurance enrollment, uncompensated hospital care costs dipped significantly.[17]

Cutting children’s health insurance coverage also makes it harder for low-income children to obtain preventive and primary health care services that prevent the onset of more serious and expensive health problems. For example, if an asthmatic child cannot get appropriate medications (e.g., inhalers), he or she may experience asthma attacks that end up in a far more costly emergency room visit or hospitalization.

Finally, as noted earlier, one of the new types of federal aid offered to Washington is based on Medicaid expenditures for children with incomes from 150 to 200 percent of poverty. If premiums are not charged for children in Medicaid, the amount of additional federal funds that the state earns because of the new SCHIP legislation could be even higher than the currently estimated $26 million.[18] This is because the state would have higher expenditures for the children in this income range, because of higher participation and because the beneficiaries are not paying the premiums. Because the costs for serving these Medicaid children are higher, the SCHIP matching funds collected could be higher. Thus, eliminating the premiums could raise the amount of federal revenue the state would earn.

Conclusion

At the time when the state legislature considered increasing premiums for children Medicaid and SCHIP, the state was in the midst of a major budget crisis. However, just before the state concluded its budget session, federal fiscal relief was approved and provided about $200 million more in Medicaid funds and an additional $200 million in other fiscal grants. The state is also saving about $38 million by shifting the costs of prenatal care for immigrants to SCHIP. Finally, new SCHIP legislation will provide yet another $25 to $26 million in federal funds to help cover children. The state did not anticipate receiving the $25 to $26 million in additional federal aid at the time it approved the budget for 2004. These funds alone could be used to cover most of the estimated $32 million in savings the state planned for the 2003 to 2005 biennium, so that the state could avoid most or all of the premium increases and resultant caseload reductions.

Given the influx of federal funds that Washington has received in the past few months, it is reasonable to question whether the state really needs to impose premiums for children in Medicaid and increase them for SCHIP children. Our estimates and those of the state indicate that premiums will cause 20,000 to 24,000 low-income children to lose health insurance coverage. The reductions will exacerbate the caseload reductions that have already begun for children in Medicaid because of changes in enrollment procedures. Insofar as the state intends to implement the new premiums in February 2004, there is still time to avert much or all of these negative consequences by using the new federal funds to cancel or postpone the new premiums for children in Medicaid and SCHIP.

End Notes:

[1] The specific matching rate used in SCHIP or Medicaid depends on the per capita income in each state. Poorer states earn higher matching rates, while those with higher incomes receive the 65 and 50 percent matching rates, respectively. Washington has a 50 percent matching rate in Medicaid (temporarily elevated to 52.95 percent because of the fiscal relief legislation) and a 65 percent matching rate in SCHIP.

[2] Eight other states also use SCHIP funds to expand eligibility for children above the level of 200 percent of poverty: California, Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, and Vermont.

[3] According to the Washington State Population Survey, there were fewer than 15,000 uninsured children in families with incomes between 200 and 250 percent of poverty.

[4] State policy also requires certain other low-income persons to pay premiums for their Medicaid coverage. Parents receiving transitional Medicaid coverage are required to pay premiums during their second six months of coverage. Low-income workers with disabilities may buy into Medicaid coverage by paying premiums and an enrollment fee. In addition, children in Basic Health who do not qualify for Medicaid coverage also pay premiums.

[5] News release, “State officials shifting health plan premium grace period by five days,” Oregon Department of Human Services, July 14, 2003.

[6] Leighton Ku, “Charging the Poor More for Health Care: Cost-sharing in Medicaid,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 7, 2003. Julie Hudman and Molly O’Malley, Health Insurance Premiums and Cost-Sharing: Findings from the Research on Low-Income Populations, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, April 2003.

[7] Leighton Ku and Teresa Coughlin, “Sliding-Scale Premium Health Insurance Programs: Four States’ Experiences,” Inquiry 36: 471-480 (Winter 1999-2000).

[8] The total amount of premiums paid by some families could be far higher, if other members of the family must pay Basic Health premiums. In such cases, the family may pay Medicaid premiums for the children as well as Basic Health premiums for other family members. Basic Health premiums are also rising. It is difficult to estimate the total number of families that would have to pay both sets of premiums, but a plausible estimate is roughly 5,000 families. In some cases, families may need to make tough decisions about covering a parent versus covering a child.

[9] The fair market rent in Washington for 2004 is $788 per month, as reported by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. In Seattle, the fair market rent is $923 per month. The fair market rent is set at the 40th percentile of rents in the market area.

[10] Premiums for Washington public employees are 2004 rates from the Public Employees Benefits Board, Washington State Health Care Authority. We estimate the child-related premium as the difference between the premium for the employee and his/her children and the premium for the employee alone.

[11] We do not know the basis for the state estimate. To the best of our knowledge, the model used for our estimates is the most commonly used approach for estimating the impact of premiums on participation.

[12] Data from Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey indicate there were 66,000 low-income uninsured children in Washington in 2002. Most analysts believe the Census data understate the number of Medicaid enrollees and therefore overstate the number of uninsured people. Because of this concern, we present the Washington state survey data.

[13] A small share of those who lose public coverage may be able to purchase or otherwise gain private insurance. But given the size of these reductions compared to the number of children now uninsured, it seems likely that the combined changes would at least double the number of uninsured children in Washington.

[14] The exact amount depends on the interpretation of one provision of this law about the “base” to which the 20 percent ratio applies and also on the Medicaid costs of children with incomes greater than 150 percent of poverty. Among other things, if premiums reduce the number of participating children in this income range, then state expenditures for children in this income range will be lowered, reducing the state savings.

[15] The SCHIP expenditure model provides estimates of federal SCHIP expenditures and amounts available for all the states for a number of years, including actual historical data and future projections. The model is periodically updated to account for new expenditure data or new federal or state policies. Projections of future expenditures for states may differ somewhat from those estimated by the states themselves, because of technical differences in our forecasting methods. We conferred with state officials to estimate some components of expenditures for Washington, but these are the Center’s independent estimates.

[16] In Washington, the state would lose half of the revenue because the federal matching rate for Medicaid is 50 percent. In a state with a higher federal matching rate, the share lost to the federal government would be higher.

[17] Lynn Blewett, "Demonstrating the Link Between Uncompensated Care and Public Program Participation," presented at National Academy of State Health Policy conference, Portland, OR, Aug. 5, 2003. Forthcoming in Medical Care Research and Review.

[18] The state’s estimate of $26 million was based on the assumption that premiums were being charged, both reducing the public cost per child and the number of participating children.