AN

INTRODUCTION TO TANF

By

Martha Coven

|

PDF of full report

Categories: |

| If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

What Is TANF?

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) is a block grant created by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, as part of a federal effort to “end welfare as we know it.” The TANF block grant replaced the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program, which had provided cash welfare to poor families with children since 1935.

Under the TANF structure, the federal government provides a block grant to the states, which use these funds to operate their own programs. States can use TANF dollars in ways designed to meet any of the four purposes set out in federal law, which are to: “(1) provide assistance to needy families so that children may be cared for in their own homes or in the homes of relatives; (2) end the dependence of needy parents on government benefits by promoting job preparation, work, and marriage; (3) prevent and reduce the incidence of out‑of‑wedlock pregnancies and establish annual numerical goals for preventing and reducing the incidence of these pregnancies; and (4) encourage the formation and maintenance of two‑parent families.”

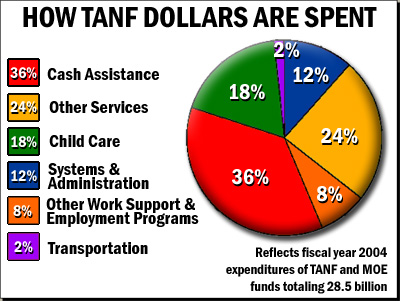

States have used their TANF funds in a variety of ways, including: income assistance (including wage supplements); child care; education and job training; transportation; and a variety of other services to help families make the transition to work. In addition, in order to receive TANF funds, states must spend some of their own dollars on programs for needy families. This is what is known as the “maintenance of effort” (MOE) requirement.

The law that created the TANF block grant authorized funding through the end of federal fiscal year 2002 (September 30, 2002). Since 2002, Congress has been working on legislation to reauthorize the block grant and make some modifications to the rules and funding levels. However, no final agreement has yet been reached on reauthorization legislation. In the meantime, TANF funding has been temporarily extended several times.

Who Is Eligible for TANF-Funded Benefits?

States have broad discretion to determine who will be eligible for various TANF-funded benefits and services. The main federal requirement is that states use the funds to serve families with children. A state can set different eligibility tests for different programs funded by the TANF block grant. For example, a state could choose to limit TANF cash assistance to very poor families, but provide TANF-funded child care or transportation assistance to working families with somewhat higher incomes.

An exception to the broad flexibility that states generally have to establish TANF eligibility rules is that federal law bars states from using federal TANF dollars to assist most legal immigrants until they have been in the U.S. for at least five years. This restriction applies not only to income assistance, but also to TANF-funded work supports and services such as child care, transportation, and job training. A significant percentage of poor children have non-citizen parents who are ineligible for TANF benefits and services. States can use state MOE funds to provide benefits to recent immigrants, but fewer than half do so. Prior to the 1996 welfare law, legal immigrants generally were eligible for benefits, although the income of an immigrant’s sponsor was factored in for the first three years.

Two other key elements of state TANF programs are work requirements and time limits, both of which apply to “basic” assistance (income and other assistance designed to meet basic ongoing needs). Federal law requires that half of the families receiving assistance under TANF must be engaged in some kind of work-related activity for at least 30 hours a week. States get credits for reduced caseloads, however, and are currently effectively required to have much less than half of families engaged in federally-defined work activities. Nonetheless, states have generally exceeded the minimum federal requirements for the number of families participating in work activities.

On time limits, the general rule is that no family may receive federally-funded assistance for longer than five years. States are allowed to use federal TANF dollars to extend time limits, but only so long as no more than 20 percent of the caseload has exhausted the five-year limit. Families receiving assistance funded entirely with state MOE funds are not subject to the federal time limit. While about 20 states have established time limits shorter than five years, states often provide exceptions and exemptions for some groups of families meeting specified criteria.

