A POINT-BY-POINT

RESPONSE TO HERITAGE FOUNDATION CLAIMS

ABOUT FEDERAL SPENDING

| PDF of

analysis Is Domestic Spending Exploding? An Assessment of Claims by the Heritage Foundation and Others |

|

| If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

Over the past few weeks, the

Heritage Foundation and other conservative organizations have made claims

about recent trends in federal spending in general and domestic spending in

particular. Below are brief analyses of some of the most prominent claims,

as well as of the related notion that domestic spending increases are the

main reason why large deficits have emerged in recent years (see box). For

more details, see the related Center analysis, “Is Domestic Spending

Exploding? An Analysis of Claims by the Heritage Foundation and Others,”

revised

Claim: Federal spending has risen so much that it exceeds $20,000 per household for the first time since World War II.

This statement creates the impression that federal spending is exploding. It is not.

The Congressional

In fiscal year 2003, federal spending equaled 19.9 percent of the Gross Domestic Product, the basic measure of the size of the economy. This was lower than in every year from 1975 through 1996.

|

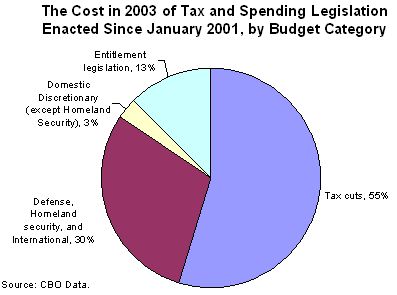

What Caused the Swing from Surpluses to Deficits? The Heritage reports imply that huge increases in federal spending in general and domestic spending in particular are the primary cause of the historic swing since 2001 from surpluses to deficits. This is incorrect. The adjacent chart, based on CBO data, shows that the cost of the tax cuts enacted since the start of 2001 significantly exceeds the costs of all defense, anti-terrorism, and domestic discretionary and entitlement increases combined. Tax cuts were responsible for 55 percent of the cost in 2003 of legislation enacted since January 2001, a percentage that will rise still higher in the years ahead.

|

Spending has indeed risen in the past few years. Spending virtually always rises faster during economic slumps, as more people lose their jobs and qualify for unemployment insurance and other benefits. But at 19.9 percent of GDP in 2003 (and 20.0 percent of GDP in 2004, according to the latest CBO projections), it is well below its levels in the downturns of both the early 1980s and early 1990s, when spending exceeded 22 percent of GDP in most years.

The Heritage reports overlook these basic facts about federal spending levels and trends, focusing instead on increases in real federal expenditures per household. Analysts who are not ideologically motivated generally do not use expenditures-per-household to track changes in spending over extended periods of time, since doing so can produce misleading results.

Real federal spending per household necessarily

rises over time. One reason for this is advances in technology, such as

advances in health care technology that improve health but raise health

care costs. Another reason is increases in real wages in the

Claim: Federal spending unrelated to defense and the terrorist attacks grew 11 percent between 2001 and 2003, the fastest rate of growth in nearly a decade.

As noted, recessions virtually always trigger a temporary increase in the rate of growth of domestic spending, as more workers lose their jobs and qualify for programs such as unemployment insurance. It thus should come as no surprise that domestic spending grew more quickly during the recent downturn than during the preceding economic boom or that the rate of spending growth in recent years was the fastest in nearly a decade. After all, the previous economic downturn occurred about a decade before the current one.

The more important question is whether domestic spending grew more quickly during the recent downturn than during the previous downturn, in the early 1990s. It did not. Domestic spending outside homeland security grew at about the same rate in the past few years as during the downturn of the early 1990s. In addition, total federal spending is substantially lower now as a share of the economy than during the previous economic slumps.

Claim: Appropriations for discretionary (i.e., non-entitlement) programs grew 31.5 percent between fiscal years 2001 and 2003, which shows that spending is out of control.

Those who cite this figure rarely explain that

this growth is due primarily to extremely large increases in funding for

defense, homeland security, and international affairs (which includes the

costs of our extensive post-war operations in

Moreover, most of the increases in funding for domestic programs outside homeland security came in appropriations bills for fiscal year 2002, which were written in 2001 at a time when policymakers believed larger surpluses remained. Once the surpluses disappeared, the growth of funding for domestic discretionary programs outside homeland security slowed sharply to 1.8 percent per year after adjusting for inflation. This is less than one-third its rate in 2002.

Claim: The majority of the new spending since 2001 is unrelated to defense or terrorism.

The Heritage reports trumpet a claim that increases in domestic spending have exceeded the increases in defense and anti-terrorism spending. Heritage produces this result by bypassing the standard method for measuring increases in spending caused by policymakers’ actions. To get its numbers, Heritage includes not only the cost of legislation passed by policymakers but also temporary cost increases that occur automatically when the economy weakens (such as a rise in unemployment insurance costs) and other increases in costs that are beyond policymakers’ control, such as increases in health care costs that affect the private and public sectors alike.

Congressional Budget Office data show that a substantial majority of the increase in spending in 2003 that resulted from legislation enacted since January 2001 — 63 percent of the increase — occurred in the defense, homeland security, and international affairs areas.

Claim: The omnibus appropriations bill (and the other fiscal year 2004 appropriations bills) are sufficiently bloated that discretionary spending will jump another 9 percent in 2004.

Outlays (i.e. actual spending, as opposed to the funding that the appropriations bills provide) will indeed rise by 8.8 percent between fiscal years 2003 and 2004, without adjusting for inflation. Outlays will rise 7.0 percent, after adjusting for inflation.

But the bulk of this increase in spending is not the result of the 2004 appropriations bills. Rather, it results from funding that was appropriated by Congress in prior years and was already “in the pipeline,” such as the additional funding for operations in Iraq that Congress approved last spring and ongoing expenditures to rebuild New York City from the 9/11 attacks, made from funds that Congress provided in 2002. It is incorrect to regard the fiscal year 2004 appropriations bills as the cause of the increase.

The 2004 appropriations bills increase total appropriations for all discretionary programs — including both defense and domestic programs — by 3.4 percent before inflation, and 1.7 percent after adjusting for inflation. Most of this increase is in defense, homeland security, and international affairs. The increase in appropriations for domestic discretionary programs outside homeland security in fiscal year 2004 is 1.0 percent, after adjusting for inflation.