Not every state was required to comply with all of the federal TANF rules. Several states were, until recently, exempt or partly exempt from TANF requirements because they were operating under a “waiver” already in effect when the 1996 welfare law was enacted. (Prior to the 1996 law, some states had received waivers to change the rules of their AFDC programs.) The rules covered by the waivers and the waiver expiration dates vary by state. (See the table on page 5 for a list of states that had waivers. Only one state still has a waiver in effect — Tennessee, whose waiver is set to expire on June 30, 2007.)

What Level of Funding Does TANF Provide to the States?

Rather than requiring an annual appropriation, the law that created TANF provided for mandatory block grants to the states and territories totaling $16.6 billion each year for six years. This is a flat dollar amount, not adjusted for inflation. As a result, the real value of the block grant has already fallen by nearly 20 percent.

The 1996 law also created supplemental grants for certain states with high population growth or low block grant allocations relative to their needy population, as well as a contingency fund to help states weather a recession.

Finally, the 1996 law created two “performance bonuses.” The first, known as the “high performance bonus,” rewards states for meeting employment-related goals like job entry, job retention, and wage progression. The second is a bonus for reductions in non-marital births, sometimes referred to as the “out-of-wedlock” bonus.

In order to maintain the shared federal-state responsibility that was built into the AFDC program, states must continue spending at least 75 percent of their 1994 contribution to AFDC-related programs. This is the “maintenance of effort” (MOE) requirement, and it totals roughly $10.5 billion.

What Has Been the Experience of TANF Since Its Creation?

TANF cash assistance caseloads fell significantly in the first five years, and overall, the number of single parents who now work has risen markedly. Researchers generally agree that a combination of factors led to reduced caseloads and increased employment rates, including a strong economy, state welfare-to-work efforts, other TANF-related policies, and strengthened work supports — such as the expanded Earned Income Tax Credit, increased availability of child care assistance, and improved child support collections.

Studies of families that stop receiving TANF income assistance show that at any point, about 60 percent of former welfare recipients are employed, while 40 percent are not. Those who work generally earn low wages and often remain poor. In a review of studies of families who left welfare and are working, the Center for Law and Social Policy found that working former recipients tended to earn between $6 and $8.50 per hour.

Many families left welfare not because they found a job, but because they were terminated from the program for failing to comply with requirements, such as the work requirements. Research has shown that many of these families experience barriers to employment that likely impeded their ability to meet the state’s expectations. These barriers include: mental and physical impairments; substance abuse; domestic violence; low literacy or skill levels; learning disabilities; having a child with a disability; and problems with housing, child care, or transportation. Many families with barriers to employment remain in TANF, and one of the challenges in the years ahead will be to help them overcome these barriers so they can succeed in the workforce.

Overall, state TANF programs now provide cash assistance to less than half of the families who meet the eligibility requirements. A recent report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services shows that just 48 percent of families who are poor enough to qualify for TANF cash assistance and who meet the other eligibility requirements receive that assistance. In some cases, families are in deep poverty because the parents are jobless and the family does not receive income assistance — or welfare-to-work services — from state TANF programs.

As cash assistance caseloads fell sharply in the early years of TANF, some federal TANF funds went unspent. As states adjusted to the broader purposes of TANF, they redirected the freed-up resources that previously went to pay cash benefits into programs that provide supports to low-income working families (particularly child care), as well as into welfare-to-work programs. These unspent TANF funds, which states had built up in the first several years of TANF implementation, have dwindled. Data from the Treasury Department shows that states have reduced their overall TANF spending from $19.4 billion in 2003 to $17.4 billion in 2005. The erosion in the purchasing power of these funds due to inflation will make the impact even more severe.

As states have been forced to scale back their use of TANF funds, they have made cuts in a number of programs, including child care subsidies for low-income working families and programs designed to help parents move from welfare to work. Unless Congress provides substantial new TANF or child care resources in reauthorization legislation, states will have little choice but to make further cuts in their programs in the years ahead, as inflation continues to erode the value of these funding sources.

The impact of time limits, another key element of the 1996 law, is still unclear. Families are only now starting to reach their federal time limit, and states with shorter time limits have granted a variety of extensions and exemptions. In many states, a large share of the families affected by the time limits were working families who had been receiving cash assistance to supplement their low earnings.

Finally, the 1996 welfare law also included as goals reducing non-marital pregnancies and encouraging the formation of two-parent families. Teen pregnancy and non-marital birth rates did fall in the 1990s, and the proportion of low-income children living in two-parent families rose. It is unclear how much, if at all, TANF policies affected these trends.

|

Alabama |

FA (Family Assistance Program) |

|

Alaska |

ATAP (Alaska Temporary Assistance Program) |

|

Arizona** |

EMPOWER (Employing and Moving People Off Welfare and Encouraging Responsibility) |

|

Arkansas |

TEA (Transitional Employment Assistance) |

|

California |

CALWORKS (California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids) |

|

Colorado |

Colorado Works |

|

Connecticut |

JOBS FIRST |

|

Delaware** |

ABC (A Better Chance) |

|

D.C. |

TANF |

|

Florida |

Welfare Transition Program |

|

Georgia |

TANF |

|

Guam |

TANF |

|

Hawaii** |

TANF |

|

Idaho |

Temporary Assistance for Families in Idaho |

|

Illinois |

TANF |

|

Indiana** |

TANF, cash assistance; IMPACT (Indiana Manpower Placement and Comprehensive Training),TANF work program |

|

Iowa |

FIP (Family Investment Program) |

|

Kansas** |

Kansas Works |

|

Kentucky |

K TAP (Kentucky Transitional Assistance Program) |

|

Louisiana |

FITAP (Family Independence Temporary Assistance Program), cash assistance; FIND Work (Family Independence Work Program), TANF work program |

|

Maine |

TANF work program |

|

Maryland |

FIP (Family Investment Program) |

|

Massachusetts** |

TAFDC (Transitional Aid to Families with Dependent Children), cash assistance; ESP (Employment Services Program), TANF work program |

|

Michigan |

FIP (Family Independence Program) |

|

Minnesota** |

MFIP (Minnesota Family Investment Program) |

|

Mississippi |

TANF |

|

Missouri |

Beyond Welfare |

|

Montana** |

FAIM (Families Achieving Independence in Montana) |

|

Nebraska** |

Employment First |

|

Nevada |

TANF |

|

New Hampshire** |

FAP (Family Assistance Program), financial aid for work exempt families; NHEP (New Hampshire Employment Program), financial aid for work mandated families |

|

New Jersey |

WFNJ (Work First New Jersey) |

|

New Mexico |

NM Works |

|

New York |

FA (Family Assistance Program) |

|

North Carolina |

Work First |

|

North Dakota |

TEEM (Training, Employment, Education Management) |

|

Ohio** |

OWF (Ohio Works First) |

|

Oklahoma |

TANF |

|

Oregon** |

JOBS (Job Opportunities and Basic Skills Program) |

|

Pennsylvania |

Pennsylvania TANF |

|

Puerto Rico |

TANF |

|

Rhode Island |

FIP (Family Independence Program) |

|

South Carolina** |

Family Independence |

|

South Dakota |

TANF |

|

Tennessee* |

Families First |

|

Texas** |

Texas Works (Department of Human Services), cash assistance; Choices (Texas Workforce Commission), TANF work program |

|

Utah |

FEP (Family Employment Program) |

|

Vermont |

ANFC (Aid to Needy Families with Children), cash assistance; Reach Up, TANF work program |

|

Virgin Islands |

FIP (Family Improvement Program) |

|

Virginia** |

VIEW (Virginia Initiative for Employment, Not Welfare) |

|

Washington |

WorkFirst |

|

West Virginia |

West Virginia Works |

|

Wisconsin |

W 2 (Wisconsin Works) |

|

Wyoming |

POWER (Personal Opportunities With Employment Responsibility) |

|

|

|

|

* State currently operating under a waiver from the federal TANF rules. |

|

|

** State had a TANF waiver that has since expired. |

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

|